Suz and I have an old friend with a longstanding habit of beginning sentences with the words “I don’t want to say that…”, followed by a less than laudatory suggestion about another person. For example, “I don’t want to say that he’s unreliable…” or “I don’t want to say that she’s lying…” These sentences tend to trail off, the “but” unspoken but implied, and the rest of the sentence left to the listener’s imagination.

The effect is uncalculated: Our friend is no Mark Antony, intentionally and artfully creating the desired effect by emphasizing her pretended wish to do the opposite.1 Yet the effect is unmistakable, and all the more for her ingenuousness. Clearly she does in some way want to say something like that, or why would she mention it at all?

Many people, of course, do this sort of thing quite intentionally; it is a rhetorical move with a long pedigree. As a person who likes putting words to things, I am pleased to note that this move has a name—several names, in fact!

My Latin scholar friends, thinking perhaps of a classic example in Cicero, or, for that matter, of Mark Antony’s well-known speech in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar,2 tend to call it praeteritio or preterition (etymologically, “to pass over”). In general English discourse, a pair of Greek-derived terms may be more common: One is paralipsis, with a similar etymological origin; the other, which I much prefer, is apophasis (“to say no”).

One reason for my preference is that “apophatic” is an important term in theology, a term I use regularly anyway, making it easier to remember.3 Apophatic theology is theology by negation—most fundamentally, approaching the idea of God by stating what he is not.4 The opposite term for positive language about God is cataphatic, from Greek cataphasis (“affirmation”). Very useful and necessary terms in theology!5

If you want another Latin-derived synonym, apophasis/paralipsis/preterition6 is also called occupatio. Not, I suppose, that we need two Latin words and two Greek words for the same rhetorical move—however useful any one such word may be. Far be it from me, though, to impose my preference on you! Now that you have all the facts, pick the one you like best!7

Given the topic at hand, I should perhaps state explicitly that this observation is entirely sincere and non-ironic!

Written, of course, in Early Modern English, Shakespeare’s language—but representing what Mark Antony would have said in Latin, if he had really said it.

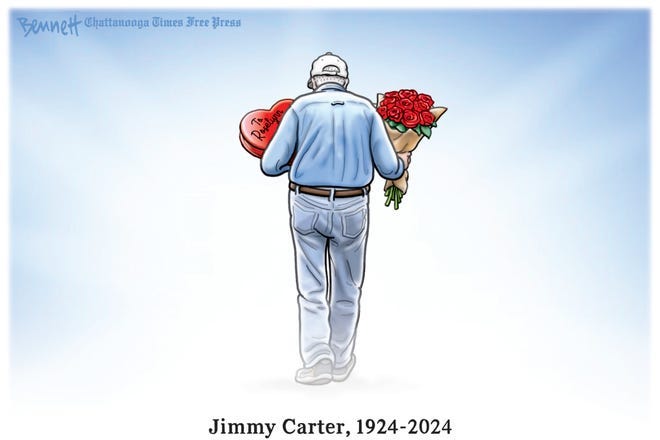

Most recently I used apophatic in my last post, a longread on heavenly obituary cartoons, describing the restraint of Clay Bennett’s tribute to Jimmy Carter, a variation on the common “heavenly reunion” theme of such cartoons. This effort is apophatic in its restrained silence about the nature of heavenly reunion, and specifically its avoidance of the metaphorical tropes common in such cartoons (the pearly gates; St. Peter at his lectern; and of course loved ones rushing into each other’s arms). Which usage is, of course, what occasioned this post! (And yes, not to leave it implicit, I will affirm, categorically and cataphatically, that in this footnote I am inviting you to check out that piece if you haven’t yet read it!)

For example, words like “infinite” and “immortal” are negations: God is not finite, not mortal.

One reason apophatic (negative) language is important in theology is that cataphatic (positive) theology is always analogical—approaching God by way of analogy to known things that are always different from what God is. For example, to say that God is omnipotent is a positive, cataphatic statement: God is all-powerful. But what do we mean by “power”? The power of God is not the kind of power produced by an engine or by a star, nor is it legal or political power. Every kind of power we know is obviously different from the divine attribute we call “power.” We might say that God’s power is the ability to act to produce effects. But what do we mean by “act”? We know what effects are, and we can ascribe certain effects to God, but what God’s action means we do not know, or at least we know only by analogy to the kind of actions we can do or see in other agents. Whatever positive, cataphatic statements we make about God—that he is good, that he is love, etc.—always turn on analogy; the only non-analogical—or univocal—statements we can make about God are negative, apophatic. Which means that what is not known about God is greater than what is known!

For what it’s worth, preterition also has a theological meaning—though a much more limited one, entirely unrelated to its rhetorical meaning, and, compared to apophasis, not very useful to me. In rhetoric, preterition refers to topics that are (usually very conspicuously) “passed over”; in Reformed (Calvinist) theology—the tradition in which I was first raised, long before my conversion to Catholicism—preterition refers to God “passing over” those whom he has not predestined to salvation, i.e., allowing them to be damned. (On that disturbing topic, see again my last piece on heavenly obituary cartoons, specifically note 2, where I briefly discuss trends in thinking about heaven and hell, including trends in Catholic soteriology in the direction of the vast majority of all humanity, or even all of humanity, being saved. I expect I will have more to say about that at some point…)

Try not to forget apophatic, though, since that’s the one you may see here from time to time!

Orthodox are so into apophatic! I’ll always have a lot of the East in me. One of the things I loathed about Calvinism is that they seem to have God in a box. In outline form. And, of course, they are always right, on the smallest details of those outlines.

"So-crates: 'The only true wisdom consists in knowing that you know nothing.'"

"That's us, dude!"

Sorry, I know your post is serious, but I couldn't help myself. That was one of the movies that I was raised on and it does have a Catholic saint in it.

In all seriousness though, the #1 thing that I hope you write someday (no pressure) is your spiritual journey to the Catholic faith. I just love reading conversion stories. I realize that's a daunting challenge that would probably take up a book, but hey, if Scott Hahn can do it, so can you. (By the way, I never read Scott Hahn's book but I hear it's really good.)