Christianity as an interpretation of history

[LONGREAD: Judaism, Jesus, and the mouse that roared]

“What is Christianity?” is a question that can be answered many ways. In a January post I gave an 11-word summary of Christian belief originally written for Twitter: “God became human to unite humans to God and one another.” I also wrote a lengthier description ending with the sentence “Being Christian is the soul’s response to the encounter with divine love in Jesus, moving us to love of God and love of neighbor.”

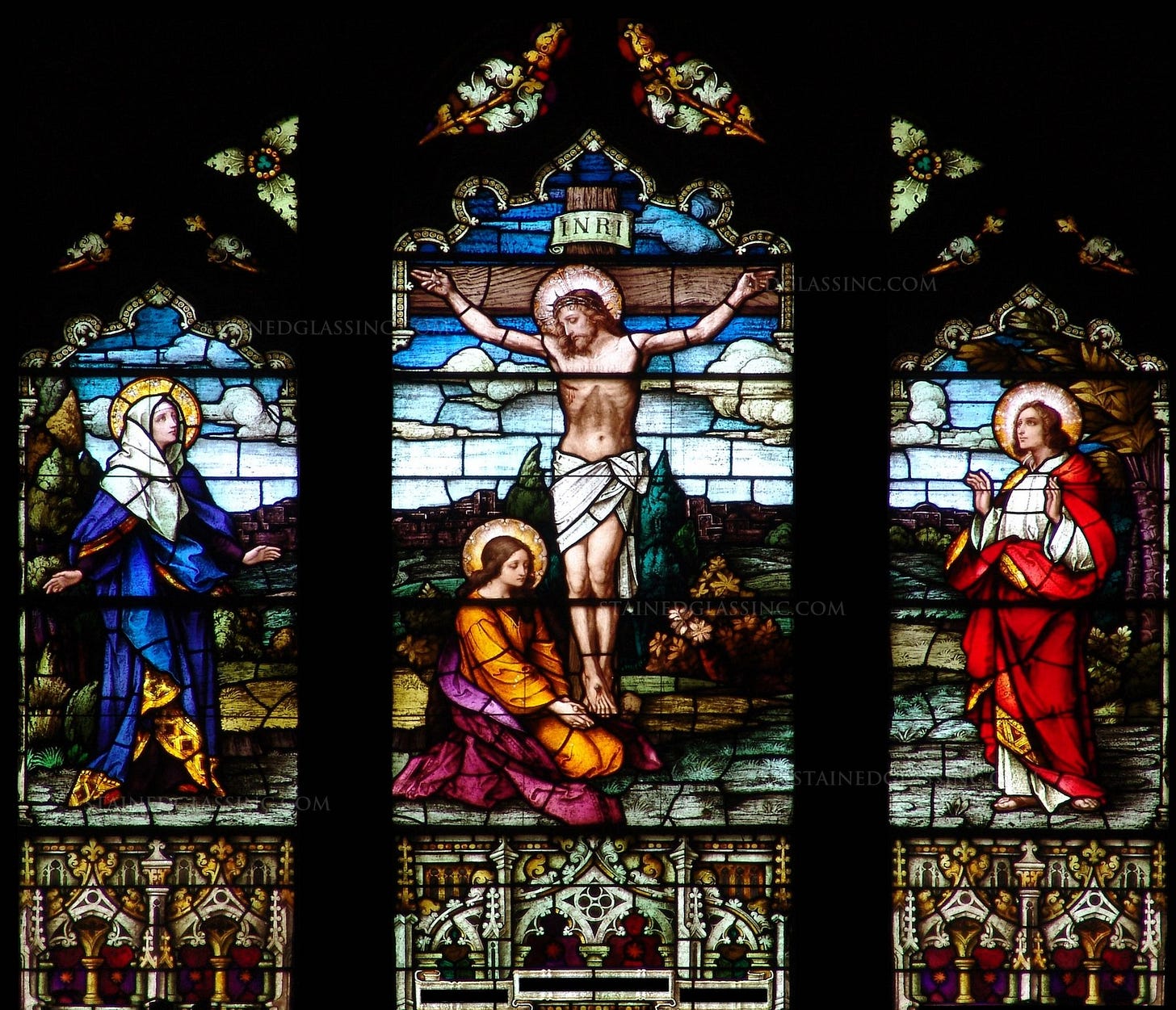

On another level, Christianity can be understood as an interpretation of history. In particular, Christianity can be understood most centrally as an interpretation of a brief and obscure chapter in history: the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth. Yet this chapter cannot be considered in isolation, apart from the preceding history of the Israelites and the subsequent history of the early church.

Even to speak of the resurrection of Jesus is, of course, already to offer an interpretation of the data around Jesus’ death and its aftermath: i.e., the interpretation that, after his crucifixion, Jesus really came to life again. What is not so often noted is that to reason from the proposition “Jesus came to life again” to the proposition “Christianity is true” is also an interpretation. Christian apologists and philosophers—and non-Christians for that matter—sometimes tend to approach the question of the resurrection as if the questions “Was Jesus raised from the dead?” and “Is Christianity true?” were equivalent. Philosophically speaking, the issue is more complicated than that. The questions are obviously related, but they aren’t equivalent.

If this sounds counterintuitive, ask yourself: Would it entail a logical contradiction to propose both that a) Jesus was raised from the dead and that b) Christianity is not true? I can’t see that it would. For example, suppose someone were to speculate that Jesus could have been restored to life by advanced extraterrestrial medical nanotechnology. Would that constitute an affirmation of the truth of Christianity? Obviously not. When Christians think about evidence around the question of the resurrection, it is generally with an implicit assumption that if Jesus was raised from the dead, this was done by divine power as the crowning achievement of Jesus’ divine mission on earth. Yet other interpretations could be proposed without logical contradiction.

Less whimsically, fans of Descartes might propose that Jesus could have been supernaturally brought to life, not by the all-powerful, benevolent deity of monotheistic faith, but by a powerful malicious spirit messing with humanity. It might even be argued that Jesus was raised from the dead by God’s power, but that God is so mysterious and unknowable that we cannot validly construe anything about his intentions or wishes from this fact.1

Certainly I would argue that the supposition that if Jesus was raised from the dead, this was done by divine power as the crowning achievement of Jesus’ divine mission on earth is a reasonable interpretive framework. Indeed, it seems to me so far the most reasonable interpretive framework that I imagine many atheists might agree in principle. But an interpretive framework it is.

