Sushi and transcendence Q&A!

[a theologically suggestive introduction to my favorite food, with more to come]

I have an atheist friend who says that when he eats really good sushi, it makes him want to believe in God. I think we have similarly transcendent experiences of sushi, although as a believer I naturally express it a little differently: I say that when I eat really good sushi, I know that God loves me.

Q. You’re kidding, though, right? Or exaggerating?

A. I’m honestly not, any more than Peter Kreeft was kidding or exaggerating when he wrote, “There is the music of Johann Sebastian Bach; therefore there must be a God.” I recognize, of course, that such propositions may lack demonstrative force for the unconvinced: and, in the case of sushi in particular, the force of the premise may be very varyingly experienced! But I value my friend’s conflicted, semi-theological experience of sushi all the more for his lack of religious faith. (For anyone who is really interested in exploring how sushi—or any other food experienced as transcendent or sublime—relates to God, I do have more to say, but not here.)

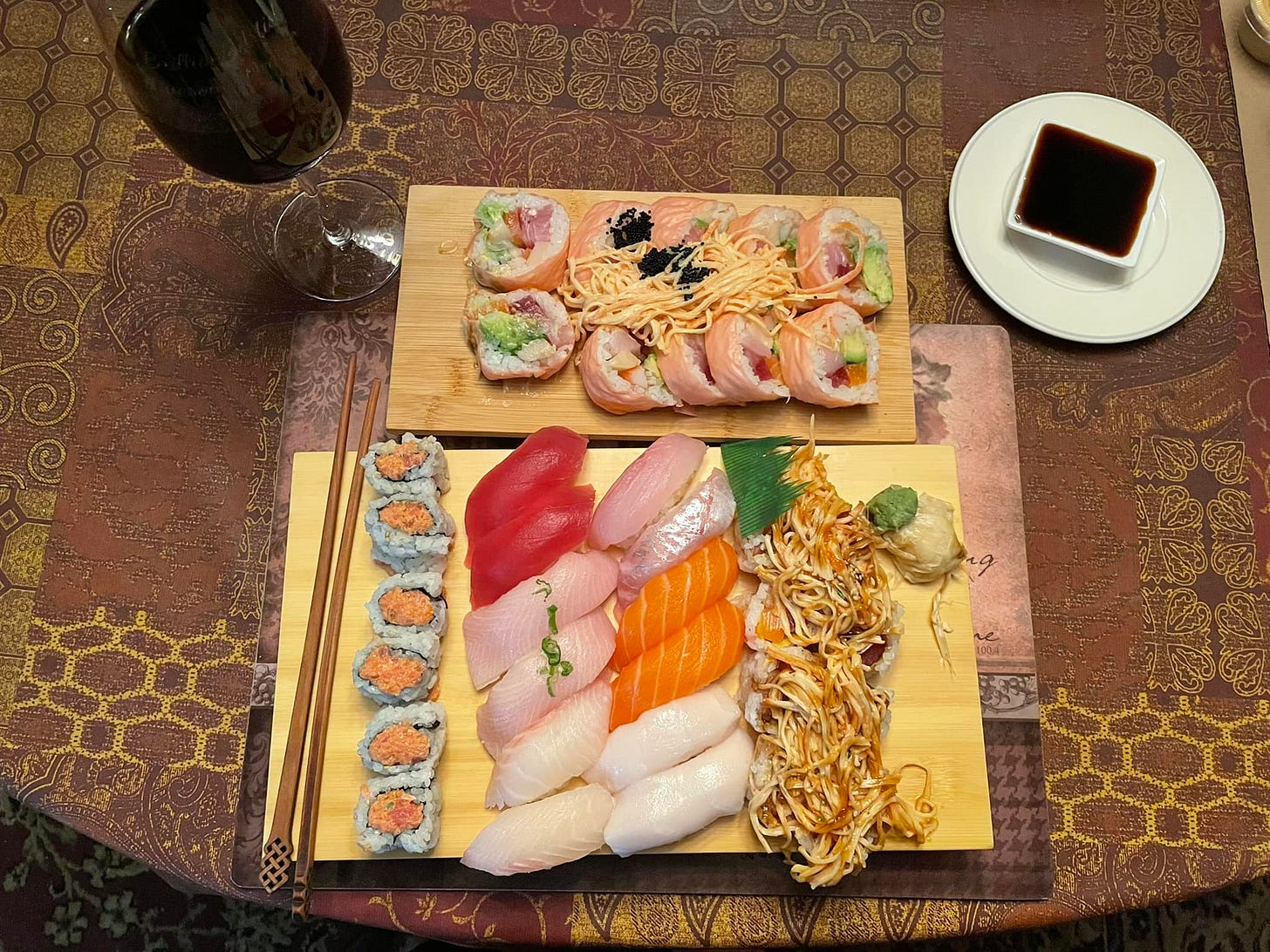

Not all sushi is transcendent! Supermarket type sushi is fine, but nothing special. About once a month I treat myself to what I call “The Good Sushi” at a local place, but it isn’t transcendent. Another place in town serves what I call “The Excellent Sushi.” I am lucky enough to live in a town where I can get even “The Transcendent Sushi”—on rare occasions, of course, because it’s expensive! On truly exceptional occasions (once every few years) I make a pilgrimage for the most sublime sushi I’ve ever had.

