Plant and animal sex, what Aquinas and Aristotle didn’t know—and how it still affects our language

[yes, flowers DO produce eggs…plus a Marian coda!]

Awhile back I wrote a kinda sciencey, kinda cartoony post about the sex lives of bees and praying mantises. Among other things, I noted that even worker bees, in rare conditions, are capable of reproduction. Actually, worker bees are regularly engaged in reproduction—just not bee reproduction!

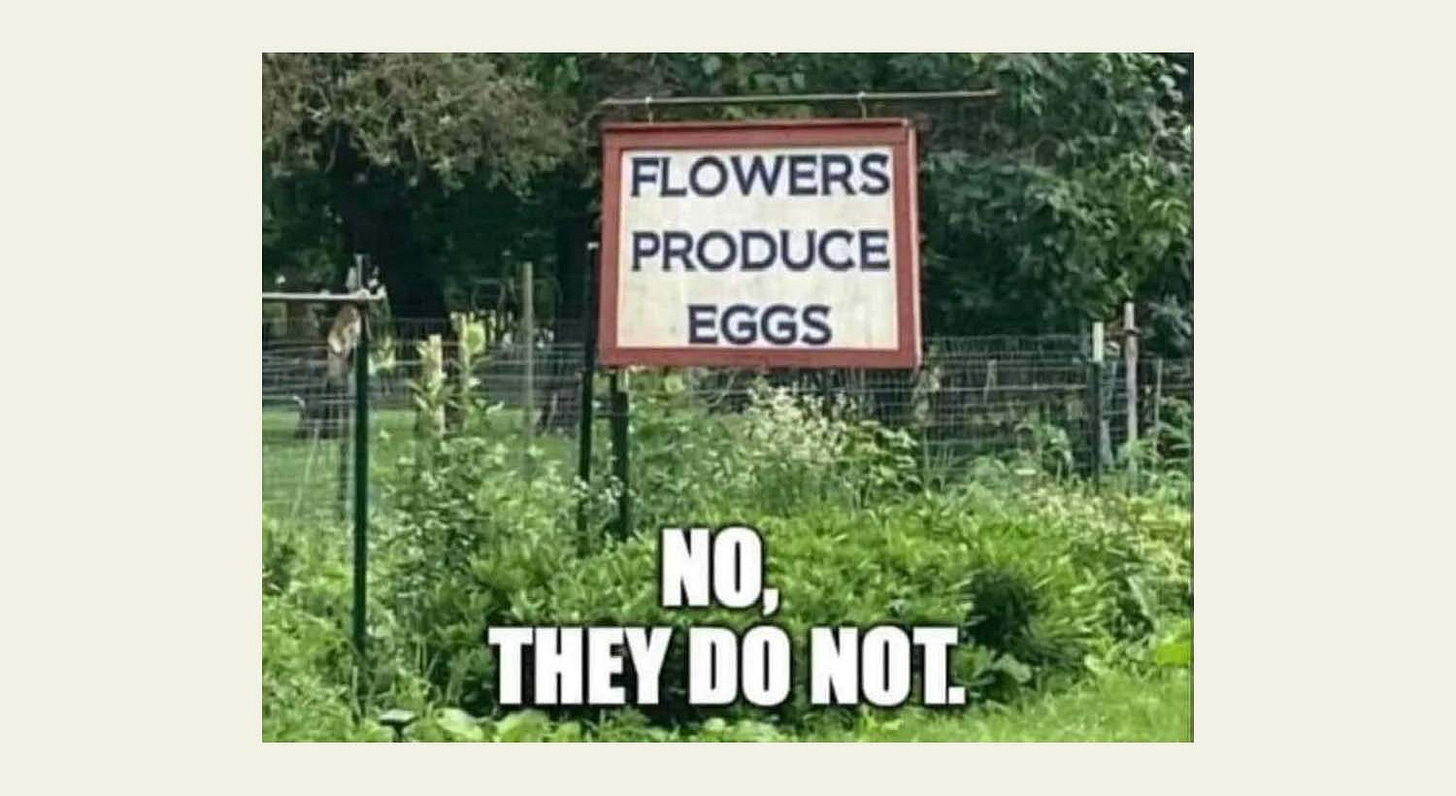

The meme above is, of course, a riff on the ambiguity of “produce,” which, depending on pronunciation, is either a noun referring to fruits and vegetables or a verb meaning “to bring forth.” And of course the type of eggs intended by the sign1 are produced, not by flowers, but by chickens, nyuk nyuk nyuk. The thing is, once you strike that Vulcanesque “logical” pose for the sake of a joke, you invite all players to the table—and, really, there are much more interesting points to be made about flowers and eggs than the one made by this meme!

