Sex and death: Entomological fun facts!

[NOT about ETYMOLOGY…and not really a Cartoon Critic post]

This is not a Cartoon Critic post … exactly! Just a post that takes cartoon art as a springboard for some scientific observations about the facts of life—and death, and sex—in the arthropod world. (Technically, some of my observations go beyond the insect class, so “entomological” may not be strictly accurate, but I couldn’t resist the wordplay on the title of a recent post, about etymological fun facts!1)

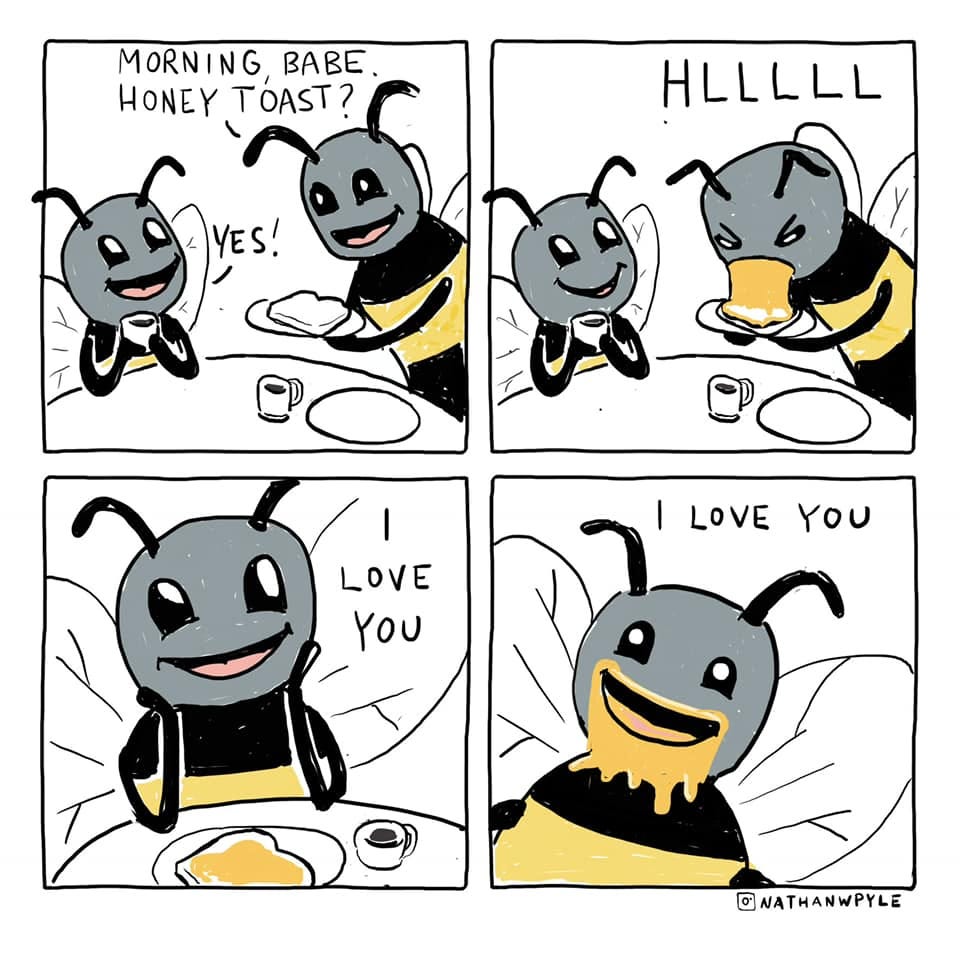

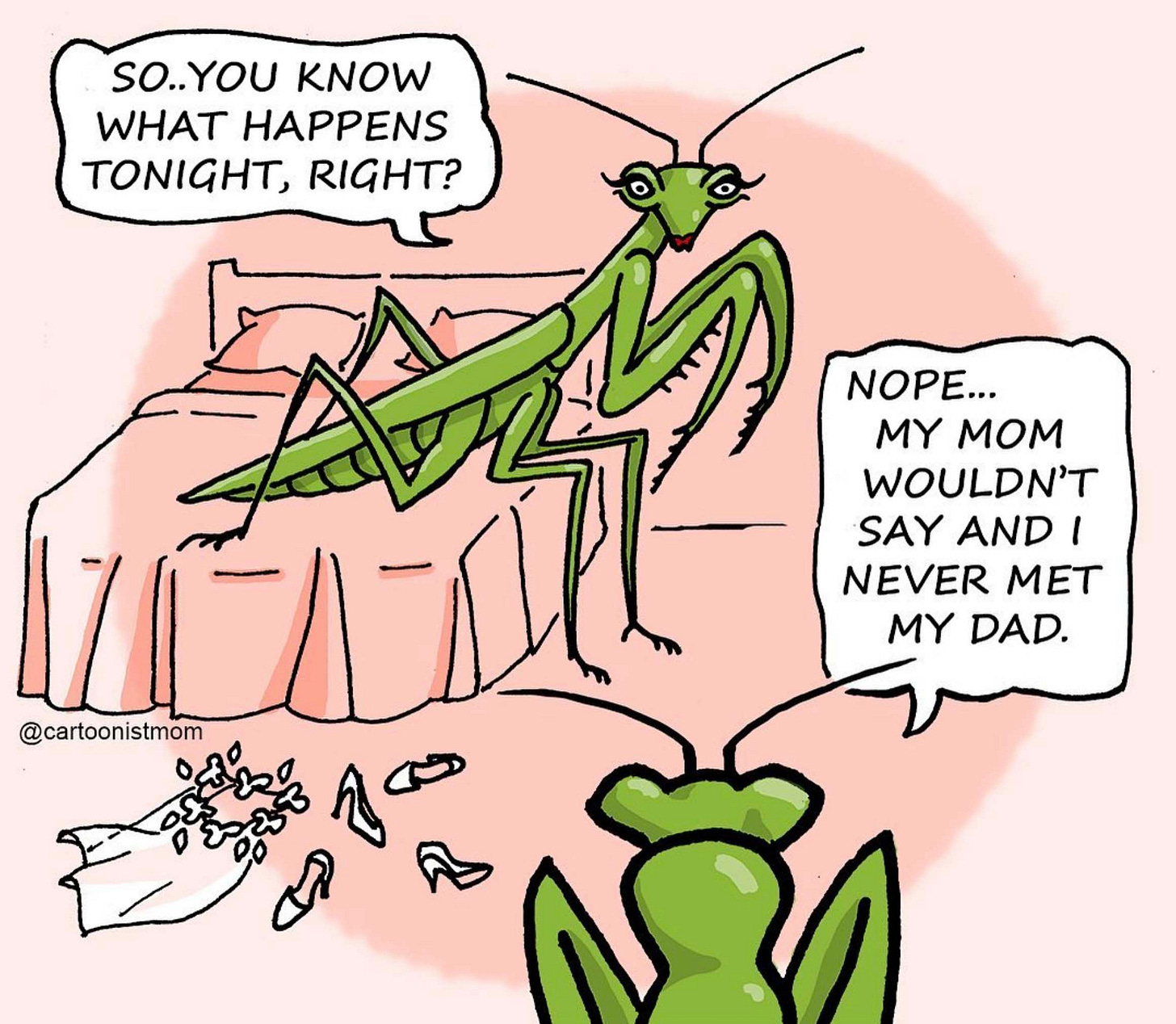

The praying mantis cartoon (on the left above) is from a cartoonist who posts anonymously on Instagram as @cartoonistmom. The one with the honeybees (on the right above) is from Strange Planet cartoonist Nathan Pyle. Since I have more to say about honeybees than mantises, let’s look at that one first!

The, um, gag here, of course, is that worker bees produce honey by a process of regurgitation, which, anthropomorphically reimagined, seems super gross. True enough! Caveats and notes:2

I wish this strip offered clear visual cues as to the sexes of the bees! (Again, not a Cartoon Critic post, but I can’t help myself.) The overtones of domestic affection (“Babe” and “I love you”) suggest to me a romantic/sexual partnership—manifest nonsense, but what kind of nonsense it may be is less clear!3

Most obviously, the cartoon makes entomological sense only if the serving bee is a female worker. As is well known, worker bees who harvest nectar and manufacture honey are all (like the queen) female, while male drones subsist entirely on honey (and gland secretions) provided to them by workers. It would be easy to assume, therefore, that the bee being served is a drone.4 Yet it is also true, if perhaps less well known, that female workers also feed and care for one another!5 For what it’s worth, drones have larger eyes than workers (the better to spot a young mating queen at a distance in the midst of a cloud of drones) and stouter bodies (built for speed, the better to pursue the queen and seek to mate with her before a rival male). Pyle’s renditions aren’t definite enough to support firm conclusions (and he may not have researched these fine points anyway).

