Calvin & Hobbes Sunday: Do you want to build a snowman?

[silence speaks, part 2: a Cartoon Critic appreciation]

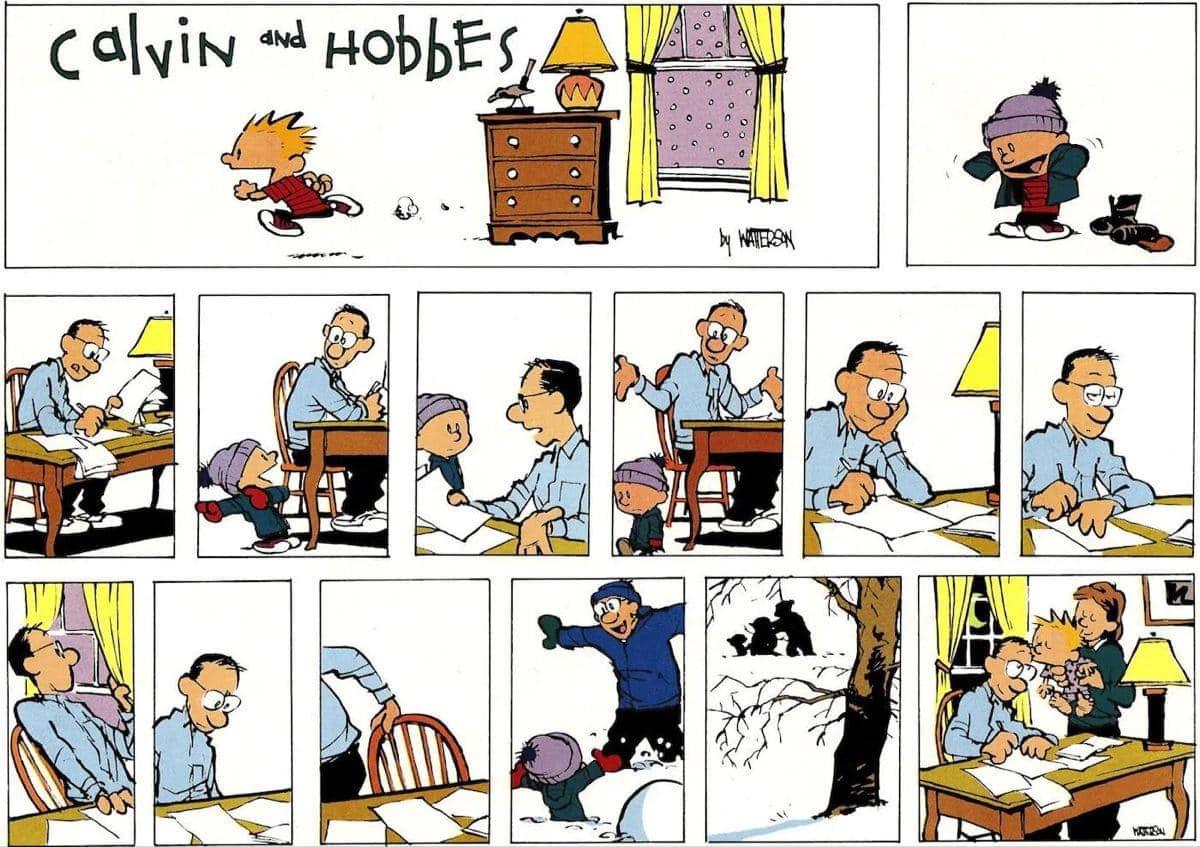

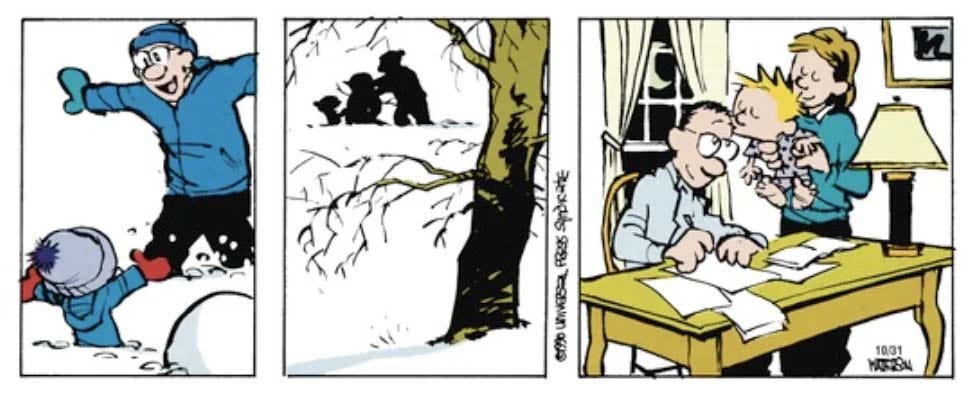

Today’s subject is a Calvin & Hobbes Sunday strip that’s justly beloved1 for a number of reasons, not least its rare heartwarming ending (a denouement a bit more complex than it may initially seem, as we will see). It dates to October 1990—almost exactly halfway through Bill Watterson’s brilliant ten-year career, which lasted from 1985 to 1995. Here’s the full strip:

