Silence speaks: A Cartoon Critic essay

[lessions in what is not said from Jimmy Craig’s “They Can Talk” animal strips]

Most of us understand, at least in theory, that timing is vital to humor. Some people know how to tell a joke; others don’t. For a stand-up comic, a fraction of a second one way or the other can be the difference between a joke landing and bombing, between laughter and silence. For comedy in movies or TV, holding the shot just the right length of time and cutting at the right moment is vital. Animation, where every single frame is deliberately created, is perhaps the ultimate example; the best Looney Tunes cartoons are master classes in comic timing from filmmakers who honed their craft to perfection and learned exactly how many frames to hold the audience in suspense before dropping the other shoe—or anvil, as the case might be.1

Compared to animators, cartoonists (and, for that matter, prose writers) have very little real control over time. Text and comic strips are static forms; the last word, the last panel, is on the page or the screen before the viewer looks at the first word or panel. In principle, a reader or viewer can read the end before the beginning—and sometimes they do!

Yet language, whether written or visual, brings with it conventions that can be used to shape the audience’s experience of time in significant ways. Time in cartooning is highly elastic: A single panel often represents a moment in time, but it can also represent minutes or hours. The gutter (the space between panels) is even more elastic: one panel usually follows closely on another, but days, years, even centuries or millennia can be elided between panels—or no time at all, with simultaneous action in adjacent panels.2

In a cartoonist’s toolbox, one of the notable elements of timing is silence, typically represented by a panel without word balloons or sound effects. The absence of words focuses the reader’s attention on the image and perhaps prompts the reader to process what has been said in the previous panel, or to think about the effect of what has been said on the silent characters—or the non-effect. A silent panel can heighten a reaction shot (or non-reaction).3

The presence or absence of a wordless panel can make or break a joke. The most common position for a silent panel is the penultimate position: the beat or pregnant pause before the punchline. The final panel can also be wordless, allowing the visual to carry the gag: a reaction shot, perhaps.

Here are some examples of effective silent panel use from They Can Talk, a well-done strip by Jimmy Craig about talking animals, mostly pets, often in a vein of humor I’ve called “anthropomorphic observational comedy.” I’ve offered some brief notes on the use of silence in each strip.4

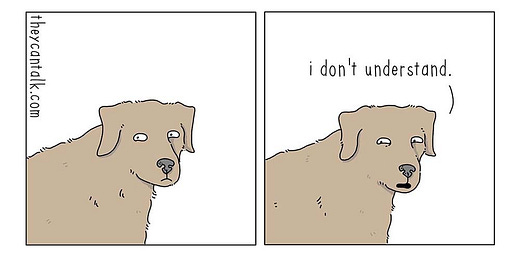

This first strip features typical use of a silent panel in the classic penultimate position. Imagine this strip without the silent panel. The joke still works—it’s not that it’s not funny at all—but it’s not nearly as funny. Why not?

The pause makes the punchline funnier because we feel Mocha’s confusion more acutely. He’s not just puzzled by Ginger’s remark: He’s baffled enough to stop and think about it … and, nope, it still makes no sense!5

In this next strip, silence is part of the punchline:

The silence spotlights the minimalist reaction shot from Shadow,6 who can’t quite believe that Misty is as clueless as she seems. Like, IS SHE EVEN A CAT.

This next strip combines the techniques of the previous two:

The silent penultimate panel, as the last line of dialogue sinks in, gives the silent final panel (wait, I’m in charge?) a poignance it wouldn’t have otherwise. (As with the first cartoon with Mocha and Ginger, you could drop panel 3 and the gag would still be intelligible, but the impact would be greatly diminished.)

