Heavenly obituary cartoons and Jimmy Carter tributes, ranked

[LONGREAD: Obituary cartoons as “reverse icons”—or the real thing]

Let’s face it: As popular a theme as the pearly gates1 of heaven and St. Peter at his lectern may be in obituary editorial cartoons, they’ve generally been overdone to the point of exhaustion, besides being often sentimental and sometimes perfunctory. That doesn’t mean they can’t still be good! It does mean that finding a worthwhile approach to this familiar subject isn’t easy on a cartoonist.

At best, such heavenly obituary cartoons reflect the human and social impulse to speak and think as well as possible of the recently deceased: an impulse rooted partly in compassion for the grieving as well as human solidarity in the face of mortality. Their popularity also reflects, of course, the popular modern tendency (a complex tendency with disparate roots)2 to suppose that (almost?) everyone goes to heaven.3

Such cartoons may sometimes carry, for the devout, a theologically queasy air, not only in their universalist tendency, but also in how they depict the departed arriving in heaven—for example, with “Let’s get this party started” energy, as if heaven hadn’t been quite ready for prime time until now. In most cases, though, obituary cartoons are less a statement of any kind about heaven than a metaphorical commentary about the person’s earthly legacy.

Obituary cartoons as “reverse icons”

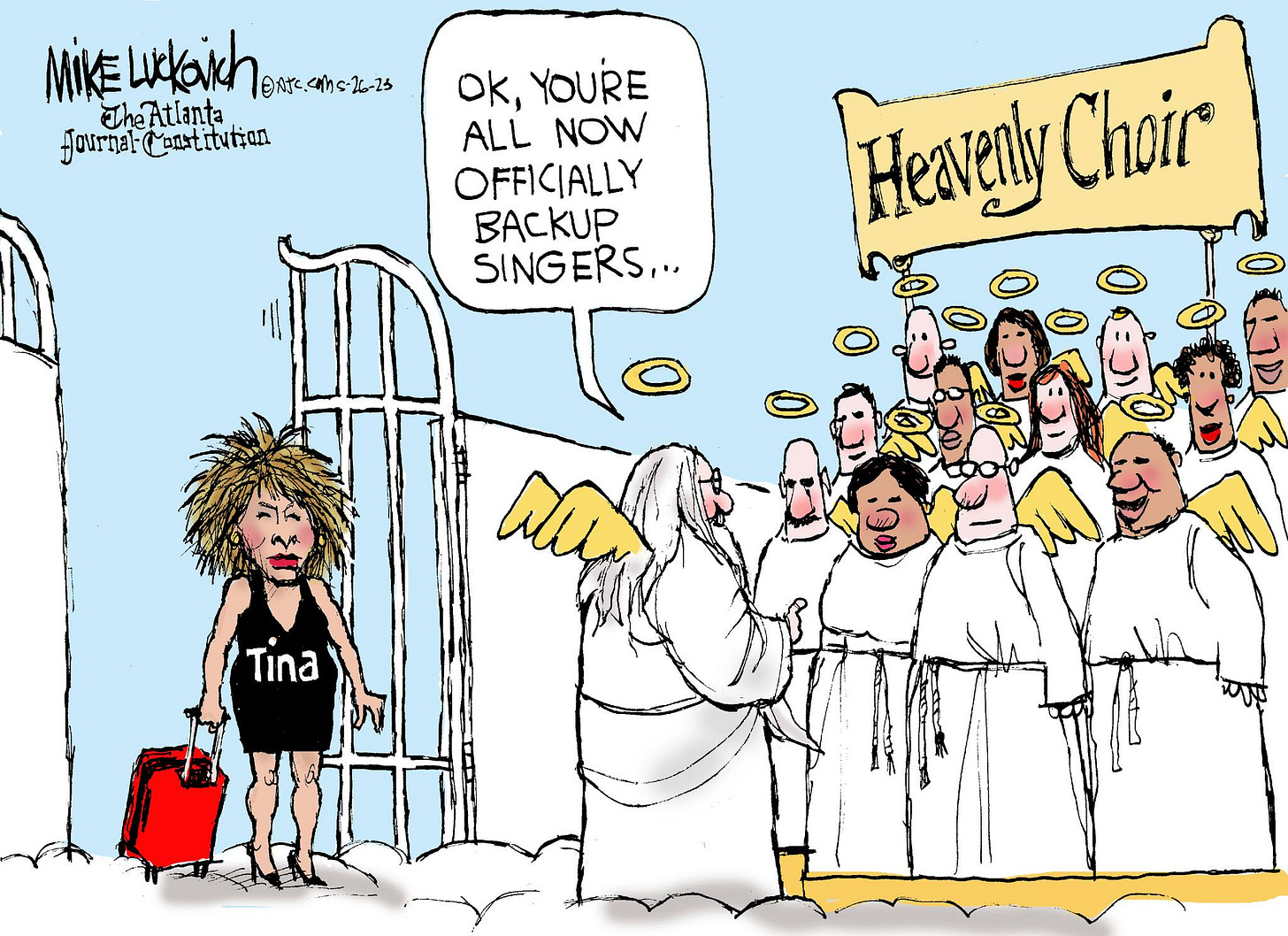

Atlanta Journal-Constitution cartoonist Mike Luckovich has in his time done a number of variations on the pearly-gates theme, and in this exploration I’ll be relying on his work as an organizing principle. To lay the groundwork, let’s consider Luckovich’s tribute to Tina Turner, who died in 2023. (I know I promised Jimmy Carter cartoons in the headline … I’m getting to it!)

What is the message of this cartoon? Let’s start with what it isn’t: The message is not that Turner’s immortal soul is now in heaven (much less that her pipes—which, of course, she left behind on earth!—are now the highlight of celebration in heaven).