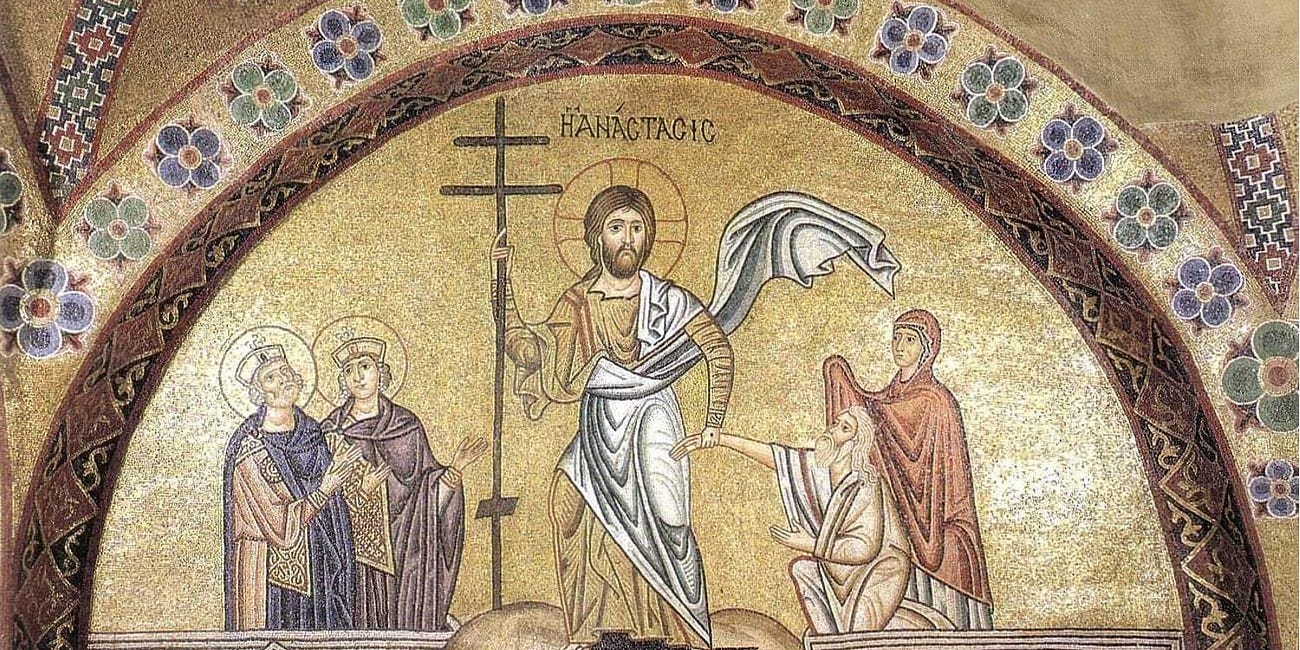

To accept Christianity is to see, not just in Jesus’ resurrection but in his entire life and teachings and in his death by crucifixion, actions of the mysterious and transcendent Creator of the universe involving himself in human affairs, accomplishing something on behalf of the human race. Among other things, Christians understand the Creator to be communicating with us in the person of Jesus, revealing himself to us, in a unique and definitive way, as well as acting in a decisive way for our ultimate benefit.

This interpretation, in turn, implies a larger proposition: namely, that, long before Jesus was born, the Creator was already communicating with and guiding humanity in a unique way through the history and religious experiences and development of the Israelites—and that his communication with humanity continues in the history of the early church.

Nothing in this proposition implies that the Creator has been entirely silent elsewhere, or that other cultures had no knowledge or inkling of the Creator and his ways. Nor does it imply that the religious ideas and experiences of the Hebrew people were of sheerly divine origin and totally sui generis, as if God started from scratch with a cultural blank slate and simply dropped pearls from heaven unmediated by human experience or culture. (How could anyone understand such pearls? Or, if they did, how could they understand anything else? Questions for further consideration in a future post.)

This idea of divine self-disclosure can be compared to a process of pedagogy, to teaching in stages and by degrees. The Israelite people were one ancient Near Eastern people among many, but in certain notable ways they stood out from surrounding cultures—and in these unique facets of the Hebrew experience Christians find signs of the Creator guiding and forming the religious consciousness of this people in a particular direction.

For example, there are hints in the Bible that Israelite religious imagination had not always been strictly monotheistic. Deuteronomy 32:8–9 can be understood as depicting Israel’s deity YHWH as head of a heavenly pantheon assigning other gods to other nations while reserving Israel for himself. Psalm 74:13–14 appears to imagine YHWH battling cosmic powers in a primordial struggle more akin to the Babylonian Enuma Elish than Genesis 1.

Yet, unlike other ancient Near Eastern deities, Israel’s deity was never one figure among many in some pantheon in which each had their own area of competence. Where the peoples of other nations had deities associated with wind and rain, seas and rivers, battles, sexuality and reproduction, death and the underworld, and so forth, and appealed to each of them in turn for whatever was needful at the moment, the deity of the Hebrews was always a jealous deity, demanding the loyalty of his people to him alone.