Points, for example, that highlight the curious ambiguity of terms like “seed” and “fertile/fertilize,” which mean deceptively different things in relation to fundamentally similar plant and animal reproductive processes (as well as “fruit,” where there is really no analogy). This seems to be due to the fact that the language we use developed long before humans fully understood how sexual reproduction in both animals and plants works (in particular, before the female genetic role was understood)—and before we understood that reproduction in plants had a sexual component at all.

Flowers are vegetative organs of sexual reproduction.2 Some flowers contain female reproductive structures, others contain male structures, and still others (variously called hermaphrodite, bisexual, or perfect) contain both male and female structures.3 Flowers with male structures (stamens) produce pollen grains containing male gametes (sperm). What we call “seeds” are produced by flowers with female structures (pistils)—but only after fertilization. Pistils contain female organs called ovaries, just like in female animals. In animals, ovaries produce female gametes, called ova, or eggs; flower ovaries produce what are called ovules. An ovule contains an embryo sac which produces an ovum, or egg cell. So, yes, flowers produce eggs! (At least, some flowers do.)

Just like a animal ovum, the plant egg cell, when fertilized (often by a pollinator, such as a bee, gathering nectar for food), becomes an embryo—which then, however, develops into what we call a seed. All plants that produce and grow from seeds (whether or not flowers are involved) are called spermatophytes (sperma being the Greek word for “seed,” and obviously the root of the English word sperm).

Here’s the linguistically confusing part: In animals, “seed” and “sperm” are synonymous terms referring to male gametes, and the seed and the egg together make the embryo. In plants, by contrast, the seed is produced by the female ovary after fertilization—and the seed develops from the embryo! Another linguistic oddity: The term fertilization in biology refers to the fusing of male and female gametes, leading to the embryo, but in agriculture “fertilization” merely means improving soil quality. These vagaries of divergent language actually obscure fundamental similarities of the plant and animal reproductive processes—obscurities linked to limited and erroneous premodern ideas about both processes.

One thing that was understood in the ancient world was that plant seeds contain the entire plant in embryonic or potential form; all that is needed for the seed to grow into the adult plant is to be sown in fertile soil under suitable conditions. A common ancient error lay in applying this model by analogy to a mammalian male (such as a human) impregnating a female: The male “seed” or sperm was mistakenly thought (on the analogy of plant seeds) to contain the entire individual in potential form, and female fertility was thought to be analogous to that of “fertile” soil, her role limited to providing a suitably nurturing environment for the seed to mature.4

Eggs were known in premodern times, of course, in connection with the reproductive processes of birds and other oviparous5 species. The existence of vegetative eggs and mammalian eggs, and the equal hereditary contributions of mothers as well as fathers, though, was unknown until modern times.6 Of course there was no notion whatsoever of genes, chromosomes, and the process of meiosis creating male and female gametes representing half of each parent’s DNA.

So, for example, Aristotle was aware that individual honeybees tend to forage from the same type of flowers, but he didn’t understand that this behavior assisted in plant reproduction by spreading pollen from male stamens to female pistils.7 In animal reproduction, Aristotle held that a healthy embryo allowed to mature in ideal conditions and achieve its full potential would naturally be a male resembling his father; both girls and children (of either sex) resembling their mother (or more distant relations) he considered products a process of development in some way defective: “The female is, as it were, a mutilated male” in the appalling phrase of Aristotle infamously echoed by St. Thomas Aquinas.8

Movie-related aside: There is a deeply lame 2007 animated movie, Bee Movie, starring (and pitched and co-written by) Jerry Seinfeld, that botches both bee and plant sex so profoundly that one could only imagine it coming from people as patently urban as Seinfeld. In this movie, male bees are (I swear I am not making this up) macho “pollen jocks” whose nectar-gathering intrepidity attracts admiring females, and pollen “fertilizes” plants in the same sense that farmers “fertilize” crops, acting as magic plant food. (The year before there was an animated talking-animal comedy called Barnyard featuring male cows with udders. I shudder to think of the collective sex-ed IQ points lost by a generation of children watching these movies.)

Marian coda: “Fruit of the womb”; “seed of the woman”

In Catholic magisterial writing it is common at the end of a document to include a reflection on the Virgin Mary. Echoing that tradition, two additional linguistic notes:

Once seeds (or embryonic plants) form in the ovary of the flower, the ovary becomes becomes seed-bearing fruit, attracting hungry animals and thereby helping to disperse the seeds. Fruit thus functions to help complete the process of plant reproduction. In animal reproduction, on the other hand, “fruit” refers to the new individual formed by the union of seed and egg, as in the phrase “fruit of the womb” (e.g., Psalm 127:3).

Today the phrase “fruit of the womb” is perhaps most familiar from the Hail Mary prayer: “Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus.”9 In Christian belief, of course, this particular “fruit of the womb” did not result from a typical “union of seed and egg” event—and a scriptural hint of the unique nature of this conception has been seen by some commentators in an important “seed” verse in Genesis understood by Christians as the first prophecy of Christ (i.e., the protoevangelium or “first gospel”).