To be sure, we might reasonably suppose that Luckovich, to whatever extent he may credit the idea of heaven at all, is conscious of no glaring reason to fear that Turner wouldn’t make the grade. On the other hand, we can also guess that Luckovich probably wouldn’t want to be thought to imply in this cartoon that Buddhists like Turner (Turner adhered to Nichiren Buddhism for the last half-century of her life) “go to heaven” when they die—an account of what awaits after death contrary to Buddhist beliefs!4

The actual message is, I think, pretty straightforward and intuitive: in a word, “Tina Turner is the GOAT.”5 But I’m writing an analytical inquiry, not simply appealing to intuition! Why and how is the cartoon saying this?

To answer this question, we need to address the cartoon in what I’m going to call iconic terms. Cartooning as an art form tends to be, in a specific sense, highly iconic, and I’m going to argue that there is a very particular sense in which this kind of obituary cartoon tends to function as what I call a reverse icon. Let’s look at the iconic first.

The word “icon” means, of course, one thing in Christian sacred art, but it also has a range of secular meanings. (This is not inherently a corruption or desecration of sacred vocabulary; like the Greek word eikon, the late Latin word icon means simply “image” or “likeness”—and even includes statues, which are generally not classified as “icons” in the sacred sense by English-speaking Christians!6) In one secular sense of the word, we may say that Turner is “an icon.” In another sense, to say that cartooning is iconic means that this art form depends heavily on a familar visual vocabulary of conventions, symbols, and pictorial shorthand, from the stylization and abstraction of the imagery to word balloons and motion lines, among countless other examples.7

Look again at the Turner cartoon above. Almost everything in the image (the fluffy clouds underfoot, the white robes and golden wings and halos, the white wall and wrought-iron gate) serves an iconic or conventional function: It’s all an instantly recognizable vocabulary clearly saying “cartoon heaven.” But how does this heavenly iconography function editorially? This is where we get to obituary cartoons as reverse icons—in the specifically Christian sense of “icon.”

“Windows into heaven” is a common way of expressing how religious icons are held to function in the Christian iconographic tradition—despite the fact that the actual subjects are typically drawn from earthly scenes in the Bible or sacred tradition. The idea is that visible, earthly subject matter is rendered in a sacred style that (to those who are properly disposed, seeing with the eyes of faith) conveys or reveals invisible, divine realities.

What obituary cartoons like this do is, of course, the opposite of this! Drawing on the iconography of “heaven” in popular imagination and pop culture (especially in other cartoons), such cartoons depict heavenly scenes as metaphors for earthly realities. Specifically, cartoon heaven in these cartoons functions in two ways:

First, it represents the fact of the public person’s passing. (Had you seen the Turner cartoon before hearing about her death, that would have been your immediate takeaway: that she had died. Incidentally, Turner’s carry-on case is also iconic: It identifies her as a new arrival, i.e., recently departed from earth.)

Second, it tends to place the departed person among the honored dead—or, at least, it addresses the cartoon primarily to those who hold that person in some kind of honor (the main target audience, after all, for most obituary cartoons).8

In this case, notably, the honor is not for Turner’s moral virtue or religious piety, but for the cultural impact of her music; heavenly honor is here symbolic of earthly achievement. This reverse-icon dynamic is, I think, the norm for heavenly obituary cartoons. After all, editorial cartoonists editorialize; editorials are not homilies, and editorialists are not theologians. All things being equal, to seek religious insight—or for that matter to diagnose religious error—in your average editorial cartoon seems to me a failure less of theological literacy than of cartoon literacy.9

Of course, things are not always equal, and not every editorial cartoon is your average editorial cartoon! It is possible for a heavenly obituary cartoon to rise above reverse iconography? To make a genuinely transcendent statement? To serve, in fact, as a true icon?

Three types of heavenly obituary cartoons: A Luckovich triptych

To explore this question, I will consider three classes of heavenly obituary cartoons, all with President Carter as their subject. Helpfully illustrating the three classes is a triptych of Jimmy Carter obituary cartoons by Luckovich.10 (On X-Twitter Luckovich mentioned “going back and forth” on these cartoons. I have a clear favorite, but let’s not jump the gun.)

Approach #1: Heavenly reunion

One popular class of obituary cartoons focuses on the idea of heavenly reunions with loved ones who have gone before.11 Luckovich offers one of this sort reuniting Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter:

This approach is cartoon editorializing at its most obvious and sentimental.12 In lieu of saying much about Jimmy, except, of course, that he loved his wife of 77 years and that she loved him,13 it leans on the emotional power of the specter of separation from one’s beloved spouse and the hope of reunion.

Is this a transcendent statement? From a Christian perspective, we must acknowledge that the idea of heaven as reunion with loved ones is not well founded in scripture, and all our mental images of reunion are supplied with earthly furnishings that cannot realistically be applied to the life to come.14 Such cartoons may be taken in the spirit of the idea of the afterlife as wish fulfillment, as our idea of happiness on our own earthly terms.

It is possible, though, to view these cartoons as a metaphorical expression of the divine and therefore eternal character of love. Love reveals the truth that the beloved is unrepeatable and of incomparable worth; in love the voice of God echoes, whispering that death is not the end. The doctrine of the communion of saints promises that, however transformed and unimaginable our relations in eternity may be, we are not separated forever from those who have died in God’s love. Viewed in this spirit, these cartoons may have real iconic power.15

