Is it possible to know God? How can anyone claim such a thing? What would it even mean? To “know” the incomprehensible, unimaginable, absolutely Other? To have a relationship with an invisible, silent partner: to converse with One whose very existence must be taken on faith? Where do you even start with such a thing? Granted the existence of infinite, omnipotent, omniscient Being behind all that is, how should our ideas about such divine mystery amount to anything but projection and imagination, hopes and fears?

Even in human relationships, it’s not uncommon for one person’s ideas about another to reflect their own biases, needs, or fears—sometimes to such an extent that an apparent relationship is more imaginary than real. In such cases, of course, the false ideas may at any time be challenged or exposed by the other person’s actual words or behavior. When this happens, in a moment of insight, one may find oneself saying things like “I thought I knew that person, but I never really did.” How much more must this be the case with God, where no overt word or behavior threatens to derail our preconceived notions? How is prayer anything but talking to our own imaginations?

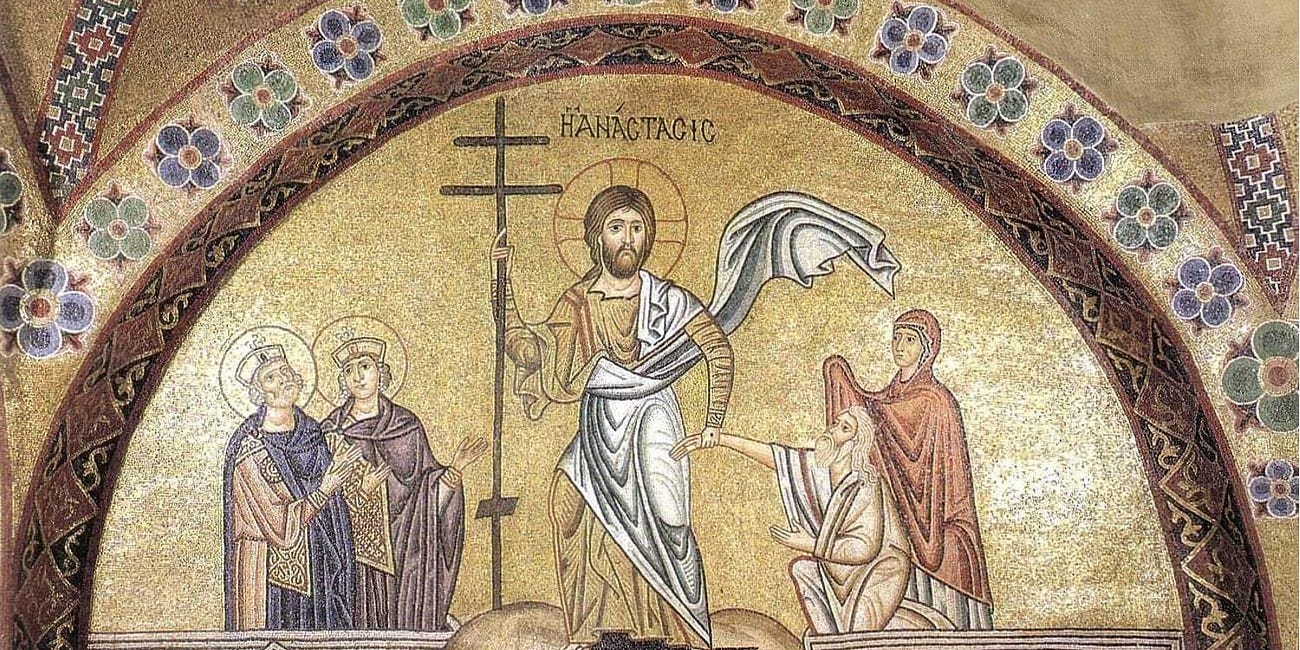

Christianity proposes that God has acted in the world to make himself known in many ways, but above all through Jesus, who shows us, in a unique and definitive way, the face of God:

Long ago God spoke to our ancestors in many and various ways by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son … He is the reflection of God’s glory and the exact imprint of God’s very being, and he sustains all things by his powerful word. (Hebrews 1:1–3)

This is, for believers, a singularly world-changing idea. If we can accept this, it is possible to hope to find meaningful insight into the character of God in what the Gospels tell us about Jesus’ words (from the Sermon on the Mount and the excoriations of religious hypocrisy to the parables of the Prodigal Son and the Good Samaritan etc.) and actions (forgiving sins, healing the sick, exorcising demons, and ultimately laying down his life in an act of redeeming love).