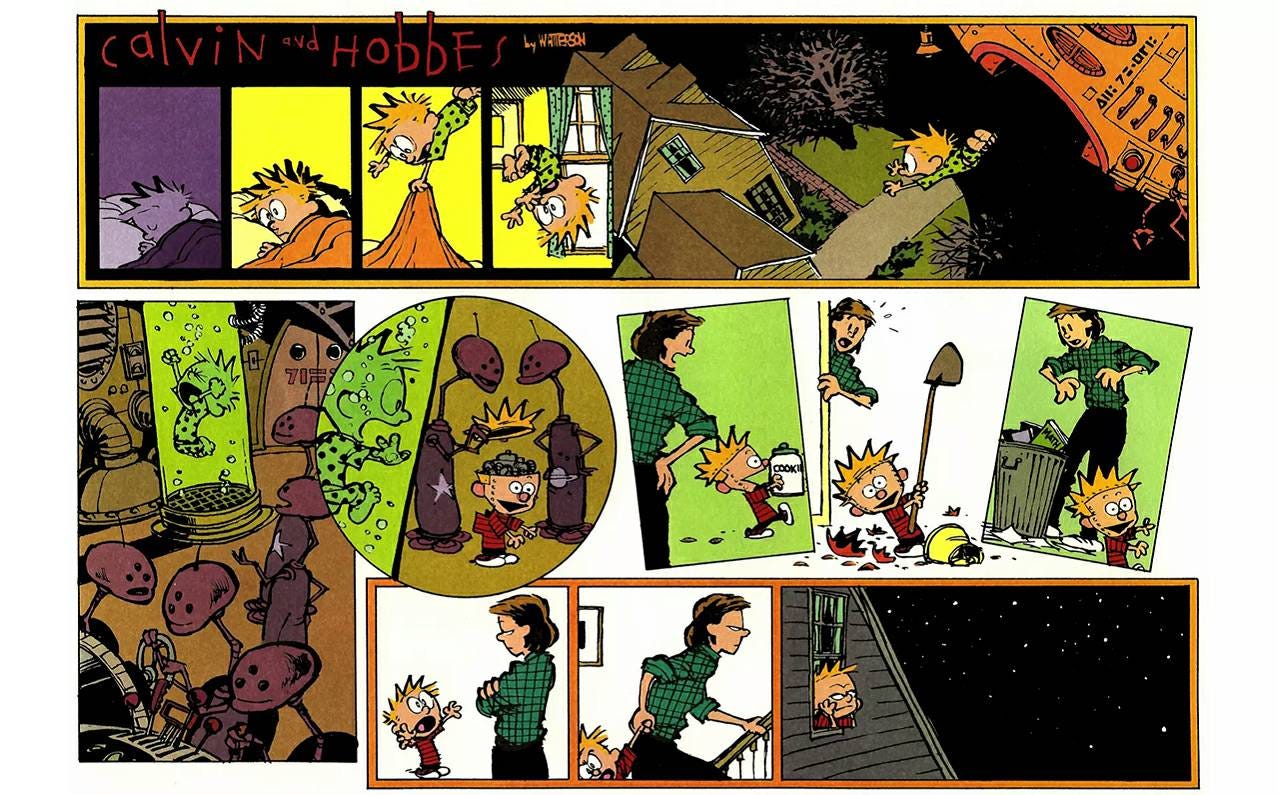

Watterson’s very best Sunday work began a little over a year later, after he negotiated a new agreement with Universal Features dispensing with the restrictive, obligatory three-tier Sunday format seen above. This rigid format mandates, among other things, that the top tier be entirely disposable, giving newspaper layout artists and editors more flexibility in laying out comics on the page. Once free of this restriction and allowed to fill a fixed space with art in any configuration he wished, Watterson designed elaborate Sunday layouts of stunning beauty and power unmatched since the glory days of Krazy Kat and Little Nemo in Slumberland.2

Even so, in this strip Watterson is at the peak of his powers, and he accomplishes something extraordinary, telling a lucid, moving, sentimental story using only images, without a single word balloon or word of text. Silence is important in comic strips, but it’s relatively rare for an entire Sunday strip to forego dialogue completely—and very rare to do so with this level of emotional power. The effect is akin to the best dialogue-free Pixar animated shorts, or even the indelible, wordless four-minute “Married Life” montage sequence from the prologue of Pete Docter’s Up.