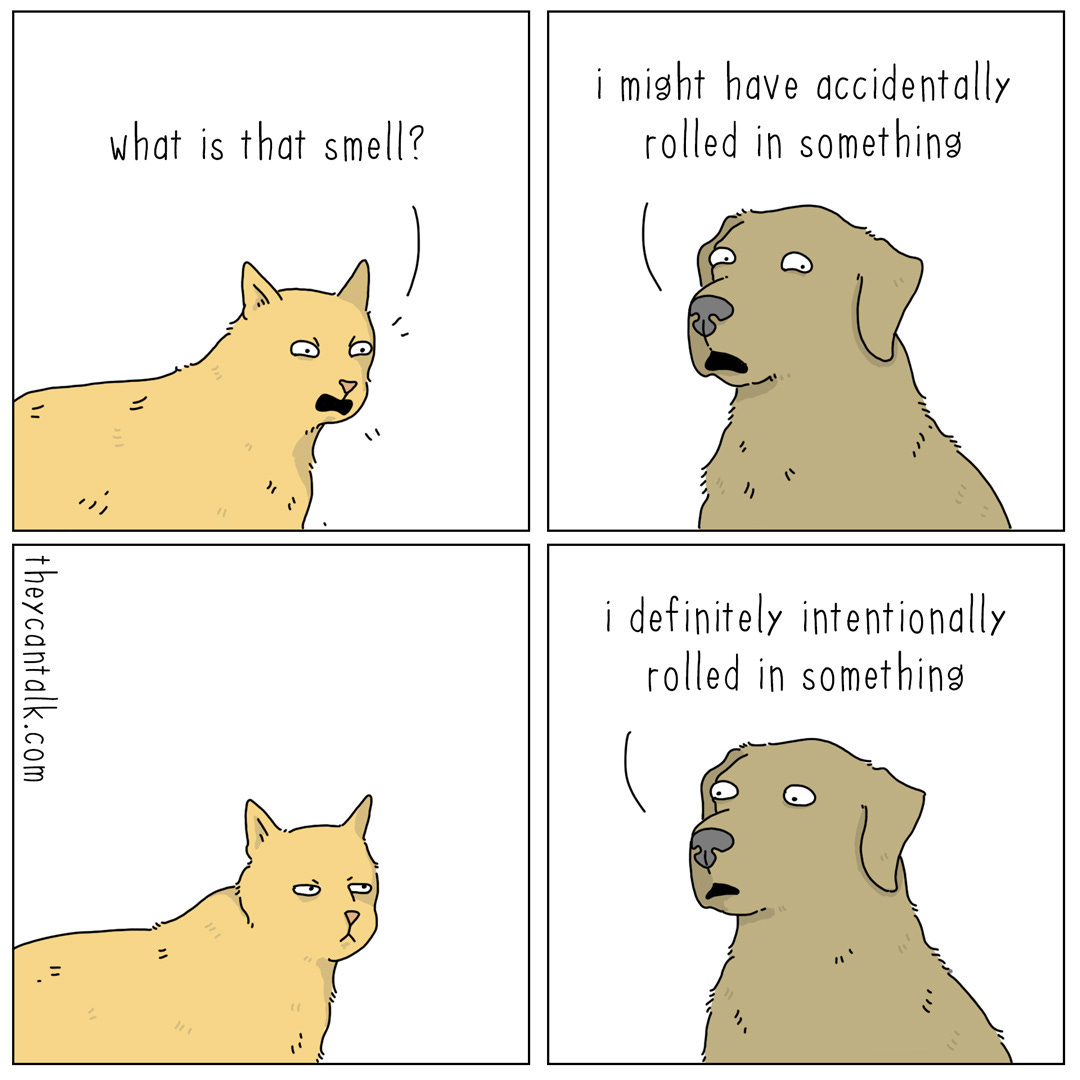

Here’s another typical penultimate silent panel:

Here the silence heightens Ginger’s withering reaction shot to Mocha’s fib, prompting Mocha’s chagrined confession. Imagine this as a two-panel strip without the vertical gutter separating each tier into two panels. Without the pause, Mocha’s confession would come too quickly!

Next, here’s a strip ending, like the one with the geese, with two silent panels—but with a very different effect from that strip, or from any of the others!

