Reflections on voting as a pro-life Catholic

Preamble to an anti-Trump polemic (yes, this is a preamble)

Read next: A referendum on elections: Why defeating Trump is the best move for the US and the GOP

One of my earliest political memories is from the morning after Election Day in 1980. At the Catholic school I attended, I asked a teacher, a member of the Christian Brothers, who he had voted for. “The guy who didn’t win,” he replied, meaning Jimmy Carter. My father, a Reformed minister who had voted for Democrats from Kennedy in 1960 to (I believe) McGovern in 1972, voted for Ronald Reagan in 1980. He would never vote for another Democrat again. He died in 2021 a few months after voting for Donald Trump in 2020.

The divergence in 1980 between my father and that Christian Brother was a case in point of so-called ideological sorting unfolding during the second half of the twentieth century. Prior to the sorting, it was ideologically feasible for socially conscious Christians, Democratic leaders, and other left-leaning parties who had joined in supporting civil rights and opposing the Vietnam War to extend their defense of the vulnerable to opposing abortion and euthanasia along with the death penalty. Democrats such as Ted Kennedy, Jesse Jackson, and Al Gore espoused pro-life views, and such stoutly leftwing figures as the antiwar and antinuclear activist priest Daniel Berrigan, SJ and the self-described “Jewish atheist” writer Nat Hentoff would continue to do so throughout their lives. (A pro-life “Catholic atheist” of great significance in my life: Roger Ebert.) Among those more supportive of relaxing abortion restrictions, on the other hand, were the Southern Baptist Convention and a number of conservative Republicans.

In the end opposition to abortion came to be regarded as a rightwing stance aligned with the Republican Party, while abortion rights were enshrined as a key principle of the Democratic Party. Pro-choice Republicans and pro-life Democrats still exist, but the latter, at least, have become an increasingly endangered species with no voice in their party.

I didn’t, of course, know any of this in the 1980s. All I knew, the first time I voted in 1988, was that as a Christian (not yet a Catholic) I was pro-life, and the Democrats weren’t. I voted for George H. W. Bush—and I continued to vote for Republicans for most of my adult life.

A “broad spectrum” and a “pre-eminent priority”

Was I a one-issue voter? Yes and no.

In 1992 I began graduate religious studies at St. Charles Borromeo Seminary in the Philadelphia area. It was a huge deal in that world when Pope John Paul II promulgated his landmark 1995 encyclical Evangelium Vitae (The Gospel of Life). In this document the pope laid out a sweeping vision of what it means to be “unconditionally” or “unreservedly pro-life,” calling for the building of a “culture of life” in opposition to what he condemned as “the culture of death.” Drawing on the Second Vatican Council’s Pastoral Constitution On the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes), he set forth a taxonomy of “crimes and attacks against human life”:

“whatever is opposed to life itself”: murder, genocide, abortion, euthanasia, suicide

“whatever violates the integrity of the human person”: mutilation, torture, coercion

“whatever insults human dignity”: dehumanizing living or working conditions; arbitrary imprisonment; deportation; slavery, human trafficking, and prostitution

To this list of pro-life concerns John Paul II added “the ancient scourges of poverty, hunger, endemic diseases, violence and war,” and made a strong case for sharply limiting or abolishing the death penalty (revising the recently released Catechism of the Catholic Church to reflect this new critical scrutiny).

That wasn’t all. The pope called out “an unjust distribution of resources between peoples and between social classes” as a form of violence against “millions of human beings, especially children, who are forced into poverty, malnutrition and hunger,” insisting that “Communities and States must guarantee all the support, including economic support, which families need in order to meet their problems in a truly human way.” He also warned about “the spreading of death caused by reckless tampering with the world’s ecological balance, by the criminal spread of drugs, [and] by the promotion of certain kinds of sexual activity which, besides being morally unacceptable, also involve grave risks to life.”

This encyclical helped to fix in my mind, with increasing clarity over time, the framework of what has come to be called a consistent life ethic: a blend of “conservative” and “liberal” concerns including social and economic justice, care for the environment, skepticism about war, and opposition to torture and the death penalty as well as abortion and euthanasia. Other concerns particularly applicable to the American experience—highlighted every four years by the Catholic bishops of the United States in their voter guide, Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship—include gun violence and racism; excessive police force is another. “Pro‑life for the whole life” and “consistent non-violence from the womb to the tomb” are slogans used by pro-lifers whose work I have admired, like Destiny Herndon-De La Rosa of New Wave Feminists and Aimee Murphy of Rehumanize International.