It’s well known that worker bees don’t mate; the only sexually mature female in a colony is the queen. Less well known, perhaps, is that even worker bees may be capable of reproduction—but not sexual reproduction! Rather, under rare conditions, workers can lay unfertilized eggs, which hatch into (surprise!) drones.6 This is surprising because in most species in which females are capable of parthenogenesis (asexual reproduction), offspring without a father are always female (essentially clones of their mother). What makes bees different is that, whereas in most sexually reproducing species both males and females are diploid (having two sets of chromosomes), in bees only females are diploid, while males are haploid (having just one set of chromosomes, like sperm or eggs).7 Thus, a queen (who reproduces both sexually and asexually) can choose to have male or female offspring at will by either fertilizing individual eggs or not, but workers who procreate have only male offspring.8

It’s well known that a drone’s main purpose is to be sexually available for mating with a queen.9 Less well known, perhaps, is that drones do not mate with the queen of their own hive! Rather, each colony maintains a population of drones to be available for mating with young queens from other colonies. This promotes genetic diversity and prevents colonies from becoming inbred.

The way it works is this: Each day, weather permitting, drones leave their hives to congregrate with other drones in areas called, um, drone congregation areas. These areas—which have clear boundaries that only bees understand—are located between 15 and 130 feet in the air. Drones gather in these areas on the lookout for visiting young mating queens.

A newly hatched virgin queen in search of drone congregation areas generally travels further from her own colony than local drones, ensuring that she will mate with drones who are not from her own colony.10 When she enters the drone congregation area, she will mate in midair with about 10 to 20 drones before calling it a day. Over the next several days, weather permitting, the young queen will return for more sex, ideally collecting millions of sperm from dozens of partners in an organ called a spermatheca. After this brief period in her early life, the queen’s mating days are over. Over the next several years, she will lay hundreds of thousands of eggs, using the stored sperm to fertilize eggs that will develop into new workers (or, for those select few females who are raised on royal jelly, new queens), or, if she wants drones, leaving the eggs unfertilized.

A drone who succeeds in mating with a queen doesn’t live to enjoy his success for long; in fact, his success is quite literally explosively fatal! Within seconds, all his blood (bee blood is called hemolymph) rushes to his sex organ,11 leaving him paralyzed, and the explosive ejaculation—so forceful that it can make an audible popping sound—typically ruptures the phallus, leaving the tip inside the female as the male falls and dies. Drones that don’t successfully mate with a queen (which is the vast majority of them)12 are generally driven out of the hive in the autumn and die. (Assuming the seated bee in the cartoon is male, if he thinks life is all being fed honey and gland secretions by females, he’s in for a rude awakening.)

In short, anthropomorphized bee-havior could get a lot weirder than what we see in this strip! Speaking of rude awakenings, let’s return to the praying mantis strip and the young suitor who never knew his father. (One small touch in this strip I love: the four high-heeled shoes on the floor!)

The gag in this strip rests on the well-known phenomenon of sexual cannibalism, a behavior (or range of behaviors) particularly associated with black widow spiders and mantises, and also found among some snakes, mollusks, and gastropods, among others. As the name implies, sexual cannibalism involves one of the partners (usually the female, who in these species is generally larger and heavier than the male) eating the other before, during, or after copulation.

The phenomenon is real, if complex, not entirely understood by scientists, and somewhat misunderstood in popular thought. For example, despite the “widow” name, sexual cannibalism is rare among many species of black widow. Exceptions include redback spiders or Australian black widows—as male redbacks actively sacrifice themselves to females during sex!13 Rather than angling for a hasty coupling and a quick getaway, these committed males trade their lives to copulate longer and fertilize more eggs, in the process leaving their mates less likely to accept subsequent suitors.14 This contrasts with the more normal tendency for at-risk males to employ strategies to avoid being eaten; for example, male spiders of some species may distract the female with a meal, or restrain her by webbing her up. Such efforts are not always successful; adding insult to injury, cannibalism can be an extreme form of rejection during attempted courtship. In some cases males also may eat unwanted female partners, or even, in what seems to be maladaptive behavior, eat females after mating with them.

Among mantises, rates of sexual cannibalism vary with the species, from less than 15 percent to up to 50 percent for the Chinese mantis. Male mantises, like males of most species, are not eager to be dinner, and therefore tend to angle toward a quick copulation and a quick getaway. However, the female has the power in this relationship, and is known to eat males before, during, and after mating.

In most species, a female eating a male (or vice versa!) “before mating” implies that mating doesn’t occur—but not with mantises! Specifically, a male mantis whose head has been literally chewed off is still capable of functioning for hours, and can manage to mount the female and copulate with her. In fact, because the male’s self-preservation instincts stem from its cephalic ganglions (the nerve center in its head), while copulatory movements are controlled by abdominal ganglions, a decapitated male mantis’s copulatory movements may be stronger and longer-lasting than a male that hasn’t lost its head.

To sum up:

For male bees, the intensity of sex causes sudden death, and means that copulation is necessarily brief.

For male redback spiders, death is potentially the price of longer-lasting sex.

For mantises, death may lead to more intense, longer-lasting sex.

Le petit mal, le grand mal!

