What is a miracle? It depends partly on interpretation.

[LONGREAD: excerpt from an essay on faith, reason, and interpretation]

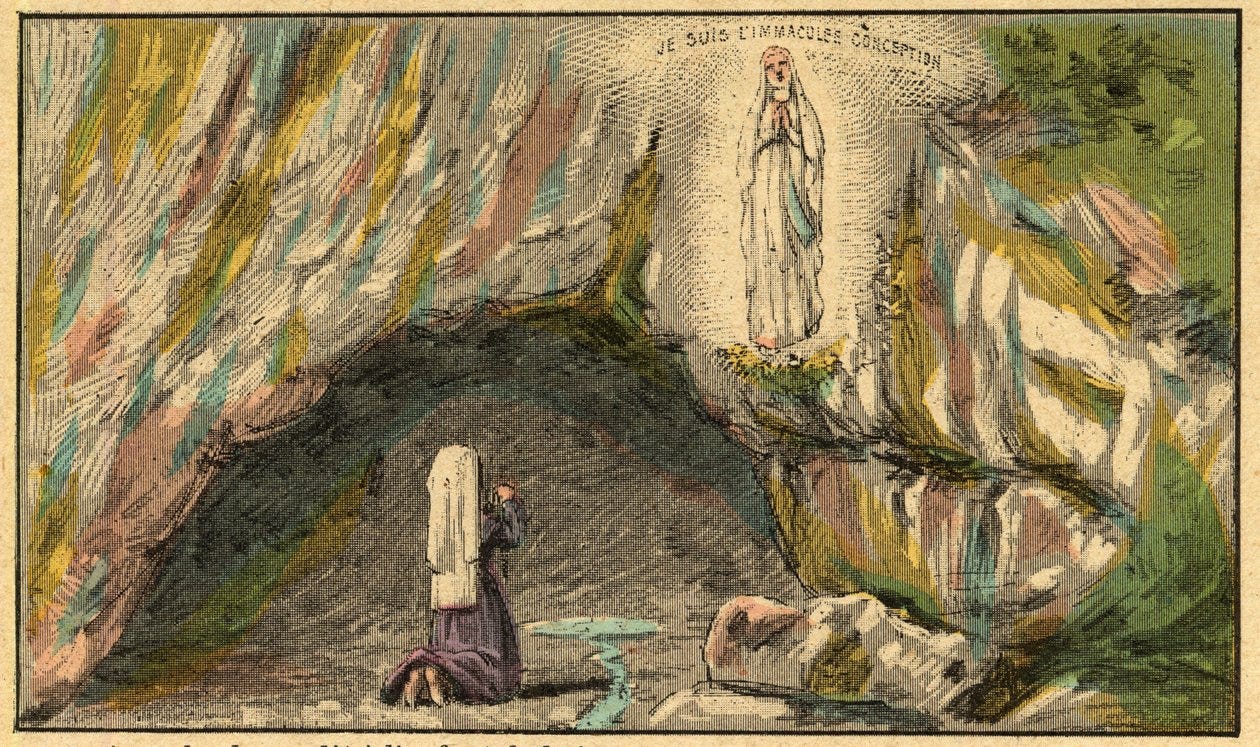

Today, 16 April, is usually the memorial of St. Bernadette Soubirous, who died on this date 146 years ago. (She was beatified 100 years ago in 1925 by Pope Pius XI, who also canonized her eight years later in 1933.) This year her memorial is superseded by Wednesday of Holy Week (“Spy Wednesday,” as it’s sometimes called), but this isn’t really a post about Bernadette.

Instead, I thought I would take the occasion of the date to post something I’ve wanted to share for awhile: an excerpt from my essay “Faith, Reason, and Interpretation: Belief and Doubt in The Song of Bernadette and Lourdes” in Film as an Expression of Spirituality: The Arts and Faith Top 100 Films (Cambridge Scholars, 2023), edited by Kenneth R. Morefield.

This essay—one of the five things I’ve written of which I am the proudest—discusses questions of faith and interpretation in the context of two films relating to the Lourdes phenomena: Henry King’s The Song of Bernadette (1943) and Jessica Hausner’s Lourdes (2009). (I’ve previously posted a video conversation with Morefield about the two films, my essay, and the Arts and Faith Top 100 Films list.)

In this excerpt I’m writing in an academic mode, not about the movies or the Lourdes phenomenon, but about the concept of miracles generally and on the relationship between miracles and interpretation. (For this post I’ve very slightly adapted the essay, e.g., removing a passing reference to events in one of the movies, adding hyperlinks where appropriate, changing inline citations of modern works to footnotes, etc. Existing footnotes are retained.)