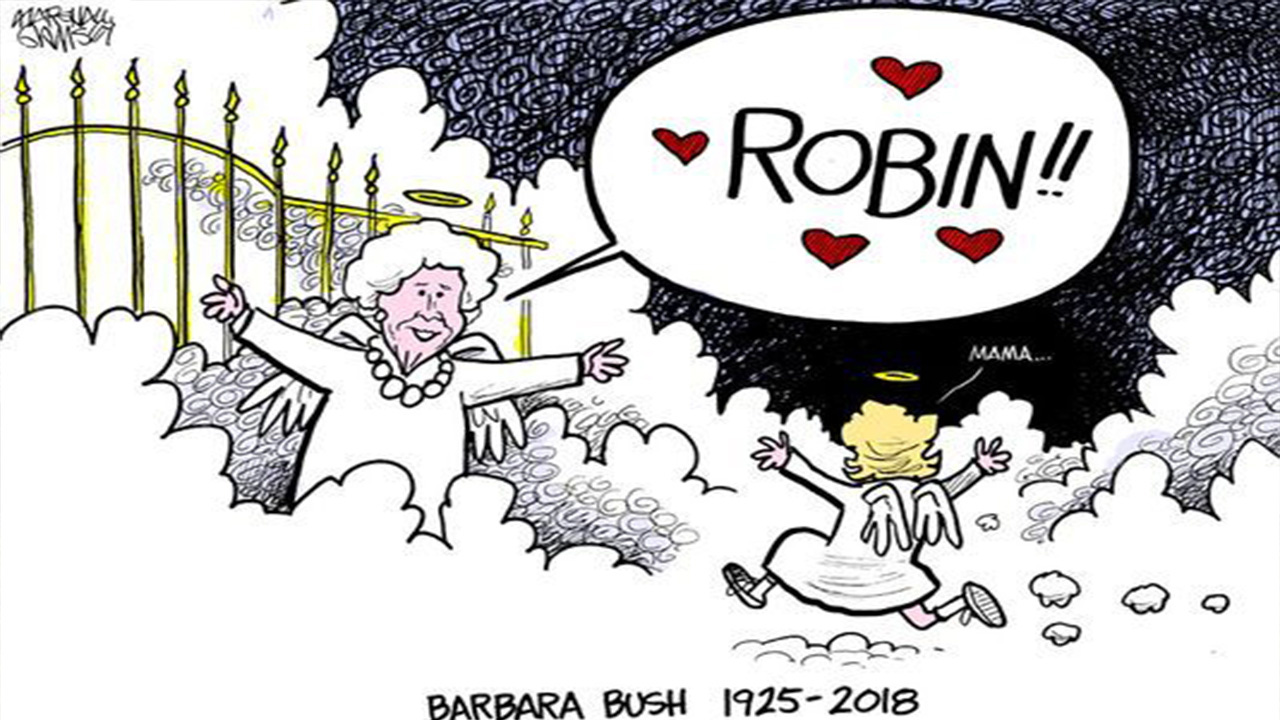

The main problem with this approach, from an editorial perspective, is that it’s so ready-made that conceptually identical approaches are bound to be taken by multiple cartoonists. Here’s one from Marshall Ramsay for Mississippi Today:16

I’m not saying that both versions aren’t moving. Once you’ve seen this idea done a few times, though, diminishing returns start to kick in, and you hope for something fresher.

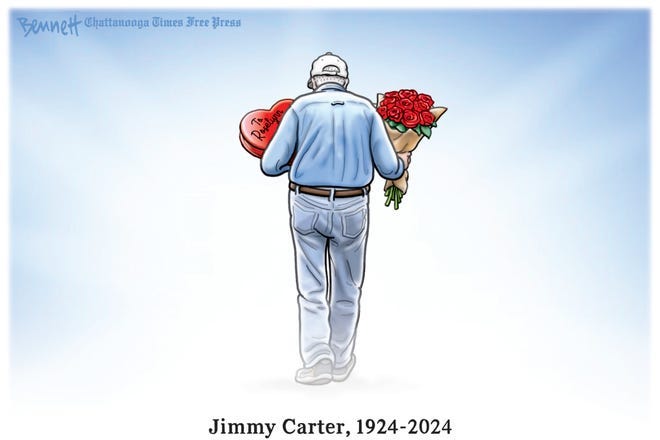

For what it’s worth, here’s a more restrained, symbolically rarefied interpretation of the same idea by Clay Bennett for the Chattanooga Times Free Press:

I find this version powerful in its lowkey apophaticism:17 It tells us something about Jimmy’s heart as he shuffles off this mortal coil, leaving the hope of reunion to our hearts and imaginations.

Returning to the pearly gates, John Darkow (Columbia Missourian / CTNewsJunkie), memorializing Rosalynn Carter in 2023, has a nice variation on this theme:

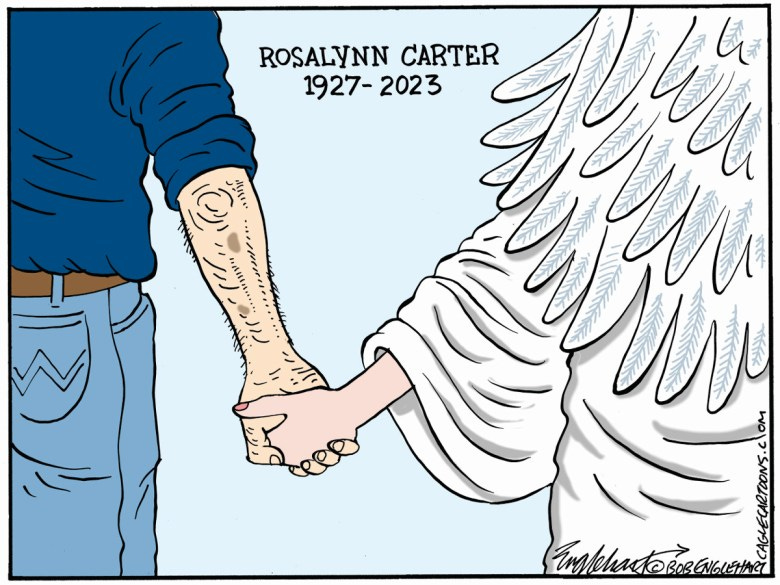

Finally, here’s another one for Rosalynn by Bob Englehart (PoliticalCartoons.com / CTNewsJunkie) movingly suggesting that the Carters were never separated at all.18