At the same time, there is a hierarchy to that list of “crimes and attacks against human life”—and, among the most serious, those “opposed to life itself” (murder, genocide, abortion, euthanasia, suicide), two stand out as politically divisive. Reflecting this, the US bishops, in their 1998 statement Living the Gospel of Life: A Challenge to American Catholics, wrote:

Respect for the dignity of the human person demands a commitment to human rights across a broad spectrum … Yet abortion and euthanasia have become preeminent threats to human dignity because they directly attack life itself, the most fundamental human good and the condition for all others. They are committed against those who are weakest and most defenseless, those who are genuinely “the poorest of the poor.”

Regarding that “broad spectrum” of issues, the statement continued:

Opposition to abortion and euthanasia does not excuse indifference to those who suffer from poverty, violence and injustice. Any politics of human life must work to resist the violence of war and the scandal of capital punishment. Any politics of human dignity must seriously address issues of racism, poverty, hunger, employment, education, housing, and health care. Therefore, Catholics should eagerly involve themselves as advocates for the weak and marginalized in all these areas.

These basic commitments are reiterated in every edition of Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship. From the latest iteration:

The threat of abortion remains our pre-eminent priority because it directly attacks our most vulnerable and voiceless brothers and sisters and destroys more than a million lives per year in our country alone. Other grave threats to the life and dignity of the human person include euthanasia, gun violence, terrorism, the death penalty, and human trafficking. There is also the redefinition of marriage and gender, threats to religious freedom at home and abroad, lack of justice for the poor, the suffering of migrants and refugees, wars and famines around the world, racism, the need for greater access to healthcare and education, care for our common home, and more.

Effectively, then, the message from Church leaders is that all of these issues, whether “liberal” or “conservative,” are important—but abortion is the most critical, followed by euthanasia.

Different kinds of wiggle room

For many US Catholics, the obvious conclusion has long been that pro-lifers should presumptively vote for Republicans, and at any rate a vote for a pro-choice Democrat can never be justified by appealing to other issues. Not that the pope or the US bishops said that—though other voter guides by and for Catholics have. In any case, for many Catholics across the ideological spectrum there has been little if any sense of conflict around that “broad spectrum” of issues, since in practice most Catholic voters and politicians tend to pick and choose among the Church’s “conservative” and “liberal” concerns based on their own ideological preferences.

That is, Catholic voters and political figures who are more liberal (public examples include Joe Biden and Sonia Sotomayor) tend to align more with Catholic teaching on issues like the death penalty, racism, environmentalism, and the plight of the poor and immigrants and refugees, all while downplaying or rejecting Church teaching regarding abortion and euthanasia. Conversely, more conservative Catholics (e.g., Marco Rubio, Clarence Thomas) are often strongly against abortion and euthanasia, but in favor of the death penalty, against gun regulation, suspicious of policies or programs aimed at helping migrants and refugees as well as the poor, and skeptical that racism and environmental concerns like climate change are real problems (at least on the scale that progressives claim).

More broadly, the views of Americans generally and of the two major political parties have tended to increasingly align into nonoverlapping groups, making the consistent life ethic a marginal view. Whether this amounts to “sorting” or “unsorting” depends, I guess, on your point of view.

In defense of Catholic conservatives, the Church itself distinguishes between its clear and absolute teaching on issues like abortion and euthanasia and its “soft” teachings on social issues like how to address poverty and gun violence, where there’s no one clearly right answer. Even the death penalty was affirmed as valid as recently as 1949 by Pope Pius XII, and resisted in a qualified way by John Paul II before being declared “inadmissible” by Pope Francis. Thus, for example, in a 2004 memorandum Cardinal Ratzinger (who the following year would become Pope Benedict XVI) wrote:

Not all moral issues have the same moral weight as abortion and euthanasia. For example, if a Catholic were to be at odds with the Holy Father on the application of capital punishment or on the decision to wage war, he would not for that reason be considered unworthy to present himself to receive Holy Communion. While the Church exhorts civil authorities to seek peace, not war, and to exercise discretion and mercy in imposing punishment on criminals, it may still be permissible to take up arms to repel an aggressor or to have recourse to capital punishment. There may be a legitimate diversity of opinion even among Catholics about waging war and applying the death penalty, but not however with regard to abortion and euthanasia.