Even when Israelite religious imagination was not strictly monotheistic, only one was to be worshiped, the greatest of them all. This is sometimes called henotheism, but that is imprecise; henotheistic worship is devoted to a supreme deity without excluding worship of lesser deities. A better term here is monolatry: worship of one deity only among others who are not to be worshiped.

Monotheistic impulses arose elsewhere, notably in Egypt in connection with the cult of Aton (the sun) and in Persia among the disciples of Zoroaster who worshiped Ahura Mazda. Christians are free to interpret these impulses as real echoes of the voice of God among the peoples of the world. Yet in these other contexts the monotheistic impulse was always going against the grain of polytheistic religious tradition and culture, and never took root in a culturally transformative way.

In Egypt, the cult of Aton briefly rebelled against traditional Egyptian religion, but was just as quickly crushed. Zoroaster’s teaching won adherents mostly among the Persian aristocracy, and even in the Persian court it seems his influence was limited, and other deities apparently made a comeback. Again, many ancient Near Eastern pantheons did have some notion of a high god over all the others—but such a high god was generally imagined as distant, remote, unknowable in his transcendence. It was to lesser, local, more immanent deities that the peoples of the world offered their worship and turned with their needs.

Among the Israelites, by contrast, the monotheistic impulse met no such resistance; the prophets who proclaimed that YHWH was the only deity had a clearer path. As the historian William H. McNeill notes, “No other people in the Middle East could become monotheists and also remain true to their traditional faith, for they had all inherited polytheistic pantheons.”2 Israel alone had not.

With increasing clarity, the Israelites came to hold that their nation’s particular covenant deity was not only the greatest of all deities of all nations, but was in the fact the transcendent deity of the whole cosmos, the creator and true lord of all nations, and the gods of other nations were nothing. For this nation alone the most transcendent was not remote and unknowable, but was immanent in his covenant relationship with his people.