Approach #2: Heavenly occupation

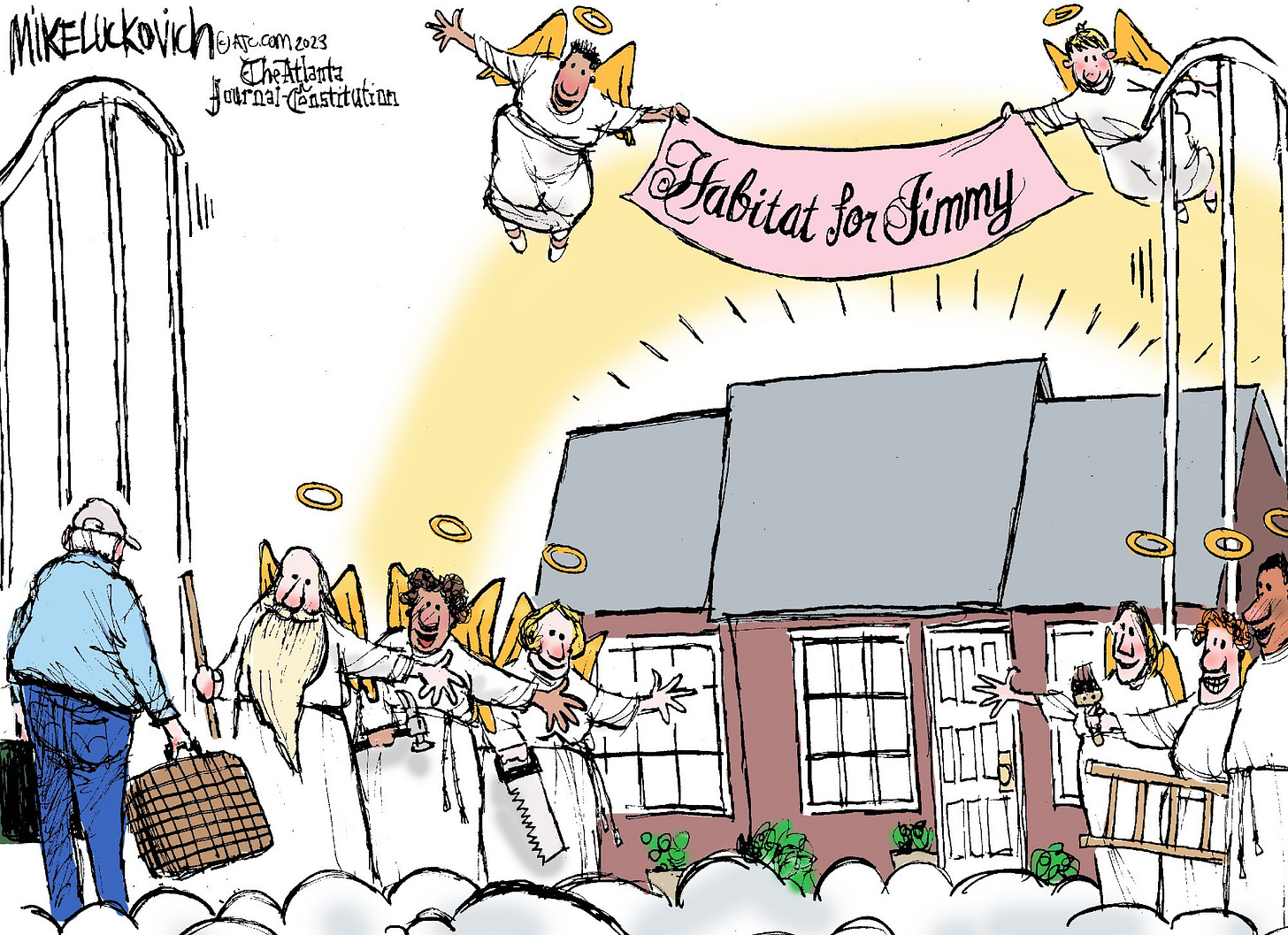

The second type of heavenly obituary cartoon focuses on some defining aspect of the person’s earthly occupation and simply projects it into the life to come. In the Tina Turner cartoon, Luckovich imagined Tina arriving in heaven to frontline the heavenly choir. In the cartoon below, he likewise imagines Jimmy arriving in heaven and picking up his Habitat for Humanity work where he left off on earth:

With Turner, this approach was effective in a reverse-icon way. Does it work with Carter? I don’t see how. This cartoon doesn’t appear to offer any perspective on anything, either as reverse icon or as true one. Carter’s work with Habitat for Humanity has definite religious and Christian implications, and it’s possible to find a transcendent angle on it in a cartoon like this, as we will see! But this approach isn’t it. The lack of real perspective is reflected in the emptiness of St. Peter’s remark: The cartoon acknowledges that Carter, a noted Habitat for Humanity activist, has “arrived,” but it has nothing more to say about him, really.

A heavenly choir is an established part of the iconography of heaven in popular culture. A singer like Turner joining the heavenly choir is a readily intelligible idea; that she would frontline the choir is the commentary (Turner is the GOAT). Building houses in heaven isn’t part of the iconography in the same way.

True, Jesus tells his disciples in John’s Gospel that he goes to “prepare a place” for them among the “many rooms” in his Father’s house. But what would it mean for someone like Carter to arrive in heaven and promptly go to work building houses? Is there a housing shortage in heaven? We might imagine Jesus allowing us in some way to collaborate with him in the life to come, but the idea of collaboration isn’t present here. Carter is just doing his own thing.

As aimless as Luckovich’s take on Carter in heaven is, the version below, a very similar execution from Darkow, arguably muddles the concept even more:

Even more than in Luckovich’s cartoon, Darkow’s Jimmy just seems bent on building houses—whether or not there’s any call for it! Is it a compulsion? Is the idea that Carter is so selfless that even heaven doesn’t know what to do with him? Does he even realize he’s in heaven?