Q. I don’t get it! Raw fish? What’s the appeal?

A. So let’s begin by defining terms.1

Sushi isn’t necessarily raw fish (cooked fish is also used), or even fish at all (vegetarian sushi is a thing, as is sushi involving other types of meat2). Nor is raw fish, even when properly prepared and served as a meal, necessarily sushi; a slice of raw fish by itself is sashimi, not sushi. (Good sashimi is amazing, but for me at least it doesn’t quite cross into the rarefied precincts of the transcendent.)

The term “sushi” refers not to fish, but to the vinegared rice. A wide variety of ingredients, properly prepared with salted, vingared rice, can constitute sushi. The invention of sushi goes back to a time when fermented or vinegared rice and salt were used to preserve fish. At first, when the fish was eaten, the rice was thrown away—until Japanese people discovered that salted vinegared rice and fish go really well together!

Q. Why is that, though? Fish is good and rice is good, but what’s so special about putting them together?

A. First of all, it has to be the right fish and the right rice, properly prepared.3 When everything comes together just right, you get a superlative combination of textures as well as tastes (potentially all five basic tastes—sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami or savoriness) unlike any other dish on the planet. (Again, sushi doesn’t have to be made with raw fish, but when I talk about transcendent sushi, raw fish is definitely involved!)

Why? Let’s start with the fish. The texture of fish is unlike the texture of any land animal. Even the tenderest pork chop or cut of steak is tougher than fish, because land animals spend their lives using their muscles to resist the pull of gravity. Not having to support their body weight in the same way, fish muscle fibers are shorter and softer than those of land animals. The connective tissue holding the muscle fibers together is delicate and weak. (As with land animals, the belly of the fish is the tenderest and best part, while the muscles that work more, like the tail muscles, are tougher. Good sushi chefs select the best cuts of fish for the dish they want to make.)

Q. Why is fish so special raw, though? After all, cooking beef and pork (up to a point!) makes them softer and more tender—you couldn’t eat them otherwise!

A. True! Yet even with beef, the rarer end of the spectrum is better than the more well-done end. Cooked fish is flaky and light—but raw fish has an utterly unique texture, soft and fleshy and delicate.4

At least, it’s soft and delicate when it’s been properly prepared from capture to serving! “Sushi grade” is a meaningless marketing term, not a real standard, but the best sushi is made from high-quality fish that has been killed quickly after capture, typically bled and gutted quickly, iced thoroughly, and correctly aged (like aging beef) for up to a week or even longer, depending on the type of fish—a process crucial to the umami flavor.

Killing the fish quickly after capture, besides being considered the most humane approach, prevents stress and flopping around, with accompanying depletion of the energy-producing molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and buildup of lactic acid. Fish served in the US is often flash-frozen for at least a week (killing any parasites, which are rare in any case).

After thawing, the aging or maturing process allows enzymes in the muscles to break down various organic compounds (like ATP) into delicious amino acids, proteins, and other compounds (like glutamate and inosine monophosphate or IMP, both associated with the umami taste). Aging also softens the fish, breaking down connective tissues and loosening muscles, making it easier to remove bones and of course enhancing that incredibly delicate texture that makes for the best sushi. Without proper aging, fish can be tasteless, chewy, or otherwise nonideal (as cheap sushi is usually nonideal).

Q. What if I just can’t deal with raw fish?

I understand! It was an acquired taste for me. Going on 30 years ago, I was part of a production team at a major publisher, and a vendor would sometimes take the team out for lunch, often sushi. The first couple of times I found the raw stuff difficult … but by the third time or so, I noticed something starting to click. It wasn’t long before I realized I loved sushi, and not longer after that it became by far my favorite food.

Q. Okay, now what about the rice?

A. The rice is really important! A good bite of sushi fills the mouth, soft fish pressing against firm rice, the salty sourness of the rice balanced by the savor of the fish and perhaps a bit of sweetness from sugar often used in the rice recipe as well. It’s that marvelous balance of textures and tastes, no one element predominating, that makes really good sushi the transcendent experience that it is.

Of course it has to be the right kind of rice: white, ideally short-grained, sticky but not gummy, with just the right amount of firmness to offset the softness of the fish, prepared with the chef’s preferred ratio of vinegar, salt, sugar, and other ingredients.