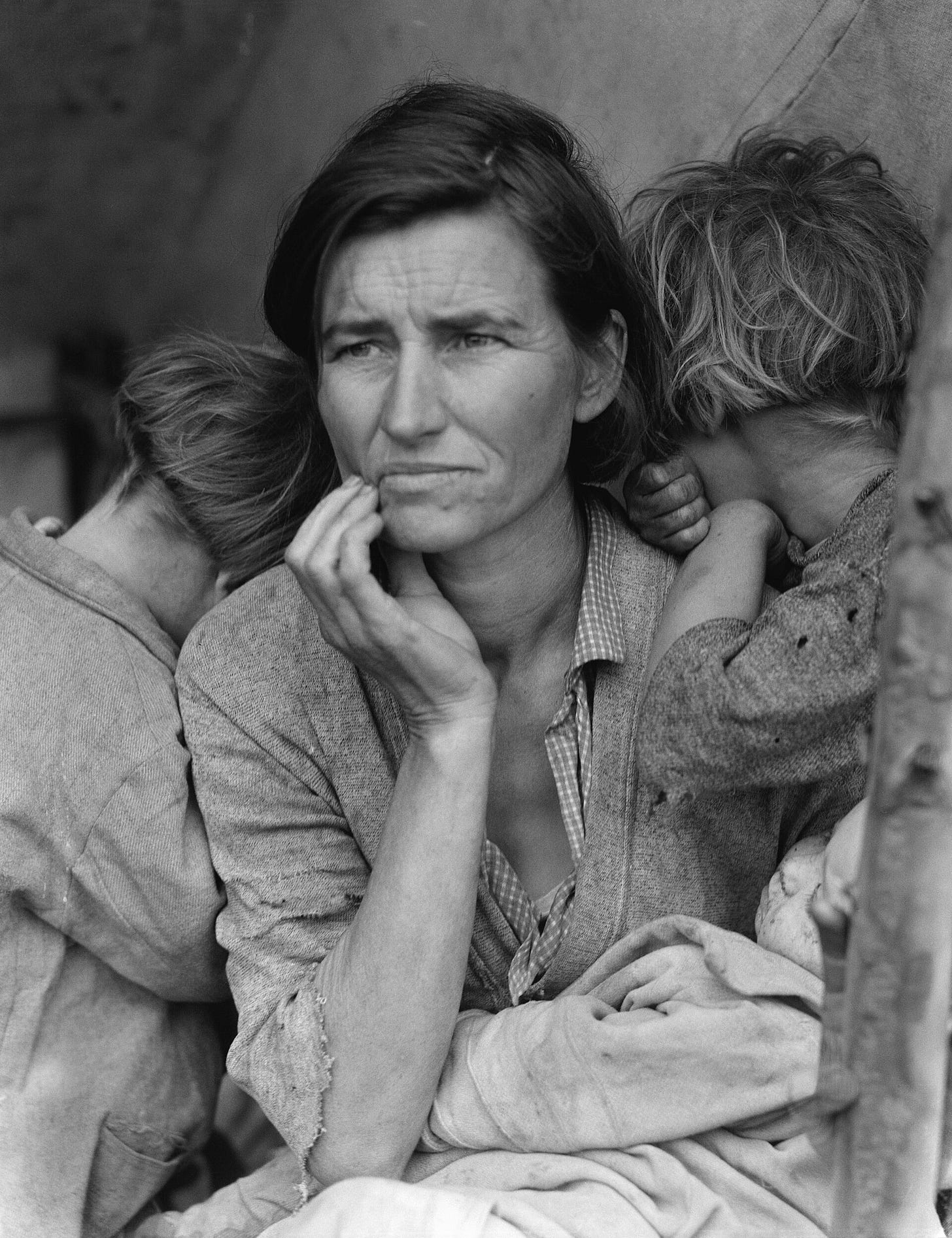

This unique religious heritage cleared the way for other developments. Under the influence of Israel’s prophets, the cult of YHWH became an ethical monotheism, with a striking and unique concern for calling the wealthy and powerful to task regarding the plight of the poor and powerless, especially in regard to oppression of the latter by the former.3

Western civilization has been so profoundly shaped by this motif in the Old Testament that it is very easy not to appreciate how extraordinary it is in its historical context. An important function of the literatures of other ancient cultures was to certify the power and authority of the established elites, especially priests and princes. To praise the mystic powers of the clerics, to flatter kings and courtiers with their greatness, was the normal thing for ancient poets and scribes. There was not a lot of call for vindicating the rights of foreigners, widows, and orphans, or for blasting the wealthy and powerful for their sins.

Even when the corruption and cruelty of Gentile elites reached such enormities as to elicit condemnation, the marginal were not therefore given great attention. It’s been noted that while “casting down the mighty from their thrones” is a motif that does crop up in ancient literature outside the Bible, “lifting up the meek and the lowly” is a much odder and less familiar theme.4

To accept Christianity is to see in this and other Old Testament themes the transcendent Creator of the universe guiding one particular people into a growing moral and spiritual awareness and an ever-deeper understanding of himself, a progressive pedagogy or education becoming a gradually increasing light amid the darkness of a fallen world. (The word “education” is derived from Latin for “to lead out” [e-ducere]. Think of Plato’s cave: All pedagogy is a progressive leading-out from darkness into light, from ignorance to knowledge, from simplicity to sophistication.)

And here we come to a crucial twist in the story: Among the Jewish people it became increasingly clear that the divine light that had been given to them was not for them alone. The day would come when YHWH would not only vindicate Israel before all the goyim, the nations of the world, but would reveal himself to the nations and call them to himself. Zion would become the highest of all the world’s mountains; all the kings of the earth would come to Israel to learn the wisdom of God. Not only in Israel, but in every nation men would exchange idols for the living God. The God of Abraham would be worshiped in every land.