The above passage has been much quoted by conservative Catholics in defense of their death penalty advocacy. On the other hand, in the same document Ratzinger refuted the absolutist stance of many conservative Catholics regarding the impossibility of voting for a pro-choice candidate under any circumstances:

A Catholic would be guilty of formal cooperation in evil … if he were to deliberately vote for a candidate precisely because of the candidate’s permissive stand on abortion and/or euthanasia. When a Catholic does not share a candidate’s stand in favor of abortion and/or euthanasia but votes for that candidate for other reasons, it is considered remote material cooperation, which can be permitted in the presence of proportionate reasons.

This is a solid application of what Catholic moral tradition calls the principle of double effect, which describes when actions that have both good and bad consequences are or aren’t permissible. The catch, of course, is the words “in the presence of proportionate reasons.” From a Catholic perspective, one might easily ask: What could ever be proportionate to “directly attacking our most vulnerable and voiceless brothers and sisters and destroying more than a million lives per year in our country alone”? Short of nuclear war, not much that I could think of. (I must confess that it took me awhile to appreciate the global consequences of the second Bush administration’s foreign policy, particularly in the Middle East and North Korea.)

And that’s about as far as my thinking went for many years.

The least problematic viable candidate

In 2008, I not only voted for John McCain, I published thousands of words at a prominent Catholic blog arguing both against voting for Barack Obama and in defense of voting for McCain. At the time, a few well-known Catholic bloggers were arguing against voting for either major-party candidate on the grounds that both advocated policies contrary to Church teaching on fundamental pro-life issues (McCain supported embryonic stem-cell research). Influenced by these arguments, some Catholics were concluding that the only moral choices in such an election were either to vote for some quixotic third-party candidate or not to vote at all.

This hyper-scrupulous view is clearly contrary to the logic of Ratzinger’s memorandum (not an authoritative document, but his application of Catholic moral theology is bulletproof). Drawing in part on Ratzinger’s analysis, I formulated and defended a general rule against voting scrupulosity: It is always morally acceptable to vote for the viable candidate you consider least problematic. That is, of the candidates you think have a realistic chance of winning (in practice, usually the two major-party candidates), even if they both advocate serious evils, you may always vote for the one you think will do on balance more good and less harm.

I did not argue that it is always morally necessary to vote for the least problematic viable candidate. There can also be credible arguments, I believed, for voting for third-party candidates and potentially even for not voting at all. Exercising the right to vote, in the language of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, is a form of “co-responsibility for the common good” (CCC 2240), but this co-responsibility is highly diffused (no election outcome is decided by any one person’s vote, or by any one person and all the people they know, etc.) and subject to many considerations (e.g., whether one lives in a battleground state or a solidly “red” or “blue” state). “A vote has lots of effects, only one of which is increasing the probability of a particular candidate’s victory,” as Gregory Brown would later write in The Public Discourse.

I wrote a lot in 2008 about the morality of voting, drawing on Catholic moral teaching, practical analysis, and game-theory principles, which I won’t recap here! Suffice to say that I believed then, and believe now, that there is no one right way to vote in every election that all right-thinking Catholics are obliged to embrace; there is room for “legitimate diversity of opinion” on the best way to use the tiny aye or nay of one’s vote to try to serve the common good.

Not all prudential opinions are created equal, of course. Some are far more well-grounded and reasonable than others. We can certainly try to persuade others of the prudential case for our view and against their view. Still, morally absolute statements like “It is always a sin to vote for a candidate with view X” are, strictly speaking, false; it always depends on what the proposed proportionate reasons are.

In 2012 (the year I began diaconal studies at Immaculate Conception Seminary School of Theology), I believe I voted for the first time for a third-party presidential candidate. It was still axiomatic to me that I couldn’t support Obama, but Mitt Romney struck me as too milquetoast, too elite and out of touch, and lacking in depth and conviction. (I must also report that I wasn’t thrilled about his Mormonism. I could not have imagined at the time just how much Romney’s stock, so to speak, would rise in my eyes over the next dozen years, and how glad I would have been to see him the Republican nominee in any subsequent election.)