Of course there is the unavoidable reality that Jesus himself is understood in vastly different and contradictory ways by different types of people. Cultural forces and cognitive biases inevitably color what we see in the Gospels; notoriously, even biblical historians seeking to reconstruct the historical Jesus have often come up with pictures strikingly resembling themselves.1 Still, the Gospels are at least a place to start, and we can hope to come to some kind of insight into what sort of God might have expressed himself to the world through Jesus.

Yet even then, knowledge is not the same as relationship, and Jesus in his humanity is no more available to us for two-way conversation than the divine nature. What does it mean to know Jesus—to have a relationship with a man who walked the earth 2,000 years ago, even one who has transcended death?

Universal light

These are not rhetorical questions. Lifelong believers struggle with these questions. I have struggled with them, and the way I think about them now is not necessarily the way I thought about them, say, when I first became Catholic.

Today I find it helpful to begin here: If the divine nature is anything like what the Christian tradition tells me, or even what some Greek philosophers like the Neoplatonists affirmed, God is not something completely unknown to me, or to any human being. The prologue of the Gospel of John, which tells us that in Jesus the divine “Word became flesh,” also calls him universal light:

In him was life, and this life was the light of the human race. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it… The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world. (John 1:4–5, 9)

Such divine light is not simply unknowable mystery—with or without the revelation of Jesus. The light that Christians believe shines with unique clarity and brilliance in Jesus is in some way not entirely absent wherever human beings are found. This is not to discount the profound darkness that has often prevailed in both non-Christian and Christian societies. Even in darkness, though, John says that light shines unconquered.

I’m not suggesting that everyone knows God, or that God is equally knowable everywhere or by everyone! But I think divine light in some degree is discoverable anywhere, by anyone who seeks it. Indeed, the very act of seeking I believe is already a sign that divine light is at work. Jesus, encouraging his hearers to trust God, tells them that, even though they may be evil, they still know enough to give good things to their children (Matthew 7:7–11). This is a low bar (one which, nevertheless, some parents fail to clear)—yet even this, for Jesus, is a narrow window that shows us something of God.

The Greek term for “word” in John’s prologue, the divine Word made flesh in Jesus—logos (λόγος)—has other meanings and connotations, including “message,” “idea,” “law,” “reason,” and “rationality.” It is the root of “logic” and the “-logy” in the sciences (biology, cosmology, theology, etc.). Some Greek philosophers like the Stoics used logos to mean the principle of reason pervading the universe, and Hellenistic Jews connected it to the divine Wisdom (chokmah, חָכְמָה) through which God created the world. If we are created in God’s image, human rationality in some dim way reflects divine reason, and in discerning the rational structure of reality we “think God’s thoughts after him,” as a phrase associated with the pioneering astronomer Johannes Kepler puts it.2

The One who knows me

Following Plato and Aristotle, Christian philosophers including Augustine and Aquinas have seen in qualities like truth and goodness3 transcendental reflections or rays of God.4 “God is truth,” St. Edith Stein wrote in a 1938 letter; “all who seek truth seek God, whether this is clear to them or not.”

God is more unknown than known. Yet he is not entirely unknown, not wholly we know not what. Whatever we know by conscience of the good and of truth by the intellect, Christian philosophy sees as transcendental signposts of the integral perfection of God. All truth and goodness are God’s, and of God. Everything in our lives that is sound and wholesome and lovely speaks to us of God. The quest to know God is like the drive of green plants to grow toward the sunlight in which is their health and wholeness; our deepest needs and best insights provide meaningful guidance.

It is doubtless true that we all labor under mistaken assumptions and misunderstandings about God’s character. And, compared to our relationships with human beings, these misunderstandings are less subject to unexpected cross-examination by unexpected words or actions (though actually this can happen with God as well). On the other hand, human beings are idiosyncratic, variable, and contradictory, while God cannot be other than perfect and absolute Being. Trying to know another human being, then, can be something like a game of hide-and-seek; they might be anywhere, in any direction, behind any bit of cover. Trying to know God might be (to return to the metaphor of the last paragraph) more like trying to locate the sun on a cloudy day. Its exact location may be obscure, but you have a meaningful idea of where it is and where it isn’t.

The sun is a massive and vital presence in our daily lives. It’s also some 93 million miles away. While God is incomprehensibly Other, as the Creator and the ground of Being, he’s also closer to us than any creature: intimately, inseparably at the root of all existence, including ours. Simply by existing, we are in relation to God; by mere awareness of this fact, that relation becomes personal, because God is always aware of us.