This was such an extraordinary expectation that on one level it appears almost comically hubristic. Israel was a nation with a great religious vision, but they were not great among the power players of the ancient Near East. On the contrary, they were dominated by one conqueror after another. The notion of Egypt turning from Ra and Isis and Osiris, Greece from Zeus and Athena and Apollo, Rome from Jupiter and Diana and Mars, to worship the covenant deity of a comparatively marginal backwater people was…improbable, to say the least.

This subject has long put me in mind of the 1959 Peter Sellers comedy The Mouse that Roared, about a tiny European state called the Duchy of Grand Fenwick that absurdly declares war on the United States, fully intending to surrender and then reap the benefits of America’s generosity in rebuilding the economies of its defeated enemies. The great twist, which could only happen in a comedy, is that Grand Fenwick somehow wins the war.

But imagine that instead of merely declaring war on the United States, Grand Fenwick had also declared war on all their European neighbors as well: Germany, Italy, France, Spain, the UK, everyone. And suppose that instead of planning to surrender, they honestly thought they were going to win. Such a scenario would be not entirely unlike the ancient Jewish people surveying their far more powerful neighbors and conquerors and confidently declaring, “Yeah. All-y’all are going to turn from your false gods and worship the God of Abraham.”

Yet this hope, however seemingly absurd, did not simply come to nothing. On the contrary, within decades of the death of an obscure Galilean rabbi and prophet named Jesus of Nazareth, Abraham’s covenant deity was being worshiped in Gentile cities—not just by Jews in diaspora, nor by individual Gentile converts to Judaism, but by entire communities of Gentile Christians—in Asia Minor, northern Africa, Damascus, Greece, and elsewhere. By the second century the Christian faith had spread all over the known world; by the end of the second century Tertullian famously boasted to his pagan readers:

We are of yesterday, and yet we have filled all your places; your cities, islands, villages, townships, assemblies, your very camp, tribes, companies, palace, senate, forum; we leave you only your temples. We can count your armies; the Christians of one province are more numerous.5

All the more remarkably, in contrast to the later spread of Islam—which also, in its own way, proclaimed the God of Abraham—early Christianity spread like wildfire without political support or military backing. This changed, of course, in the fourth century after Constantine legalized Christianity in 313, and still more after his successor Theodosius made Christianity the official religion of the Roman empire in 380.6 Yet Jesus and the apostles fought no battles. The fathers, apologists, theologians and evangelists of the first three centuries commanded no legions, conquered no cities, and governed no subjects. On the contrary, early Christianity was widely regarded as a religion of the powerless, of the poor, workers, slaves, women, and so forth.

I don’t cite any of this as “proof” of anything necessarily miraculous in the spread of early Christianity. Miracles, by their nature, cannot be proven; that a miracle has occurred is always a matter of interpretation, not proof—and this is the case whether by “miracle” one understands the post-Enlightenment concept of a “suspension of the laws of nature” or the biblical sense of a dramatic sign of God’s power and intentions in the world.7

One can certainly consider and examine the spread of early Christianity (and later Islam) within the framework of historical cause and effect.8 To accept Christianity is not to say that the events outlined above “prove” that Christianity is true, or that the events in question are otherwise inexplicable. It is to see in these events a meaningful pattern or movement in which the intentions and will of the Creator of the universe are revealed in human history.

To accept Christianity is to look at what was unique in the history, culture, and religious consciousness of the Jewish people that made for the shaping of a culture founded upon ethical monotheism, that elicited such a strident tradition of speaking truth to power while lavishing solicitude on foreigners, widows, and orphans, that regarded the manmade gods of the goyim with contempt while anticipating the revelation of Israel’s God to the benighted pagans, and also at what was unique in the singular career and teaching of Jesus of Nazareth (again, this is the central chapter, but it’s also just a few short years in a long history, and needs to be explored on foot and not at 20,000 feet), and at what was unique in the spread and development of early Christianity, and to see in all of this a story being told by the Creator of the universe.