If you find the excerpt interesting, I hope you’ll seek out the book and the full essay!

The word “miracle” in both English and French comes from the Latin miraculum, meaning an object of wonder. In Christian culture the word corresponds to concepts found in the Bible represented by various Hebrew and Greek terms with senses including “mighty work,” “wonder,” and “sign.” This general set of ideas remained prevalent in the patristic era, with Augustine relating these ideas in the following way: The “mighty work” of the miracle inspires “wonder” in witnesses, thereby emphasizing the “sign” or message. For Augustine, what matters most is the sign value or signification of the miracle, which the experience of wonder serves to illuminate and emphasize—as people would value more the divine name written in gold than in ink, Augustine says, though the meaning is the same (On the Trinity III, 10). Later scholastic theology tended to emphasize divine causality (the “mighty work” aspect) as the essence of a miracle. For Thomas Aquinas, a miracle implies that “something is done outside the order of nature”—a criterion he takes so strictly that even the paranormal actions of angels and demons, who belong to the created order, are not to be accounted miracles (Summa Theologiae I, 1, 4).

In the modern age miracles have often been thought of as events “contrary to the laws of nature.”1 The dominant sense of the English term today is well given in a definition used in a number of dictionaries from Oxford University Press: “A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divine agency.” Implicit in this definition is the idea of divine benevolence, as opposed to some other hypothetical paranormal agent.2 In biblical literature, and in a contemporary Catholic3 theological context, the semiological function of miracles, the sign function emphasized by Augustine, is essential: Miracles are understood to point beyond themselves, to function as divine self-communication, as part and parcel of divine revelation.4 In fact, according to Catholic theologian Karl Rahner, miracles are divinely intended to communicate a specific message to a specific audience; a miracle without a message or a recipient is a contradiction in terms.5

In other words, there is both an objective and a subjective dimension to the concept of miracles; to posit a miracle is to take a stance not only on what happened, but also on why it happened, on what it means. Even in the most favorable circumstances, then, empirical evidence can take us only so far with respect to proposed miracles. First of all, we must accept that something extraordinary and truly inexplicable has happened: a premise that a sufficiently determined skeptic can usually avoid if they wish. To take an extreme example, suppose that the raising of Lazarus occurred historically exactly as recorded in John 11. Almost no one in the crowd who witnessed it would have had certain knowledge that Lazarus had definitely been dead in the first place: He might have been in a deathlike coma; it could even have been an elaborately orchestrated hoax. But, secondly, even for those, like Mary and Martha, who did know that Lazarus was dead—even if we should witness the certifiably dead raised to life before our own eyes, as happens, for example, at the climax of Carl Dreyer’s 1955 Ordet—this would be empirical evidence only of an inexplicable prodigy, not a miracle. To call it a miracle is to exclude the possibility that the dead person has been restored to life by a paranormal agent other than a benevolent God,6 and this question can never be empirically resolved.

The move from “Something extraordinary and inexplicable appears to have occurred” to “I believe God is at work here” is necessarily both a leap of faith and an act of interpretation, a construction of meaning. If God does not exist, or if he either does not act in extraordinary ways in the world or at any rate is not active in the events in question, then such constructions of meaning are illusions comparable to pareidolia, like seeing faces in clouds. The method by which we construct meaning and form impressions of reality is mysterious, and our ideas and rationales for our beliefs are not always illuminating. John Henry Newman coined the term “illative sense” to describe the complex phenomena of conscious and unconscious processes by which one “gathers up the fragments of experience into a single and unified judgment.”7 Reason, intuition, life experience, desire, conscience, habit, and other factors both inform and are informed by the illative sense. Although it was the riddle of religious faith and disbelief that drove Newman to develop this epistemological concept, it embraces all human knowledge and experience, from interpreting another person’s behavior as a sign of anything from boredom to romantic interest to recognizing a shape on a tree branch as a squirrel.

Building upon Newman’s illative sense as well as Wittgenstein’s concept of “seeing-as,” John Hick proposes that all knowledge and awareness is an outcome of a process of interpretation, of fitting sense experiences into a meaningful framework. In Hick’s words, “all conscious experiencing … is ‘experiencing-as’.”8 Hick distinguishes three levels or realms of awareness or knowledge: the natural, the human, and the divine.9 To the first and lowest level, the natural order, belong judgments like “There’s a squirrel on that branch.” The second level, the world of human meaning, includes and builds upon the natural order while going beyond it. Specifically human judgments include interpretive statements10 like “Bernadette is just making up a story to feel important” and “She doesn’t seem very pious, our miracle girl”; they also include ethical or moral judgments like “Laughter wastes valuable time” and “You can’t just leave her!” Finally, building upon both of the first two levels, the divine realm includes such statements as “Christ founded the Church to teach, govern, sanctify, and save all men” and “God has sent us a powerful sign, a sign of his grace and his love.”