Although sushi can be served as a dish of ingredients scattered over rice (chirashizushi), it’s often prepared in discrete units offering an ideal balance of fish and rice, like the classic nigiri (a slice of fish over a finger-like5 rice clump), or like sliced rolls often wrapped in seaweed, that are meant to be eaten in one bite.

A bit of soy sauce, and perhaps a dash of wasabi,6 can enhance the experience, but you don’t want to overwhelm the delicate equilibrium of tastes! Some aficionados say that only the fish should touch the soy sauce, since the rice would soak up too much of it. I admit I like a certain penetration of soy sauce into the rice, though I certainly don’t want it to be sopping.

Q. Okay, okay! So where do I find “The Transcendent Sushi”?

A. That depends, obviously, on where you live! In New Jersey, where I live, the best sushi I’ve ever experienced is in Somerville, Somerset County (central Jersey). The place used to be called Shumi, but it was rebranded Ai Sushi after former owner and master chef Kunihiko “Ike” Aikasa retired and left his former sous chef, Junichi Akaishi, in charge of the menu.

Ai Sushi isn’t easy to find: From the street, it’s a nondescript door in a strip mall or something, alongside a Mexican restaurant—and behind the door is a nondescript hallway that you feel sure has to be the wrong place. At the end of the hallway, though, is an elegant establishment, and I have no words for how transporting the omakase7 is.

Here in northern NJ, the best place I’ve ever found happens to be pretty close to my home. It’s Wabi Sabi in Bloomfield, Essex County. At Wabi Sabi I usually order my favorite things à la carte, with helpful suggestions from one of the servers who knows my tastes.

Q. And what exactly does God have to do with this again?

I started to try to address the “sushi and God” question here—but, unsurprisingly, my thoughts wound up getting out of hand! I saved that discussion for a follow-up “God thoughts” essay … see below!

Read more entries labeled Curious >

God and sushi: More theo-nerdery

Back in March I wrote what I called a “theologically suggestive” introduction to my favorite food, in which I tried to explain, to the best of my ability, what makes excellent sushi so transporting. In this sprawling, theo-nerdy follow-up, I will try to explore philosophically…

At some point I’m going to have to write a Boilerplate Non-expert Disclaimer acknowledging that I am not—well, in this non-boilerplate case, a sushi chef or even a sushi food critic, and what little I know about sushi I present here with great openness to additions and corrections from those who know more and better than I.

For general purposes, and in ordinary culinary terms, fish is a kind of meat. As a Catholic writer writing in Lent, I should acknowledge in passing that, in Latin Friday abstinence usage, fish is not considered “meat,” and is famously exempt from the Lenten Friday no-meat rule. (I sometimes tell my students, “To oversimply, ‘no meat’ means ‘nothing warm-blooded’.” The discipline of the Eastern Churches, both Catholic and otherwise, is far more rigorous on this point. Yes, I am aware that exceptions have been made for, e.g., beaver and capybara because of their amphibious lifestyles; hence “to oversimplify”! If those animals were realistic menu options where we live, I would mention it to my students.)

Ideally, of course, fasting and abstinence should be in spirit, not just in letter, and for me personally it would be absurd to eat sushi on a Lenten Friday, or for that matter during Lent at all! Honestly, I shouldn’t even be writing about sushi in Lent, but I have reasons for wanting to do this piece now. Anyway, I’m publishing this on a Sunday, so there’s that.)

A popular documentary, Jiro Dreams of Sushi, explores at lengths the issues of fish quality and rice quality as well as proper preparation.

Some kinds of fish, like eel, are never eaten raw. Freshwater eel, or unagi, is always cooked, because its blood contains a neurotoxin dangerous to humans unless it’s cooked. Eel and other cooked fish can be easier for sushi beginners than raw fish, although note that eels are on the sustainable seafood advisory list because their populations are under pressure due to overfishing.

The Japanese word nigiri literally means “two fingers,” but is used to mean “gripping” or “grasping”—apparently a reference to the rice molding technique rather than the resulting finger-like rice shape.

In the US, “wasabi” is almost never actually wasabi. It’s usually horseradish, a similar mustard-family plant that is easier to grow and prepare.

Chef’s choice (literally “I leave it to you”)—absolutely the way to go at Ai Sushi.

I settle for the grocery store stuff but then boost it with Tamari soy sauce and freeze-dried actual wasabi powder, which is milder than the fake stuff and has more of a "veggie" taste. Probably still nothing like fresh grated wasabi though...

Have you ever had outstanding ceviche? Your sister and I had it once in a restaurant in North Jersey, and it was so marvelous, we wanted to cancel our entree order and just get more ceviche. And they had given us a generous portion. Never found its equal, even with 11 trips to Mexico. Sadly, that restaurant closed. You make me almost want to try it again, although if there was eel in it, I couldn’t eat it unless I didn’t know. I’m glad you have so many things (and people, of course) that make you happy!