Watterson’s cartooning technique in this strip is masterly, from well-chosen hypothetical camera angles and shrewd cropping to slight but significant adjustments in (what I am going to go full pedant and call) mise-en-scène3 to effective use of shot size4 and silhouette.

Let’s break it down.

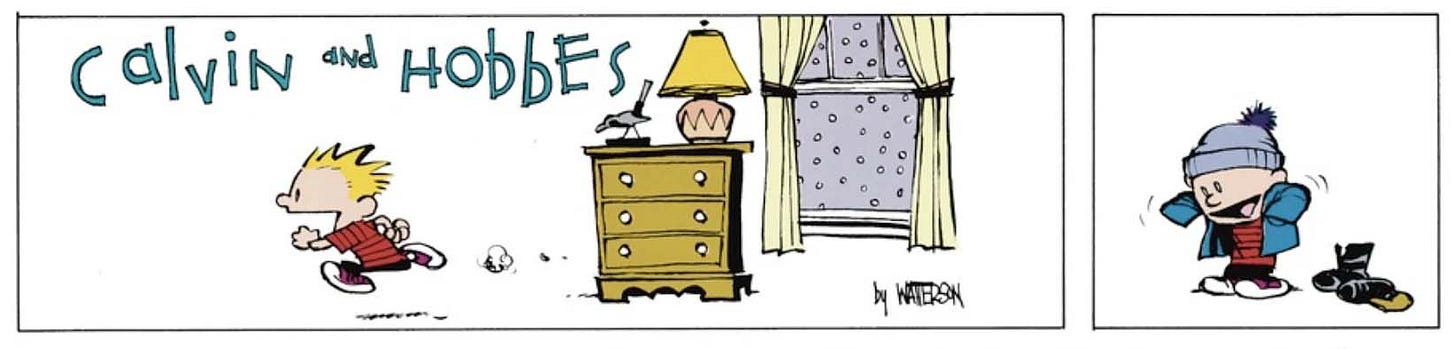

The optional title tier establishes Calvin’s perspective: It’s snowing! It’s the weekend!5 Time to play! The essential story begins on tier 2, with panel 1 establishing Dad hard at work at whatever boring adult thing he’s doing.

Note how the alternating hypothetical camera angles in the first four panels correspond to the points of view of the two characters: In panels 1 and 3, the hypothetical camera is well above table level, representing Dad’s perspective; in panels 2 and 4 the camera is just below table level, representing Calvin’s perspective. While these aren’t literal point-of-view shots, we do see the world from the approximate eye level of the point-of-view character: Dad, Calvin, Dad, Calvin. When Calvin arrives, full of excitement and an invitation to play in the snow, we move from Dad’s perspective to Calvin’s.6 Then comes an even more emphatic version of Dad’s perspective: Look at all this work! As Calvin leaves, disappointed if not surprised, the camera returns to his eye level: Dad is the one talking, but we see the situation from Calvin’s point of view.