Mistaken interpretive judgments—a given state of affairs “experienced as” something quite different—are of course possible at any level. On the natural level, Hick points out that what looked at first like a squirrel might turn out to be an odd knobble on the branch.11 Misinterpretations of human behavior occur all the time. As for the divine sphere, if God exists, and if he is active in the world or in some way knowable to human beings, it may be all too likely that his actions and intentions are misunderstood more often than not—even if the illative sense contains, as Newman and Hick believe, some kind of sense or instinct for the divine. What is more, while misinterpretations on the natural level are often relatively easy to investigate and resolve, those on the human level can be trickier and sometimes resist any final resolution.12 As for interpretations embracing the divine realm, like statements about ethical obligations, they may sometimes be falsifiable, but never verifiable.13

Applying his religious epistemology to the topic of miracles, Hick writes that

a miracle, whatever else it may be, is an event through which we become vividly and immediately conscious of God as acting towards us. A startling happening, even if it should involve a suspension of natural law, does not constitute for us a miracle in the religious sense of the word if it fails to make us intensely aware of God’s presence. In order to be miraculous, an event must be experienced as religiously significant.14

Hick’s account of religious epistemology broadly distinguishes between religious interpretation of “our material environment: things, events and processes in the world” (including miracles) and inner religious or mystical experience.15 Of the two, Hick has a clear preference for the latter.16 Drawing upon Kant and Schleiermacher,17 Hick argues for the epistemic equivalence of religious experience in all religious traditions, leading to a form of religious pluralism essentially equivalent to religious indifferentism. Distinctions between Christianity and other religious traditions regarding doctrine, ritual, and claims of divine revelation, prophecy, and miracles distinctive to a particular religious tradition, Hick considers culturally relative trappings, of mythic or poetic significance at best.18 “As has often been pointed out, it is invariably a Catholic Christian who sees a vision of the Blessed Virgin Mary and a Vaishnavite Hindu who sees a vision of Krishna, not vice versa.”19 Furthermore, “secular historians discount miracle stories whilst religious historians tend to treat as veridical some at least of those accepted within their own tradition.”20

On this last point Hick overstates his case, or at least oversimplifies the reality. “Discount” can mean different things. Some miracle stories, from the parting of the Red Sea to the Virgin Birth, secular historians generally discount as myths or legends of no historiographical value. But others, from Jesus’ healing miracles and feeding of the multitudes to many of the healings at Lourdes, are by many secular historians not so much “discounted” as interpreted non-miraculously—and the grounds on which non-miraculous interpretations are advanced can be more philosophical than historical or evidential. As C.S. Lewis writes in a programmatic passage:

Many people think one can decide whether a miracle occurred in the past by examining the evidence ‘according to the ordinary rules of historical inquiry’. But the ordinary rules cannot be worked until we have decided whether miracles are possible, and if so, how probable they are. For if they are impossible, then no amount of historical evidence will convince us. If they are possible but immensely improbable, then only mathematically demonstrative evidence will convince us: and since history never provides that degree of evidence for any event, history can never convince us that a miracle occurred. If, on the other hand, miracles are not intrinsically improbable, then the existing evidence will be sufficient to convince us that quite a number of miracles have occurred.21

An instructive example is a purported miracle associated with another modern-day Marian apparition: the “Miracle of the Sun” at Fátima on October 13, 1917. A month earlier, three shepherd children who had reported monthly appearances of the Blessed Virgin starting in May of that year stated that the Virgin Mary had promised a miracle on that day “so that all my believe in my apparitions.” The prophecy was widely publicized, and on the promised day a crowd of tens of thousands had gathered, including devout Catholics and skeptics, journalists and scientists.

Eyewitness reports from the crowd as well as from people as far as 25 miles away describe seeing the sun shining in various colors reflected on the clouds and surroundings; some also reported seeing it spinning, growing larger, or plunging to earth before resuming its normal appearance—phenomena that were “experienced as” miraculous by countless witnesses, while others present interpreted it differently. The reports were sufficiently persuasive to persuade many secular commentators that some remarkable atmospheric or meteorological phenomenon must have occurred, and a wide range of varyingly unusual conditions, or combinations of conditions, have been proposed to explain it. Yet the divergence of eyewitness reports, combined with the promise of a miracle on that day, incline others to chalk it up to mass hysteria or some other self-fulfilling mechanism.