The “are you serious” reaction shot in panel 3 is narratively exactly like the penultimate panel in the last strip with Ginger and Mocha. Yet panel 4 is different from any other silent panel on this page: It’s not just that our would-be eagle is unfazed by the future bullfrog’s glare; rather, it’s so unaware of it that the usual sense of sequence is obliterated. In other words, in this strip panels 3 and 4 are effectively simultaneous.

As with the previous strip, you could remove the vertical gutter and make each tier a single panel. Putting the dialogue in the first two panels into a single panel would change nothing: We would still understand that the tadpole on the left was speaking first, followed by the tadpole on the right. A single panel can accommodate this kind of chronological sequence; two panels aren’t necessary. Yet where, in the previous strip with Ginger and Mocha, the final combined panel would carry a similar sense of left-to-right process (because Ginger is reacting to Mocha), in the tadpoles’ story the final combined panel would simply be a moment in time, with no indication of duration.7

This is a good example of how gutter space (like panel space!) is temporally elastic! In every other strip on this page, the space between panels 3 and 4 represents a beat in real time—but not in the story of these tadpoles.

In this next strip, silence is used in panels 2 and 3 as a narrative element, emphasizing the action.

On another note, the compositional choice to frame the world of this strip with the panels (almost) entirely filled with earth—so that we don’t see the open air above, and, crucially, the implied bird—places us squarely in the worms’ world.8

In this next strip, the use of silence in the last two panels subverts the withering reaction shot convention seen in previous penultimate panels:

Unexpectedly, the silent last panel shifts the impact of the previous one into a punchline like the one with the geese: one beat to think about what was said, and another beat as it really sinks in.