To accept Christianity is to see in this story, and especially in its central chapter and protagonist, a firm foundation for a way of thinking and acting, for a worldview and a life well lived. It is to see in Jesus, in all his paradoxical blend of gentleness and sternness, of alarming moral rigor and uncompromising ethic of forgiveness, of welcome to outcasts and the marginalized and of withering critique of the religious elites, a mirror—the mirror—of the face of God.

It is to proceed trusting that the enigmatic, unknowable Creator of the universe who dwells in unapproachable light can be approached on this basis: that in Jesus and in the Christian faith we have a means of knowing and seeking God, and, in so doing, can enjoy confident hope of finding our ultimate good and our true fulfillment, beginning in this life and finally in the life to come.

What I have said here is of course not a sufficient account of what Christianity is. As a philosophical way of framing what it means to accept Christian faith, though, I find this a helpful place to begin.

More God thoughts >

More Catholic thoughts >

More longreads >

See also

What is a miracle? It depends partly on interpretation.

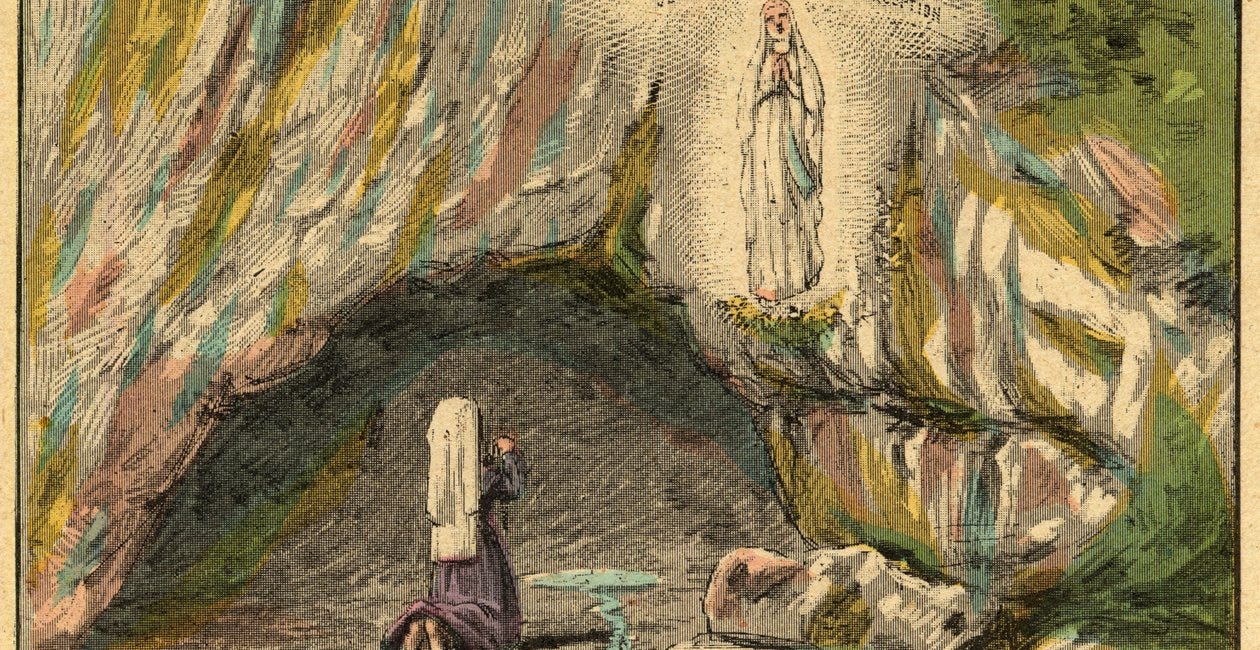

Today, 16 April, is usually the memorial of St. Bernadette Soubirous, who died on this date 146 years ago. (She was beatified 100 years ago in 1925 by Pope Pius XI, who also canonized her eight years later in 1933.) This year her memorial is superseded by Wednesday of Holy Week…