Splitting the difference somewhat, Catholic priest and physicist Rev. Stanley L. Jaki has proposed that the phenomenon itself may have been naturalistic in whole or in part—a freak convergence of atmospheric conditions—yet the timing of this freak convergence at noon on the very day that a prophesied miracle had gathered tens of thousands he finds to be unavoidably meaningful, a sign from heaven.22 Notably, this interpretation effectively moots a distinction between “direct” and “indirect” divine actions; or, in other words, between miracles in the Thomistic sense, which are strictly impossible in natural terms, and extraordinary outcomes that are not strictly inexplicable in scientific terms but which are nevertheless of such a character that the kind of explanation provided by natural or scientific laws will be widely felt to be insufficient and which are ascribed to a mode of divine operation sometimes called providence.

Assuming the extraordinary phenomena over Fátima was meteorological in nature, there was obviously no natural way the children could have known ahead of time that the conditions at that spot would be right for such a thing on that date. Extraordinary coincidences do occur, but typically in contexts described by the “law of truly large numbers,”23 which include countless less noticed “misses” for every striking “hit.” In this case, well-publicized, ongoing apparitions gathering large crowds comparable to Lourdes and Fátima were not common at that time; of these, I cannot find a single prior case involving a well-publicized prophecy bringing together a vast crowd with a promise of a clear, dramatic sign on a specific day.24

And that’s it for the excerpt! Hope you enjoyed it.

Since it’s Holy Week, let’s briefly consider the resurrection of Jesus in light of my argument about miracles and interpretation. N.T. Wright, in The Resurrection of the Son of God, argues the following:

That the early Christians believed that Jesus was physically raised from the dead can reasonably be proposed as a datum of history. (Of course, like all historical data, this is already an interpretation of evidence.)

This belief is presented in the New Testament in connection with two pieces of evidence: After the crucifixion, Jesus was laid in a tomb that was later found empty, and many people experienced encounters with Jesus.

Wright argues that these two circumstances together—both the empty tomb and the post-crucifixion experiences of Jesus—are the necessary and sufficient historical explanation for the belief in Jesus’ resurrection. An empty tomb by itself, Wright contends, would be understood (as Mary Magdalene initially assumes in John 20) as evidence that the corpse had been moved, while enounters with Jesus after his crucifixion, in the absence of a missing body, would naturally be understood as a vision or spiritual experience, not a physical resurrection.

Thus, Wright proposes that the historical evidence suggests both that Jesus’ body really did go missing from the tomb where he was laid, and that many people really did have experiences of Jesus after his crucifixion. It does not follow necessarily from these two proposed facts that Jesus was really raised from the dead. But Wright argues that the premise that Jesus was raised from the dead best explains the empty tomb and the encounters with Jesus.

Yet even if we accept that Jesus was raised from the dead, it does not directly follow that this mysterious, inexplicable event directly establishes that Christianity is true. It does not follow that Jesus is the Son of God, that he was raised from the dead by God’s power, or that he was raised from the dead to accomplish or communicate anything on behalf of humanity. To say that Jesus was raised from the dead is to offer an extraordinary explanation for extraordinary historical data; to say that Jesus was raised from the dead by God for our salvation is an interpretation of the data, a construction of meaning. It is a reasonable interpretation, I believe.

If you want to read the whole essay, here’s the book again.

Also related:

Watch: ‘The Song of Bernadette’ and ‘Lourdes’ – An Arts & Faith Top 100 discussion with Kenneth R. Morefield

For many years, artsandfaith.com was a discussion board hosting a lively online community with a lot of passion for movies and other art forms, among other topics. Many of the regular participants were Chris…

David Hume, “On Miracles.” Concerning Human Understanding, section X, collected in The Philosophical Works of David Hume: Including All the Essays, and Exhibiting the More Important Alterations and Corrections in the Successive Editions Published by the Author; in Four Volumes, vol. 4 (Adamant Media Corp, 2007, pp. 88–99), 93.

Hypothetical wonder-working agencies other than a benevolent deity can include any of several types of what can collectively be called magic: those involving paranormal principles or energies inherent in the natural world (sometimes called mana, a term taken from Melanesian and Polynesian cultures); those involving paranormal human abilities (psychic powers); and those involving non-divine or malicious spirits, whether preternatural (demon-like) or natural/animistic (sprite-like), acting either independently or at the behest of magician-like human agents. Superadvanced technology (such as might be used by extraterrestrials or time travelers) would be yet another sort of “magic,” per Clarke’s third law (“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”). Prodigies might also be accounted for on world-denying scenarios like the simulation hypothesis or a variation on Descartes’ “evil genius” thought experiment. (This last would be conceptually distinct both from preternatural demon-like magic, which implies an independently existing natural order, and from miracles, which implies a benevolent power.) Malicious powers might be conceived as having ulterior motives for allowing occasional extraordinary healings (e.g., fostering futile faith in God, the Virgin Mary, and the cultus of Lourdes).