Read as a reverse icon, we might say the point of the cartoon is that during his lifetime Carter kept on selflessly working to make the world a better place long after he had “done enough” or “earned his wings” or whatever. This would make Darkow’s cartoon a more exact counterpart to Luckovich’s Tina Turner cartoon: In his own way, Carter is the GOAT, more than good enough for heaven.

Yet where in the Turner cartoon St. Peter’s commentary overtly gives Turner her props, here St. Peter seems at best tolerant, if not bemused. The Turner cartoon suggests that Turner in heaven is fully appreciated and celebrated (perhaps even getting her due in a way that she didn’t always on earth?). This idea is absent in Darkow’s Jimmy cartoon.

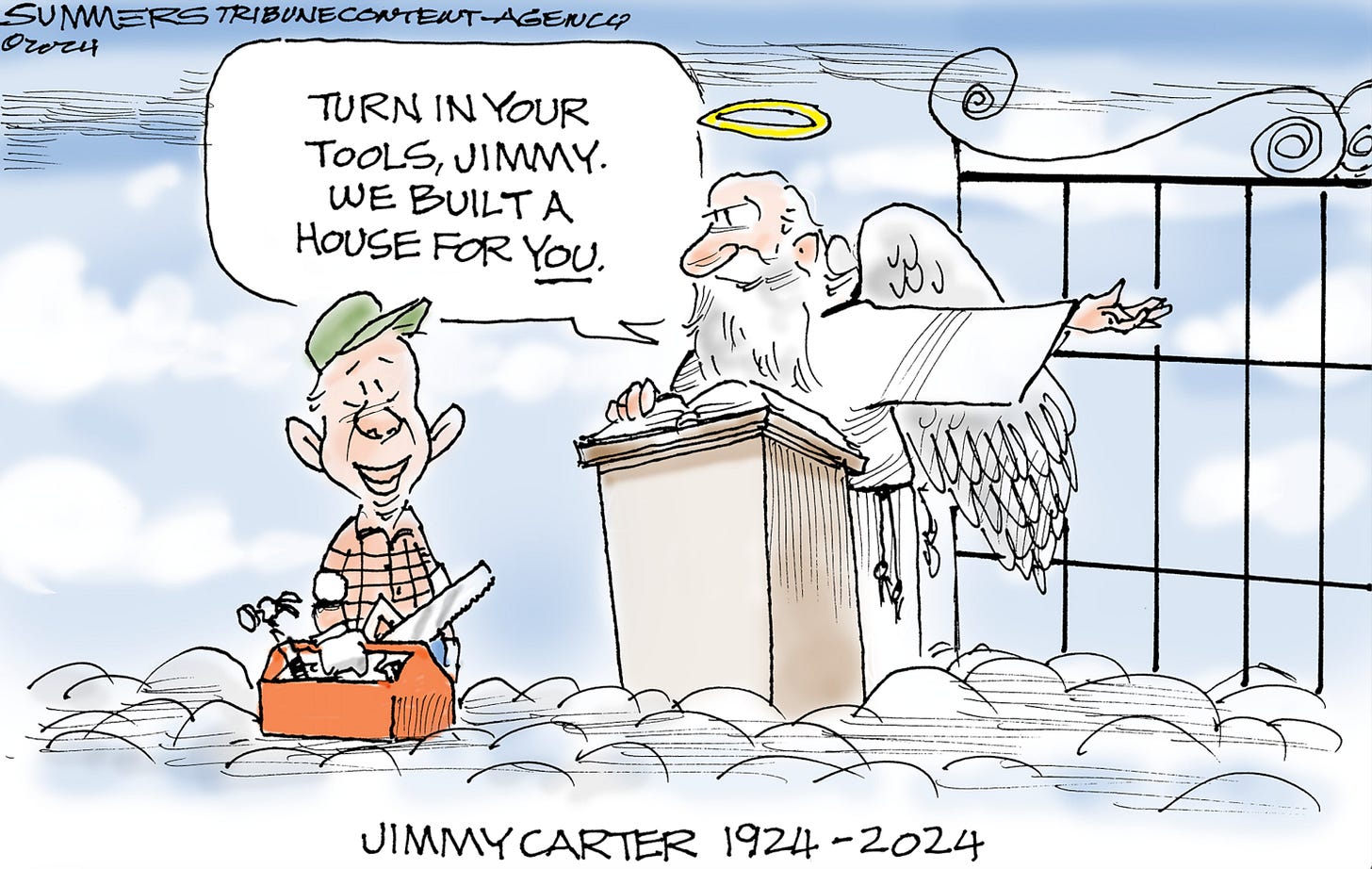

Finally, there’s this version from Scott Stantis (Chicago Tribune):

This version is something of an improvement in that a need is expressed and Jimmy’s ability to contribute is clearly valued; he isn’t just compulsively building houses because that’s what he does!19 For Christians, the mention of the Father’s “house of many rooms” implicitly suggests the collaboration with Jesus in “preparing a place” mentioned above. The wording of St. Peter’s comments, though, may be felt to raise questions about the scope of the cartoon: Does the need for Jimmy’s help point to some other theme? Is heaven in trouble for some reason? Is there, for example, an implicit critique of the Church (an absolutely valid theme, but perhaps a distracting thought here)? My feeling is that St. Peter’s smiling face suggests otherwise: The invitation for Jimmy to contribute is a wholly happy thought. How, then, does Jimmy feel about it? It might be nice to see him smiling too.20

Overall, it seems to me that where this second “heavenly occupation” class of obituary cartoons offered an effective way to commemorating Turner, for Carter the first “heavenly reunion” approach is more effective. As for true icon potential, a successful cartoon of the “heavenly reunion” sort seems to me more promising than one of the “heavenly occupation” sort. But there is one more approach to consider!