See also

Plant and animal sex, what Aquinas and Aristotle didn’t know—and how it still affects our language

Awhile back I wrote a kinda sciencey, kinda cartoony post about the sex lives of bees and praying mantises. Among other things, I noted that even worker bees, in rare conditions, are capable of reproduction. Actually, worker bees are regularly engaged in reproduction—just not bee reproduction!

Specifically, I have some fun facts about spiders, which are (as all Spider-Man fans know) arachnids, not insects, and thus belong to the field of arachnology rather than entomology (which is very unhappily not, of course, the study of Ents, but of insects). I nevertheless take comfort in knowing that, in practice, entomologists often study non-insect arthropods like spiders, whose worlds after all heavily overlap with insects!

A caveat on the caveats: As with many (not all) posts here at All Things SDG, I write as an interested student, not an expert, in many topics; I am not an entomologist, and as always I welcome input from anyone who knows more than I do! (You didn’t know I was interested in entomology, did you? I have layers, my dudes.)

An alert reader suggests that the relationship between the two bees could also be interpreted as a parent/child relationship. (“Babe” to my northern NJ ears is primarily a romantic term of endearment, but I’m sure there are plenty of parents who use this term for their children!) Of course the serving bee can’t be the literal mother (or, obviously, the father) of the seated bee! But she could be an older sister acting in a maternal role toward a younger sibling. This is clearly the best way to read the cartoon, and perhaps how it was meant all along by Mr. Pyle. If so, perhaps “Kiddo” instead of “Babe” would have been the clearer term of endearment. And so this is a Cartoon Critic post after all!

A young drone, perhaps, as older drones feed themselves from the hive’s food stores.

Workers are also entirely responsible for feeding the laying queen, whose capacity to lay up to 1,500 eggs a day—more than her body weight—keeps them busy!

Worker bees normally lay eggs only in the absence of a queen. Naturally, a colony cannot survive without a mated queen laying fertilized eggs that produce females, most of whom will be workers and a few of which will develop as virgin queens. Queens that fail to mate are also consigned to producing only drones. Such a colony will probably die, unless a virgin queen who has fled from another colony to avoid being killed by a rival happens along.

Would you be astounded to learn that this genetic and reproductive strategy (diploid females, haploid males) is called … haplodiploidy? This means that every sperm from every drone contains the drone’s complete genetic code; unlike females, drones do not produce gametes through a process of meiosis, or cell division in which their genetic code is divided in half.

This means that female bees have a father and a mother, but two grandmothers and only one grandfather! It also means that drones have no sons, only daughters and grandsons.

Drones may also be called upon to assist in thermoregulation of the hive, e.g., fanning their wings to help cool the hive.

Practical considerations contribute here: Being larger than queens (the better to pursue queens, etc.), drones can’t travel as far, and they can only hang around the drone congregation area so long before having to head back to the colony for refueling services provided by their sisters.

This is called an endophallus, as it is normally an internal organ until he is ready to mate, at which point, inflated by blood, it everts (or turns inside out) into the queen’s sting chamber (if it is fully opened; if not, he is thwarted). The sperm are then explosively transferred into the oviduct and ultimately into the spermatheca. (I think I’ve got that right; I hope someone will tell me if it isn’t!)

Colonies produce far more workers than drones (tens of thousands compared to hundreds), but even so very few drones succeed in mating with a queen (perhaps only one in a thousand!).

At least, male redbacks tend to sacrifice themselves when they mate with mature females. Male redbacks have also developed a tactic (almost equally queasy in anthropomorphic terms!) for mating safely with immature females. A young female’s reproductive organs are covered by a protective shell which is shed on reaching adulthood—but, by penetrating this shell with their fangs, males can deposit their sperm in the immature female’s spermatheca, with normal fertilization following when the female reaches maturity. Researchers have found no negative consequences for either sex for this seemingly “coercive” mating strategy.

One factor in this strategy is that a typical male redback spider, like a typical drone bee, is unlikely to have even one chance to mate with a female; thus, the lucky male who finds a female is reasonably highly invested in making the most of this singular opportunity, as opposed to going for a quick pairing and a quick getaway.

I could stop at "The, um, gag here ..." and this piece would still be the funniest thing I've read in weeks. Thank you!

A fascinating read! Thank you for straying into topics not involving film or theology from time to time. The layers are appreciated!

Also, I grew up in the country and kept bees for a number of years. You have clearly done your homework here. There is some specific terminology not mentioned above (e.g., worker bees who lay eggs are called -- guess what? *Laying Workers!* They develop ovaries due to the lack of pheromones from a missing or failing queen.), but I have nothing to critique and quite a bit to complement.

Happy New Year! Looking forward to future writings.