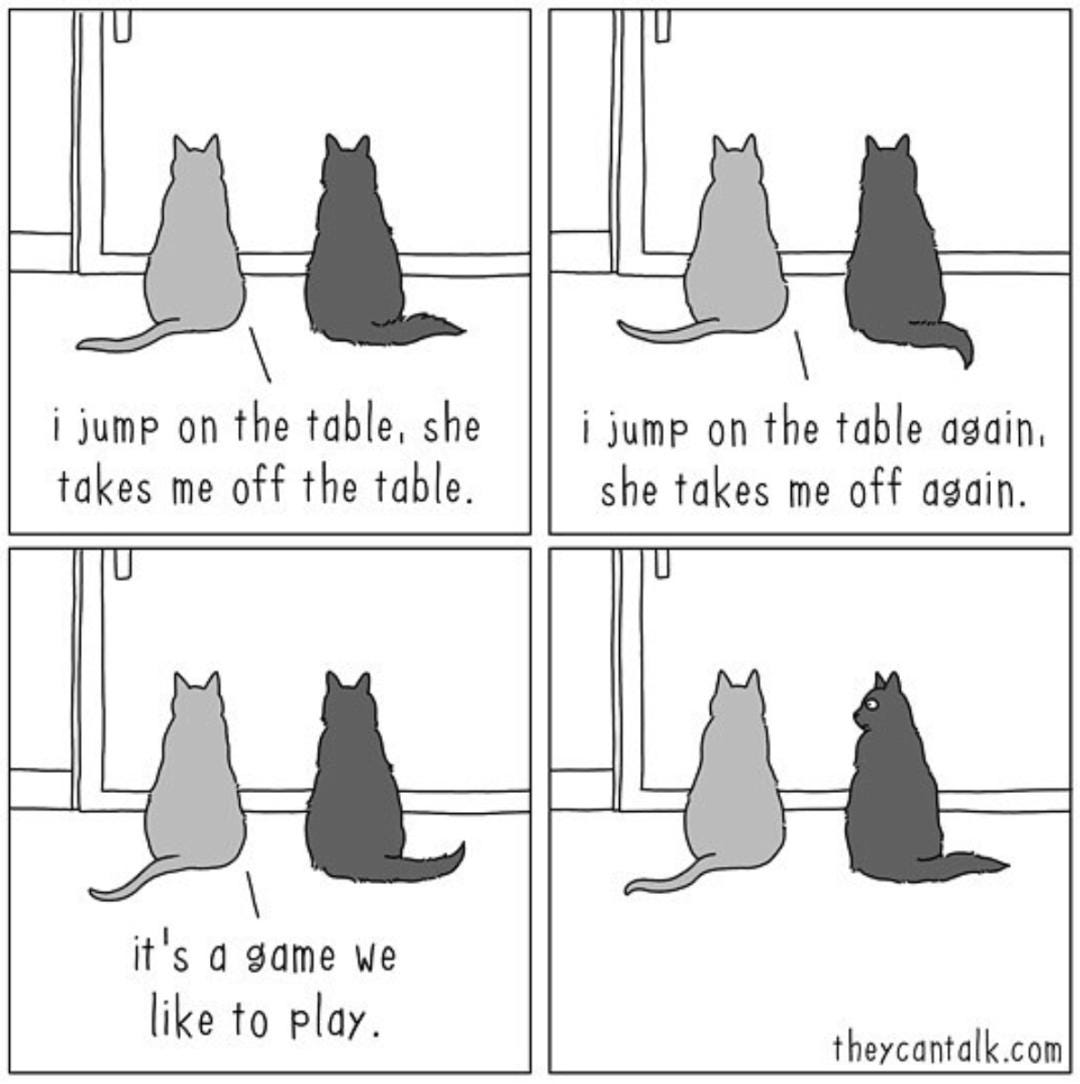

In the strip below, alternating text and silence makes panels 2 and 4 a kind of visual commentary on the verbal content of panels 1 and 3:

Not everything that sounds like a complaint is an invitation for someone to solve the apparent problem!9

Finally, here’s another typical silent penultimate panel, much like in the first strip with Mocha and Ginger—except this time, instead of incomprehension, the moment of silence emphasizes a deeper insight.10

Without the penultimate panel, there’s no sense that the identity-conscious mountain goat has been unexpectedly moved by an aesthetic appeal to consider another point of view. There’s no arguing with beauty. Silence speaks!

Read more comics writing >

For detailed analysis, see Jaime Weinman’s Anvils, Mallets & Dynamite: The Unauthorized Biography of Looney Tunes.

To understand this better (along with a great many other things!), see Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics.

This assumes, of course, that we’re talking about a multi-panel strip like the ones examined here, as opposed to the one-panel strips which this series has focused on until now!

For the sake of convenience, I’ve given some of the pets ad-hoc names (apologies to Mr. Craig if they already have names unknown to me!).

So minimalist! Nothing but a turned head and an eyeball, but we know exactly how Shadow feels.

The fact that the gutter doesn’t matter narratively or temporally doesn’t mean it has no effect! Despite the simultaneity of the panels, giving the future eagle the final panel all to itself emphasizes its serene occupation of its own reality, untouched by the opinions of silent saysayers. Thus, the four-panel solution is the correct one here.

No reaction shots here, because none of the worms can see anything relevant!

I find the use of scale (or degree of closeness, i.e., shot size) here interesting. Moving from the lonely anglerfish in panel 1 to panel 2, the camera moves back to accommodate the approaching arowana. Panel 3 is the most “cluttered” panel—the only panel to show both fish and have dialogue—so you might expect Craig to keep the camera back. Yet instead he zooms in (so much that both fishes’ tails are cropped) to emphasize the volume of the angler’s angry shout. Panel 4, by contrast, is the only panel with only one fish and no other elements, and you might expect him to stay zoomed in to fill up the space, yet he pulls back even more than in panel 1, emphasizing the (happy!) loneliness. (Note how in this final panel our anglerfish is swimming just a little higher above the ocean floor in panel 4 than in panels 1 and 2! It could be argued that Craig is simply filling the space, but I think it also corresponds to the angler’s elevated mood.)

No idea why this one strip uses curly single quotes around ‘valley goats’ where everywhere else Mr. Craig resolutely uses tall straight quotes and apostrophes (and double quotes in the strip with the fish)! Curly quotes look nicer. (No arguing with beauty.)

This was a fun post. And thank you for introducing me to a new comic!

It’s so nice to see that the School of Visual Arts was a great investment!