Approach #3: Eternal reward

The class of heavenly obituary cartoon that suggests eternal reward is probably the trickiest to pull off, but if successful may be the most moving and perhaps the most truly iconic. The catch is that you need a candidate whose ostensible worthiness and moral virtue are both widely recognized and readily invoked in iconographic terms.21 It helps, too, if the candidate’s virtue and the opportunity for reward lend themselves to a kind of reverse Dantean symmetry.22

In Carter, happily, we have an ideal case for such an approach—as the best of Luckovich’s Carter cartoon triptych illustrates:

The same Jesus who talked in John’s Gospel about “preparing a place” for us in the many rooms of his Father’s house also famously talked in Matthew about being hungry and thirsty and naked, and having his needs seen to (or not) by how we care (or not) for the least of these. Jesus’ words in this passage easily bear the expansion “I was unhoused, and you built a home for me.”

The idea of Carter’s work with Habitat for Humanity being rewarded with a “Habitat for Jimmy” is inspired and fully satisfying in a way that none of the previous cartoons are—not just as an obituary cartoon commenting on Carter’s life (a reverse icon) but as the real thing. This cartoon speaks to me more powerfully about invisible, heavenly realities than any of the foregoing.

That’s not all. The modesty of the heavenly bungalow is well-chosen. Make it an elaborate mansion, and you invite comparisons to every billionaire’s personal Xanadu … not to mention cost-benefit analysis … and suddenly it’s a cartoon about something completely different. The point of heavenly reward is happiness and appreciation, which doesn’t require a mansion. To this end, the welcoming angels23 who have worked for Jimmy as he has worked for others are essential to the cartoon’s success. Jimmy’s homecoming in this cartoon is a celebration. That’s what matters.

The most readily presentable alternative to the bungalow would be not to show the heavenly home at all—per this effort by Bill Bramhall (New York Daily News):

The catch here is that it may be ambiguous whether this is approach #2 or #3: Is Jimmy being welcomed to his reward or showing up for work? The version below by Dana Summers (Tribune Content Agency) clears up that issue:

This one is good, but of all the foregoing in all three approaches, Luckovich’s “Habitat For Jimmy” cartoon is far and away my favorite. The celebratory mood is everything: the beaming angels proudly waving Jimmy to the house they’ve built for him, tools still in their hands, and the “Habitat for Jimmy” banner honoring the personal nature of Jimmy’s reward.

Could the “Habitat For Jimmy” cartoon be even better? Maybe. If this is a proper homecoming, why not combine the best of approaches #3 and #1, and have Rosalynn there to welcome him as well? I wish, too, that Jimmy didn’t look quite so stiff and aged in this rendition.24 He’s arriving in heaven, not a retirement home! But these are asterisks to an outstanding cartoon.

One more!

As good as that last Luckovich is, there is one heavenly-reward Carter cartoon I appreciate even more—the most transcendent heavenly obituary cartoon, in fact, that I can remember ever seeing. From Michael Ramirez (Las Vegas Review Journal):

Oh. Oh my.

Ramirez jettisons nearly all25 of the usual iconography of such cartoons: No pearly gates or outer wall; no St. Peter at his lectern; no haloed, bewinged angels or saints; no new-arrival baggage. Instead, reflecting Carter’s deep Christian faith, Ramirez dares to depict Jimmy welcomed by Jesus himself.26 Carter’s work with Habitat for Humanity is invoked both by his toolbelt and by Jesus’ words “from one carpenter to another”: words that suggest both intimate personal understanding and approval, the “Well done, good and faithful” and “Come, you that are blessed by my Father” of Jesus’ parables of judgment. You can almost hear the Lord adding, “As you did for me, for the least of these, I’ve prepared a place for you.”27

On the editorial level, the message is, as always, this-worldly and reverse-iconic: As a believing Christian, Ramirez says, Carter walked the walk; he was a genuinely good man who had reason in the end to look back at his life with satisfaction and pride. Going a step further, we may choose to see, as a secondary message, the suggestion that in many ways Carter lived the kind of life that we might expect or may imagine would enjoy the approval of the kind of divinity that many Christians believe is revealed in Jesus.28

For me, though, this cartoon transcends the reverse iconic editorial, and speaks powerfully of the reality of eternal reward. Beyond the Savior’s embrace and the simple, powerful words “Welcome home,” the white light at the center of the image serves both as a halo for Jesus and as the unseen, unrepresentable destination to which Jimmy is being led. This goes beyond Luckovich’s heavenly bungalow—a lovely image that nevertheless flaunts its earthly, human, modern, and Western specificity in every muntin and pane of glass in the windows. Light, by contrast, is the most immediate and elemental of symbols. Light speaks of life and warmth and comfort, of truth and knowledge and wisdom, of hope and happiness and celebration. Of the divine. And the light here is identified both with Jesus and with “home.”

Like the Luckovich “Habitat for Jimmy” and some (not all) of the others, Jimmy is old in this cartoon. I like to think, looking at the “Habitat for Jimmy” cartoon and some of the others, that as Jimmy passes through the pearly gates, the years will start to fall away. This Ramirez cartoon, though, is different from the others in that the light is (as I interpret it) still in the distance. Jimmy is “home,” but there is clearly more to come (heaven is not just Jimmy and Jesus, so wherever the others are, Rosalynn included, is where they are going). He has a journey ahead of him—a journey with Christ as his companion and guide, but a journey nonetheless. How will this journey change him? Will he be young in the end? (For Catholics, this line of thought connects naturally to the doctrine of purgatory.)29

That nimbus of light, on what we might in earthly terms call the horizon, looks to be about the apparent size of the sun—but I can’t help imagining it (this is well past cartoon criticism here, but my iconic interpretation is my own) being revealed as a blazing fire greater than all the suns in the universe. The fire of divine love.

Very few editorial cartoons offer me a path to such thoughts. This truly transcendent cartoon does.30

Read more comics writing >

Technically, such cartoons tend to portray the “pearly gates” of heaven in what looks like wrought iron, often white-colored. The book of Revelation describes the heavenly Jerusalem having twelve gates, each gate made of a single pearl (Rev. 21:21). Like many images in Revelation, this one resists easy visualization or realization in art. These complications aside, in this article I will continue to use the “pearly gates” trope.