This is where prayer begins for me: not with God as the object of my attention or knowledge, but with myself as the object of his. Knowing God, for me, begins with the conviction that I am known to God, so I know God first of all as the One who knows me—knows me, in fact, far better than I know myself.

Not only do I labor under misapprehensions of who and what God is, even my ideas about myself are hardly the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. God, then, is the One before whom I stand as I really am; in awareness of God’s presence, I become in some degree conscious of the reality of what I am beyond my own knowing. Whatever poses I may wish to strike, whatever distorted ideas of myself I may cling to, God sees through it all. In every other relationship in my life, some kind of social self intervenes between me and other people. Before God, I am fully, truly myself.

Love and “I” contact

Neoplatonism teaches me to understand God via the transcendental qualities of truth and goodness—but Christian faith teaches me that the greatest and most profound truth of all is that God is love. The sun is indifferent to the green plants growing toward it, but God is not indifferent to us. God is not just the One who knows me, but the One who loves me, who draws me to himself.

Prayer is an act of faith, not just in the sense of belief, but also in the sense of trust. Faith calls me to trust that whenever I seek to lift my heart and mind to God, not only is God’s gaze already turned toward me, my very impulse to turn to him, my impulse to pray (however halfhearted or doubtful, etc.), is already his work in me. There is no need for me to try, as it were, to get his attention, or to work myself up into the right frame of mind, or formulate the proper idea of who God is before I can address myself to him. I am invited to trust that he is there for me, bigger than every obstacle of my finitude and fallibility. Prayer is his gift to me; in actually praying I only accept his gift.

What emerges from spending time this way, even if there is no communication as such from God to me, is akin to making eye contact. What happens in eye contact? One moment you’re alone in your own thoughts, a self-contained “I”; next moment you become aware of another person’s gaze, and in that moment you’re reflexively aware of what you call “me” and “myself” and “I” as the other person’s “thou,” while they, an “I” in their own right, are now your “thou”—and a new, shared personal identity called “we” appears. Something like this happens in prayer, but instead of eye contact, it’s “I” contact. I’m not talking about a mystical experience per se, although this can follow, but about awareness based in faith. The mere fact that I am known to God, and that I know he is there knowing and loving me, makes me his “thou,” and he himself, “I Am Who I Am,” is my “thou,” and a real and meaningful “we” emerges.

These reflections are only a beginning, but when it comes to prayer, beginning is everything. The reality plays out differently in differenst contexts: in liturgical worship, in reading the scriptures, in doing good in the world, and so forth. Prayer changes over time in many ways and for many reasons, and how we pray early in life (earthly life or spiritual life) is different from how we pray later on. I’ve shared these reflections because I find them helpful, and you may too. But action is more important than theory, and the first and most essential part of action is to start.

See also

Reason and faith: Thoughts about trust and knowledge of reality

Question from a young Catholic correspondent:

A religious epistemic hierarchy: What I believe in 18 theses, ranked

This is a follow-up of sorts to last week’s reflections on reason and faith. For some time I’ve been mulling over the notion of trying to organize my religious beliefs in a some kind of epistemic hierarchy or ranking. That is, as a Catholic Christian, what is most foundational to me …

A famous quip about the scholarly quest for the historical Jesus amounting to various scholars looking into the well of history and seeing at the bottom the reflections of their own faces was originally made by Adolf von Harnack in regard to George Tyrell, but later generalized by William Lane Craig.

Kepler may or may not have used this phrase, but it certainly expresses his thought. The quotation commonly found online that links this phrase to an authentic Kepler quotation about astronomers as “priests of the highest God in regard to the book of nature” is a conflation.

In modern times the transcendentals are often enumerated as goodness, truth, and beauty. This triad, with beauty, is a modern formulation; goodness, truth, and unity or oneness is a more traditional formulation, although there is some precedent in premodern times for numbering beauty among transcendental qualities. More on this in an upcoming piece.

One of my favorite formulations of this principle comes from Pope Pius XII in a text of some importance to me as a Catholic film writer, a pair of addresses to filmmakers on the “ideal film.” In this text Pius calls goodness, truth, and beauty “refractions, as it were, across the prism of consciousness, of the boundless realm of being, which extends beyond man, in whom they actuate an ever more extensive participation in Being itself.” Toward the end he says the same thing much more simply: Any “reflection of the true, the good, the beautiful” is simply “a ray of God.”

Excellent article, Deacon. I haven't read many books about praying, but the best that I have read is Prayer for Beginners by Peter Kreeft. It's short and accessible, as it should be, but also insightful. I heartily recommend it.

Jack loved your piece about knowing God. He told me to be sure I didn’t miss it!