“Catholic” here and subsequently refers to theological ideas that substantially overlap with much non-Catholic Christian thought. Because of the diversity in Protestant thought in particular, I will sometimes focus on Catholic Christianity as the mode of Christian thought relevant to the phenomena associated with Lourdes, without intending to exclude non-Catholic Christian belief wherever applicable.

Rev. Fr. Casmir Ikechukwu Anozie, The Contemporary Catholic Theology of Miracles (2018 doctoral dissertation, John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Faculty of Theology), 9–12, 38–50, 64–65.

Ibid, 22.

On hypothetical paranormal agents other than a benevolent God, see note 2 above.

Aidan Nichols, A Grammar of Consent: The Existence of God in Christian Tradition (University of Notre Dame Press, 1991), 32.

John Hick, An Interpretation of Religion: Human Responses to the Transcendent (Macmillan, 1989), 140.

Ibid, 107.

Aside to Substack readers: The quotations that follow Substack are taken from the two movies discussed in the full essay.

Ibid, 140.

On the natural level, the question of the squirrel on a branch might be forever unanswerable if one sees the tree from a moving train. For that matter, questions about animal behavior and motives can invite interpretive challenges in some cases comparable in sophistication and complexity to questions about human behavior and motives, and potentially as unanswerable. Unanswerable questions about other people’s behavior and motives do tend to be more momentous, though. Still, a case could be made for splitting the natural world by level of complexity into mineral, vegetable, and animal, or at least into non-animal and animal, with the human world constructed on top of (and of course including) the animal.

As another critique or expansion of Hick’s levels, the human world might be split into a lower level of interpretive judgments about other people’s behavior and a higher level for ethical or moral judgments, which, like judgments about the divine realm, are inherently non-empirical and non-verifiable. In fact, there’s a fuzzy line between an ethical statement like “Based on available evidence, we are not morally justified in believing in God” and a divine-realm statement like “God probably doesn’t exist.”

Hick, God and the Universe of Faiths: Essays in the Philosophy of Religion (Springer, 1988), 51.

Hick, Interpretation, 140.

Avery Robert Dulles, Models of Revelation (Orbis Books, 2014), 70, 107; Christopher Sinkinson, The Nature of Christian Apologetics in Response to Religious Pluralism: An Analysis of the Contribution of John Hick. University of Bristol, 1997 doctoral dissertation), 210, 219–221.

Sinkinson, 76.

Dulles, 107–173; Sinkinson,153–159, 169–179.

Hick, Interpretation, 166.

Ibid, 364.

C.S. Lewis, Miracles (Collier Books, 1978), 3–4.

Stanley L. Jaki, God and the Sun at Fatima (Real View Books, 1999), 346–361.

David J. Hand, The Improbability Principle: Why Coincidences, Miracles, and Rare Events Happen Every Day (Macmillan, 2014), 83–116.

The vast majority of Marian apparitions reported in this time frame consisted of a single vision (not a series of apparitions). Most were not publicized, and many involved no message. A small number resembled Lourdes and Fátima in including a series of apparitions that were widely publicized and drew large crowds. Some Marian apparitions did include specific prophecies that were never publicized and were later refuted by history. For example, a dozen years before Lourdes, in 1846, two children in La Salette-Fallavaux in southeastern France (Our Lady of La Salette) reported a single appearance of a Lady who gave them, along with a message that was publicized, secret predictions that were reported to the pope via letter. At least some of these predictions manifestly did not come to pass (see Jimmy Akin and Dom Bettinelli. “La Salette Apparition,” Jimmy Akin’s Mysterious World, episode 60, StarQuest Media). However, because they were secret, there was no public test of the visionaries’ credibility as there was in Fátima on October 13, 1917.

This is (obviously) more in the realm of speculation and not something we can actually argue/prove, but I’ve long thought that the Fatima miracle makes the most sense either as a vision granted to a large group of people, or perhaps more likely a miraculous local manipulation/redirection of the incoming rays of light (i.e. in a way that could be theoretically recorded by a camera, in a way that a vision could not).

In any case, I’d wager it’s also the same “type” of miracle as the biblical account of the sun standing still for Joshua, which again seems to have been a “local” phenomenon, not actually globally reported in the way you’d expect if the celestial bodies were actually being manipulated in such a mind-numbingly massive manner.