One root of the tendency to suppose that (almost) everyone goes to heaven is the strain of popular religion that has been called “moralistic therapeutic deism.” This term describes comforting belief in a remote, nonsectarian deity who is there for us when we want or need him, wants us to be good and kind and happy on our own terms, and is understood to reward good people with eternal life without much reference to ideas like sin and grace and redemption. There are also very different strains of thought in Catholic soteriology that lay great emphasis on the universality of Christ’s redemption, as well as on God’s universal salvific will, as the basis for daring to hope that those who are saved may include the vast majority of humanity (Pope Benedict XVI; see Spe Salvi), or even all of humanity (most famously Hans Urs von Balthasar; see Pope Francis’s 2024 remark “I like to think hell is empty; I hope it is”).

Sometimes the universalist tendency in obituary cartoons may get to be too much even for the cartoonists. When the full extent of Penn State football coach Joe Paterno’s knowledge of assistant coach Jerry Sandusky’s child rape was publicly revealed, it led to a reappraisal of Paterno’s legacy. As a result, Philadelphia Inquirer cartoonist Rob Tornoe (who is not religious) issued a cartoon mea culpa for his initially sentimental depiction of Paterno receiving a warm “Welcome home” from Alabama coach Paul “Bear” Bryant, instead depicting Paterno “in a place that knows how to deal with people who allow children to be raped”:

Granted, Turner often called herself a “Buddhist-Baptist,” but that’s the kind of label that comes far more easily to Buddhists than to Baptists! (As G.K. Chesterton once wisely cracked, “Christianity and Buddhism are very much alike, especially Buddhism.”)

In a few more words: “Tina is a one-of-a-kind legend who left a unique and lasting mark on popular music and culture.”

Some of the mysticism around the language and concepts of Eastern iconography lapses at times into pious distortion. It used to be common to insist that icons are “written” and not painted, with pious explanations about icons as visual scripture rather than expressive art in the Western sense. But this is a misconception based on the different ranges of verbs in Greek and Russian compared to roughly but not exactly equivalent English counterparts. The same verbs apply (or not) to making icons as making any kind of painting.

De rigueur recommendation of Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics.

As a counterpoint to the honored-dead rule of thumb, see note 2 above!

Here at All Things SDG, of course, we value both theological and cartoon literacy!

On social media I fielded objections to heavenly obituary cartoons from devout Catholics who felt such cartoons discourage prayers for the souls of the departed. One person wrote, regarding my favorite of the cartoons considered in this piece:

A virtuous and well-formed Catholic will not be tempted by the cartoon not to pray for President Carter’s soul…. But ordinary people without adequate theological formation will take the cartoon as implying that President Carter is in heaven.

My feeling is that no one who is at all likely to pray for Carter’s soul in the first place would likely be put off from doing so by such cartoons—and anyone who is at all likely to form a belief about someone being in heaven based on an editorial cartoon probably suffers at least as much from cartoon illiteracy as theological illiteracy! In both cases, I am here to help.

This threefold division is not intended to be an exhaustive taxonomy of heavenly obituary cartoons! They are just the three types of such cartoons that Luckovich happened to do for Jimmy Carter.

Not that sentimentality is a bad thing in itself! “It is as healthy to enjoy sentiment as to enjoy jam” (Chesterton, again!). But an editorial cartoon can be sentimental while also offering more than mere sentimentality, as we will see.

To be sure, not a trivial fact about any human afforded the opportunity to achieve such a thing! From an editorial perspective, though, not a particularly salient fact about a public life like Carter’s.

As C.S. Lewis, mourning the death of his wife Helen Joy Davidman, wrote in A Grief Observed:

Unless, of course, you can literally believe all that stuff about family reunions ‘on the further shore’, pictured in entirely earthly terms. But that is all unscriptural, all out of bad hymns and lithographs. There’s not a word of it in the Bible. And it rings false. We know it couldn’t be like that. Reality never repeats. The exact same thing is never taken away and given back. How well the Spiritualists bait their hook! ‘Things on this side are not so different after all.’ There are cigars in Heaven. For that is what we should all like. The happy past restored.

(“And that, just that,” Lewis adds miserably, “is what I cry out for, with mad, midnight endearments and entreaties spoken into the empty air.”)

In counterpoint to the Lewis quotation in note 12, the old 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia dares to argue:

We are created for love and friendship, for indissoluble union with our friends. At the grave of those we love our heart longs for a future reunion. This cry of nature is no delusion. A joyful and everlasting reunion awaits the just man beyond the grave.

See Ramsay’s similar (and, I would argue, more effective) tribute to Barbara Bush in note 9 above. That said, on a technical note, see how effectively, in the Carter cartoon, the dynamic, airborne poses that Ramsay gives his tiny, stylized figures conveys the speed of their motion toward each other. Luckovich’s more realistic approach to his larger figures is less successful: Despite mushroom-shaped speed lines/clouds indicating rapid movement, Jimmy’s static pose in particular nails his shoes to the cloud floor, and even Rosalynn isn’t moving as fast as her special effects suggest. The cartoon would work better without the speed effects.

In theology, positive assertions about what God is (or heaven, etc.) are cataphatic language, while negative assertions (about what God is not), or the evasion of assertion, are apophatic language. It is a truism in Catholic theology that all cataphatic (positive) language about God and heaven is analogical (based on analogy), while all univocal (literal, exact) language about God and heaven is apophatic (i.e., we can only speak exactly about God when we say what he is not; whenever we say what he is, we fall back on analogy). Read more about apophasis and cataphasis!