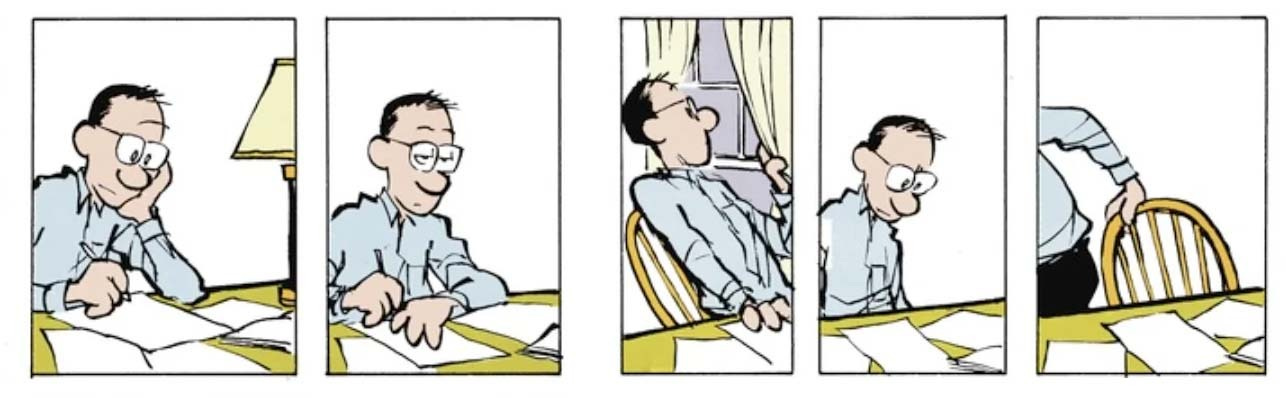

The opening “exchange” of the first four panels is followed by five panels (panels 5 through 9) from Dad’s point of view. Here the camera is static, conveying the tedium of Dad’s planned afternoon—though adjustments in mise-en-scène subtly convey shifts in Dad’s mental state.

In panel 5, as Dad returns to work, the desk lamp from panel 1 returns, evoking his focus and mental energy. Then in panel 6 Dad straightens a bit, a bemused expression (What did I just do?) on his face—and the lamp vanishes, reflecting the break in his mental process. In panel 7 he leans back to look out of the window that obligingly appears, representing his new awareness of other possibilities.7 One last, hard look at the remorseless paperwork (panel 8), and then comes panel 9: brilliantly, dynamically cropped to emphasize just how mentally checked out of boring adult responsibility Dad is—for the moment, that is.

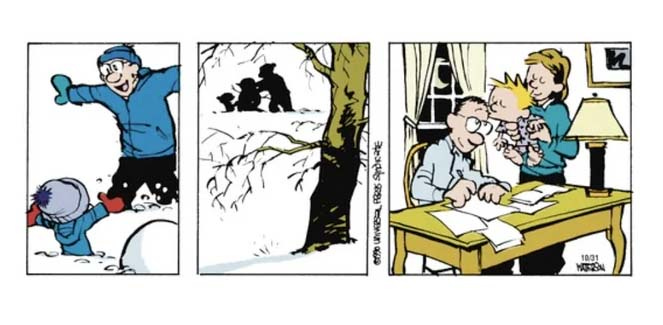

Panel 10, the climax, gives us Calvin’s point of view (directionally, at least; camera elevation is ambiguous), but by showing us Dad’s expression, it cements his status as the protagonist of this strip. Then, in panel 11, the technical coup de grace: a long shot in silhouette as Calvin and Dad work on the snowman.8 The distance from the subjects and the silhouette rendering in this panel make the image, not a snapshot of a particular moment of Dad and Calvin building a snowman, but an iconic representation of the entire act of a father and son building a snowman: a memorable afternoon of play in a single panel.9

The denouement in the final panel packs an emotional wallop—but, significantly, this moment also finds Dad quietly paying the price for his afternoon of family play, still at his boring adult work up to and past Calvin’s bedtime.10 Today Dad is a hero in Calvin’s eyes because of panels 10 and 11. Yet the heroic choice of panel 9 embraces the sacrifice of the last panel: a sacrifice that Calvin doesn’t notice or understand, though Mom surely does.11 This subtlety alone places this strip among Watterson’s finest work.