And then came Trump

It’s hard to recall now how wary and suspicious of Donald Trump’s candidacy many on the religious right were for a long time. This is not the place for an analysis of Trump’s assets and liabilities or how, despite his considerable weaknesses and unattractive qualities, he managed to become first the Republican frontrunner and eventually a quasi-mythic hero to many on the right. Suffice to say I found his growing viability as a candidate horrifying and I never changed my mind. I wanted to see Hillary Clinton defeated—but I wanted any other Republican candidate do it.

I found myself forced to consider a class of questions the likes of which I had never before had to consider. What would it mean for the moral credibility of the pro-life movement to have so debauched, amoral, ignorant, and mean-spirited a man as our effective standard bearer? How would embracing him affect the judgment and perspective of Christians and conservatives? (Note to readers who object to my characterization of the former president, who still consider him patriotic, heroic, and virtuous: I am sorry for being unable in this essay to expand my argument to address your point of view; I can only thank you for illustrating my point for the benefit of other readers.)

With normal politicians, I had been content to use candidates’ stated policy positions as a proxy for the causes that they would favor or oppose. With Trump, this approach seemed inadequate; the question “What will the actual effects be of having this particular man in office?” became more pressing.

Pro-life friends that could never before have imagined voting Democrat began to talk seriously about voting for Clinton. Others supported voting for a third party, such as the American Solidarity Party. No less staunchly conservative and pro-life a Catholic voice than Archbishop Charles Chaput of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia wrote that both candidates had such “astonishing flaws” that “neither is clearly better than the other.” Catholic ethicist Charlie Camosy—who opposed Clinton, calling her abortion views “heinous and dangerous”—nevertheless argued persuasively that reasonable, faithful Catholics could disagree:

Here are just a few possible arguments that a reasonable person could easily believe serve as proportionate reasons [for voting for Clinton]:

Donald Trump is a ridiculously dangerous, child-like egomaniac who cannot be trusted with the presidency, and voting Hillary Clinton is the best way to stop him.

Donald Trump is a fake pro-lifer who cannot be trusted to appoint pro-life justices or to make protecting prenatal children a priority.

The Republican party is a fake pro-life party which, at least at the federal level, has proven over decades that it cannot be trusted to appoint pro-life justices or to make protecting prenatal children a priority.

The Republican strategy of banning abortion won’t stop people from getting abortions any more than prohibition’s strategy of banning alcohol stopped people from drinking alcohol.

Given the options before us, the candidate which will save the most prenatal human lives is Hillary Clinton given her support for social programs (paid family leave, help with child care, etc.) which make it easier for women to choose to keep their children.