After Adam and Eve eat the forbidden fruit, God tells the serpent:

I will put enmity between you and the woman,

and between your seed and her seed;

he will strike your head,

and you will strike his heel.” (Genesis 3:15)

This can be read in various ways: mythically, as an etiology of hostility between snakes and humans; allegorically, as a metaphor for the struggle against evil, or between good and evil people; prophetically, pointing to the defeat of evil by a chosen “seed” or descendant of the woman.10 For Catholics, the passage ultimately points to Christ, and the “woman” is ultimately the Virgin Mary, whose Immaculate Conception and sinless life perfectly exemplify “enmity” with the serpent, which represents Satan.

In this light, the phrase “seed of the woman” is striking in part because the word “seed” (Hebrew זֶרַע, zera; LXX Greek σπέρματός, spermatos), while it can mean “descendant,” often refers to the male principle of generation. Thus, a Child conceived without the normal male contribution may be considered, in a special way, the “seed of the woman.”11

Read more: Sex and death: Entomological fun facts! >

The kind of eggs, that is, the price of which played such a notable role in the rhetoric in the most recent election. And which, of course, continue to rise in price, and are projected to do so for the rest of the year, nyuk nyuk nyuk.

De rigueur caveat: I write regarding many topics as an interested student, not an expert; I am not a botanist, and as always I welcome input from anyone who knows more than I do!

Among flowering species, some are likewise made up of individual plants that are either male or female, while the members of other species are hermaphroditic. Obviously all plants that grow hermaphroditic flowers are themselves hermaphrodites, but not all hermaphroditic species grow hermaphroditic flowers; in some species, individual plants grow both male and female flowers.

This model of understanding male and female contributions to procreation was widespread in the ancient world, but not universal, as my friend Peter T. Chattaway (Thoughts and Spoilers) points out in the comments. As Peter notes, it was not unknown in the ancient world women have internal organs analogous to testes, and menstrual blood was thought by some to have some kind of reproductive significance (e.g., a female counterpart to semen). One rabbinic theory, based on Genesis 46:15 referring to “the sons of Leah” and “the daughter of Jacob,” was that fathers produce seed for female offspring and mothers produce seed for male offspring! I am not aware, though, of any premodern theory of reproduction that posits the union of male and female “seed” as the basis for every human or mammalian life.

The mammalian ovum was discovered in 1827 by the pioneering Prussian-Estonian embryologist Karl Ernst von Baer.

The function of pollen grains carrying male gametes, meaning that they, not seeds, are the vegetative analogue to animal “sperm,” likewise would not be understood until the 19th century.

While St. Thomas wrongly deferred to “the Philosopher” in his understanding of the begetting of women, Thomas’s dependence on scripture led him to mitigate Aristotle’s errors in certain ways. (For example, St. Thomas maintained that both men and women were intended by God in the order of creation and that both men and women would retain their sex in eternal life.) Still, like many Christian thinkers through the centuries, he did consider women inferior to men in a number of ways, and the impact of this patriarchal ideology has deformed Christian thinking and too often diminished the status of women down to the present day.

This line is adapted from Elizabeth’s greeting to the Virgin Mary at the Visitation (Luke 1:42).

According to the Ignatius Catholic Study Bible, “At least one Jewish tradition connects this triumph with the coming of a messianic king (Palestinian Targum).”

This is at best a suggestive connection; see similar language used in Genesis 16:10 for the female slave Hagar’s descendants.

Re: "The existence of vegetative eggs and mammalian eggs, and the equal hereditary contributions of mothers as well as fathers, though, was unknown until modern times."

Not so!

Well, okay, not *quite*. The ancients did not know about microscopic ova, true, but at least some of them *did* know about ovaries -- which were called "testes" by the Greeks -- and of course they knew about menstrual blood, which was thought by some to be a female kind of semen.

This is reflected in the Bible itself, when Hebrews 11:11 says Sarah, by faith, had a "seminal emission" (Greek: katabole spermatos) in her old age.

Also, the Hebrew grammar in Leviticus 12:2 seems to indicate that women produce seed -- and at least some of the Talmudic rabbis argued that Genesis 46:15 makes a distinction between "the sons of Leah" and "the daughter of Jacob" because each parent's seed produced children of the opposite sex, and it all came down to whose semen was emitted *first*.

Various Greek and Latin writers also held that a woman's seed could determine the sex of the child, depending on the temperature in the uterus, or whose semen was most abundant during sex, etc., etc.

I first learned about all this 33 years ago via an article in Bible Review that is currently available online here (but is probably behind a paywall): https://library.biblicalarchaeology.org/article/did-sarah-have-a-seminal-emission/

Hate to use a comment for this! Grammar touch-up needed: "In Catholic magisterial writing is is common". :-)