Read more comics writing >

Available as a print with optional framing and matting.

Here’s an example of a wordless Sunday strip from October 1992 showing off what the fantastical, imaginative side of Watterson’s storytelling could look like when he didn’t have to worry about mandatory panel breaks. For a non-fantastical example, see note 8 below. I’ll have more to say about this in future columns.

Mise-en-scène is a highfalutin critical theater and cinema word that basically means the elements on stage, onscreen, or, in this case, within the panel borders—i.e., whatever the viewer can see at any given moment.

Shot size refers to the distance of the hypothetical camera from the subjects, from closeup to long shot.

It’s the weekend because Dad is at home and not at the office (Calvin’s dad, like Watterson’s own father, is a patent attorney). Calvin’s joy at the snow is for its own sake; this is not a snow day for him—though, if it’s a Sunday (there is a very weak but real tendency for the days of the week in comic-strip time to correlate with the days of publication), and if the snow is formidable enough, he might get one tomorrow.

Notice how in panel 2 Calvin’s mittened finger ever so slightly protrudes beyond the panel border, suggesting a world beyond Dad’s boring adult responsibilities. (As seen in note 2 above and note 8 below, Watterson would do much, much more of this sort of thing in his Sunday work from 1992 on.)

Note how naturally Watterson provides the window when it’s needed, but omits it in the other panels when it isn’t. No need for Dad to change locations in a labored attempt to “explain” the window; we simply accept that it’s there when we see it and don’t question its absence when we don’t. This technique is best understood as a form of image depth control, comparable to shallow vs. deep focus in cinematography. Simplification in cartooning means minimizing or eliminating superfluous elements, especially unnecessary background elements that would clutter up the visuals. Thus, the cartoon image is as “deep” as it needs to be; blank backdrops may not be “realistic,” but they don’t bother us, even when background elements appear or disappear as needed.

This might be the only Calvin & Hobbes strip in which Calvin builds a snowman that we never see! And, of course, we don’t need to; the snowman isn’t the point. When Calvin builds snowmen by himself, his imagination runs in hilarious dark directions; building with his dad, it’s just a snowman.

The unmoving tree in the foreground likewise helps to anchor the moment in an enduring setting, allowing one panel to represent a significant part of a day.

I suspect that, had Watterson not still been locked into the variable-layout Sunday format, he would have done panel 11 as a frameless or borderless panel, allowing the branches of the tree to bleed behind the adjacent panels. This would have enhanced the sense of a scene outside the schema of the briefer moments in time represented by the sequence of bordered panels.

For example, compare the sophisticated approach to panel borders in this nearly dialogue-free Sunday strip from near the end of Watterson’s 1995 run: The first tier of five panels represent typical moments from Calvin’s day; then comes a transition tier of two panels (with extra thick borders) partially inset into the panels above and the drawing below; and the final, borderless panel is an iconic representation of an unbounded moment of time with two friends simply sitting on the rock in the woods. (It would be even more iconic and unbounded without the word balloon, but in this case Watterson evidently felt that some commentary was necessary to tie it all together.)

In this last panel, notably, the mise-en-scène is at its most complete: The window is back to show us the moon in the night sky, while the desk lamp emphasizes Dad burning the late-night oil. We also see part of a framed picture on the wall, perhaps highlighting the domesticity of this good-night kiss moment.

It’s that combination of heartwarming feels and hard reality that invites the comparison to Pixar, which, for a long time, was characterized by the slogan “For every laugh, a tear.”

In the last panel I think that subtle, half-smile on Dad's face is a large part of the heart-warming feel of this strip.

Nicely done. This particular one has always been one of my favorites.

Also of note: a possible subtle nod to the WB Road Runner cartoons. That appears to be a small statue of a road runner on the table in the first frame, and the puff of “smoke” Calvin leaves behind is a gimmick often used when characters dash off in those great WB toons.