I like the juxtaposition here of Jimmy’s wrinkled, liver-spotted arm with the flawless skin of Rosalynn’s hand and wrist. Too many of these cartoons depict the new arrival in heaven at their age at death, white-haired, wrinkled, bent, etc. This is of course for the sake of recognizability, but I’d like the idea of agelessness in heaven to get more play in these cartoons. (As for recognizability, that’s why God created editorial cartoon labels!)

It’s also quite nice stylistically, e.g., St. Peter’s absurdly tall lectern rising from the clouds!

A slight change of wording might avoid any potential ambiguity: Instead of “Your Father’s house of many rooms could use your help,” how about “Your Father would like your help on his house of many rooms”?

I can imagine a religious article about Tina Turner’s life making a case for reasonably hoping to find her numbered among the saints. I wouldn’t want to try to suggest such a thing in a one-panel cartoon!

In his Inferno Dante created punishments that in some way fit the crime, a device he called contrapasso, meaning “suffering the opposite.” (Not to be confused, as I have for most of my life, with the art term contrapposto, meaning “counterpoise” and referring to a figure, such as a statue, standing nonsymmetrically with most of its weight on one foot, raising the hip on one side and the shoulder on the other!)

For example, the lustful in Dante’s second circle of hell are buffeted by howling winds, reflecting how they allowed themselves on earth to be blown to and fro by wayward appetites. A similar principle applies in Purgatorio, where the holy souls must endure burdens designed to purge them from their specific attachments to sin.

In Paradiso, by contrast, Dante has different levels of honor corresponding to different levels of virtue, but he does not propose specific rewards corresponding to types of virtue—like Carter’s heavenly bungalow in Luckovich’s “Habitat for Jimmy” cartoon. Still, I like to think that Dante would approve of this idea!

Whether they are literal Christian angels or humans who have “earned their wings” (as St. Peter has wings in most of these cartoons, and as Rosalynn has wings in the Ramsay and Englehart cartoons) is irrelevant for present purposes.

See note 10 above.

The one exception, of course, is the puffy clouds. Note, incidentally, the striking contrast between the ultra-simple, iconic cartoon clouds versus the richly illustrated folds on Jesus’ robes and the lovingly detailed work on Carter’s tool belt and textured pants. It’s almost like Ramirez is telling us what’s really important here!

For a Buddhist like Turner, directly depicting Jesus welcoming her might feel disrespectful in a way that “cartoon heaven” trappings like pearly gates don’t.

Commenting on the Ramirez cartoon, my friend Jon Trott suggested flipping the word balloon text from “Welcome home, from one carpenter to another” to “From one carpenter to another … welcome home.” I prefer the latter version too, but I understand why Ramirez might prefer the original text. Giving the final emphatic place to “from one carpenter to another” emphasizes the editorial point of Carter’s resemblance to Christ; the alternate wording would emphasize “Welcome home,” making the cartoon more overtly theological and eschatological, and thus less editorial.

It is perhaps not as quite needless to say as you might think that even the Ramirez cartoon is not a statement of faith that Carter is in fact in heaven—much less a suggestion that Catholics should not pray for Carter’s soul. (It’s an editorial cartoon, not a decree of canonization.) See note 9 for more context.

It is unfortuately necessary to say that while Carter was, of course, not Catholic, and while he took some positions at odds with Catholic teaching, the Catholic Church hopes and prays for the salvation of all. Carter was, again of course, a fallible and sinful man; he was also a serious Christian who made some serious effort to honor God’s word by his best lights. I write here about obituary cartoons; I also write as a Catholic who is hopeful and prayerful for Carter’s soul. What this is not is a post about all the good and bad in Carter‘s life. Comments devoted to criticizing Carter are discouraged. Comments involving uncharitable speculation about the state of Carter’s soul will be deleted with prejudice.

I’m not forgetting that I promised a ranking! There are ten Jimmy Carter obituary cartoons in this piece (not counting the Rosalynn Carter ones, which I can’t directly compare to the Jimmy ones). Among the three approaches, my favorites are the “heavenly reward” cartoons, followed by the “heavenly reunion” ones, with the “heavenly occupation” ones last. Among these, my preferences break down as follows:

Approach #2: Heavenly occupation (Jimmy keeps building)

Darkow (“Hey Jimmy! Take a break…”) I quite like Darkow’s cartoon of Rosalynn waiting for Jimmy at the pearly gates! This one doesn’t work for me at all, though.

Luckovich (“Did I mention President Carter arrived?”) Yes, he’s arrived. And?

Stantis (“Your Father’s house of many rooms could use your help…”) There’s potential here, but it doesn’t quite pay off for me.

Approach #1: Heavenly reunion (Jimmy and Rosalynn)

Luckovich (“Jimmy!”) Fine execution (poses a little static for the desired sense of movement; see note 16).

Ramsay (“Jimmy!” “Rosalynn!”) Slightly better execution (again, note 16). Note that Ramsay has one of the best and most beloved cartoons of this variety; see note 11.

Bennett (wordless). What can I say, I’m a sucker for walking off into the light! (See note 17.)

Approach #3: Heavenly reward (Jimmy comes home)

Bramhall (“Habitat for Eternity”) Good, but is Jimmy receiving his reward, or showing up for work?

Summers (“Turn in your tools, Jimmy…”) Clear and satisfying.

Luckovich (“Habitat for Jimmy”) Outstanding. Deeply moving and heartfelt. A true icon.

Ramirez (“Welcome home, from one carpenter to another”) Transcendent.

I think you are looking at method #2 (Carter doing habitat for humanity work in Heaven) to literally and theologically. I think you need to look at it as hyperbole that is not meant to truly reflect Heaven.

The idea is that Carter was the GOAT of service. It is akin to saying “He would even be helping Heaven build houses rather than take time off.”

Just as we don’t literally believe that Tina would be headlining some choir in Heaven, we are not meant to believe, literally, that President Cater would be building houses in Heaven (or that Heaven would need houses built)

A marvelous analysis of a genre you have thoughtfully helped me, may I say, dislike a bit less...?