A religious epistemic hierarchy: What I believe in 18 theses, ranked

This is a follow-up of sorts to last week’s reflections on reason and faith. For some time I’ve been mulling over the notion of trying to organize my religious beliefs in a some kind of epistemic hierarchy or ranking. That is, as a Catholic Christian, what is most foundational to me …

In my essay “Faith, Reason, and Interpretation: Belief and Doubt in The Song of Bernadette and Lourdes” in Film as an Expression of Spirituality: The Arts and Faith Top 100 Films (2023, Cambridge Scholars), edited by Kenneth R. Morefield (and excerpted in a January post), I proposed the following taxonomy of “hypothetical wonder-working agencies other than a benevolent deity”: Such agencies, I wrote,

can include any of several types of what can collectively be called magic: those involving paranormal principles or energies inherent in the natural world (sometimes called mana, a term taken from Melanesian and Polynesian cultures); those involving paranormal human abilities (psychic powers); and those involving non-divine or malicious spirits, whether preternatural (demon-like) or natural/animistic (sprite-like), acting either independently or at the behest of magician-like human agents. Superadvanced technology (such as might be used by extraterrestrials or time travelers) would be yet another sort of “magic,” per Clarke’s third law (“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”). Prodigies might also be accounted for on world-denying scenarios like the simulation hypothesis or a variation on Descartes’ “evil genius” thought experiment. (This last would be conceptually distinct both from preternatural demon-like magic, which implies an independently existing natural order, and from miracles, which implies a benevolent power.) Malicious powers might be conceived as having ulterior motives for allowing occasional extraordinary healings (e.g., fostering futile faith in God…).

William Hardy McNeill, A World History (Oxford University Press, 1979), 71.

See McNeill, 67–72.

For some discussion of the exceptionality of concern for the poor and marginal in the Hebrew prophetic tradition, see Rabbi Harold M. Schulweis’s discussion of the work of Rabbi Abraham Heschel in “The Prophet” (Jewish Journal).

It is often incorrectly claimed that Constantine made Christianity the official religion of Rome. In fact, Constantine’s 313 Edict of Milan merely granted Christianity legal status and freedom from persecution. 77 years later, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman empire under Theodosius.

For more, see “What is a miracle? It depends partly on interpretation.”

For a range of academic commentary on the appeal of early Christianity and why it spread, see “The Great Appeal: What did Christianity offer its believers that made it worth social estrangement, hostility from neighbors, and possible persecution?” (PBS.org).

![“Ecce homo” [Behold the man] (Antonio Ciseri, ca. 1860–1880) “Ecce homo” [Behold the man] (Antonio Ciseri, ca. 1860–1880)](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6NN8!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1caa73d6-ac2d-467f-8498-d501a1d1f3c0_1500x820.jpeg)

I found many of your points enlightening. One tiny correction: e-ducere is Latin, not Greek

But our current crisis impacts on your discussion. We have now become very acquainted with narcissism. Perhaps the Hebrew conviction that their tiny religion would attract all the gentiles can be viewed as narcissistic--the ultimate chutzpah. We now know all too well the vulnerability of the human mind to malignant narcissism.

This is a beautiful piece. I say that as an Orthodox Jew. I think you understand the monotheistic impulse of Judaism perfectly.

And you quote the mouse that roared!

Many Christians have trouble understanding why exactly Jews do not accept Jesus as a Messiah. There are a number of reasons. The usual one advanced is that God promised in Deuteronomy the commandments would never be abrogated and that the Jews would never be replaced. But of course, many interpretations of Christianity still require Jews to keep the commandments and avoid replacement theology. So that is not the sole reason.

The main reason is actually what makes Christianity Christian, which is that Jews cannot accept that a Monotheistic God placed himself inside a body, seemingly in violation of the first two of the ten commandments. It is this rejection of the omniscient monotheistic impulse that Judaism has an issue with, and if there would be an interpretation of Christianity where Jesus was a messenger or God but not God himself that would be fully compatible with Judaism.

Great post!