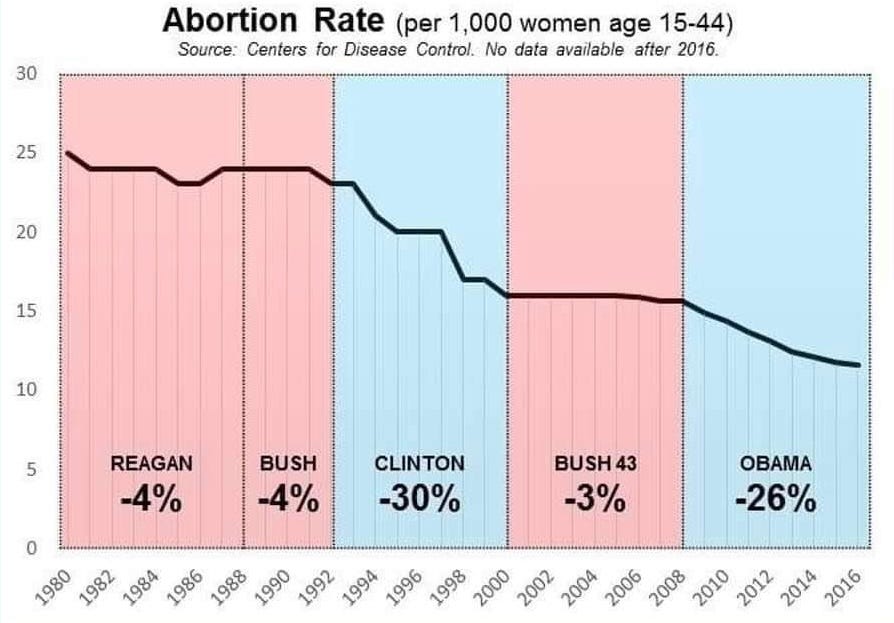

Others condemned such thinking, arguing that nothing could be proportionate to more than a million deaths a year—and that’s when I had to confront the extent to which this is a red herring, because the electoral victory of any one anti-abortion candidate, let alone Trump, was never going to save a million lives a year, or half a million lives, or anything like it. Abortion rates don’t go drastically up or down based on the pro-abortion or anti-abortion views of the person in the Oval Office.

On the contrary, some pro-life advocates of voting Democratic have pointed (also less than convincingly) to a historical correlation of abortion rates apparently falling faster during the Clinton and Obama years than during Republican administrations—and in fact rising for the first time in three decades during Trump’s administration. The argument goes that Democratic policies relieve economic pressures and other circumstances that lead poor women to choose abortion.

This argument isn’t the slam-dunk it seems, for reasons ranging from the spottiness of the data to the causal fuzziness. Still, anything remotely resembling such a correlation, rather than the opposite correlation, at least blunts the prima facie force of the “What could ever be proportionate?” question.

More telling to me was, and is, the question of moral credibility and persuasion. As I have always seen it, the pro-life movement stands or falls with its commitment to the moral high ground. Pro-lifers can’t bully their way to victory; a culture of life cannot arise from lies, insults, divisive and dehumanizing language, encouragement of political violence, and the like. (I can almost hear some of my right-leaning brothers and sisters formulating tu quoque responses: What about the lies and insults and so forth coming from the Democrats? Without endorsing the moral equivalence implied in this rejoinder, I’ll simply say: Friends, who is looking to the Democrats to build a culture of life? I’m talking about the consequences of embracing Trump as a champion of our cause. The defeat of Trump by someone who never pretended to be “pro-life” is not that kind of problem.)

A candidate who is also an issue

In 2016 I was ordained a deacon. I have spoken freely about my political opinions prior to ordination (many of them a matter of public record for a sufficiently determined person with good Google skills). Clergy, though, are called to serve all the faithful—and this means at least muting divisive opinions on topics of legitimate differences of opinion. What exactly this should look like is a difficult question calling for prudential judgment.

As a homilist at Mass, I do my best to have no personal opinions at all—only the faith commended to me by the Church: belief in God in Christ, in the scriptures, and in Church teaching. Outside the pulpit, I speak as a Catholic, but only for myself, not for the Church. Still, I want to be able to speak as helpfully and constructively as possible to as wide a slice of humanity as I can without raising unnecessary obstacles or giving unnecessary offense. Indeed, I am trying to do so, within the bounds of the possible, in this essay! Of course it isn’t possible to engage absolutely everyone at the same time, nor should one try.

As strongly as I believe that the correct amount of killing is zero, I recognize that fundamentally decent, sincere people, including Christians, disagree with me about abortion and other basic moral issues. Some such people are among my friends—and I have more in common with them than with a certain kind of anti-abortion partisan who effectively dehumanizes entire classes of people, from undocumented immigrants and death-row inmates to people who disagree with them politically. There are, of course, people of very different beliefs who also dehumanize those who disagree with them. There are people of various kinds I can’t be friends with because I can’t consider them to be remotely decent people, and people I can’t be friends with because they don’t consider me a remotely decent person. I’m trying to doing the best I can. I hope most other people are too.

Since becoming a deacon, I would rather talk about concrete moral issues than endorse or disparage particular candidates. What I feel I can’t ignore, though, is the unique sense in which Trump, both as a candidate and president, has made himself an issue—an issue with moral implications about which I feel I can’t be silent.

Trump has fostered a cult of personality around himself unprecedented in my lifetime. During the 2008 campaign I was dismayed by the messianic overtones around Obama’s candidacy, but the phenomenon of Trump messianism dwarfs Obama messianism to the point of triviality. Within his administration and the government he insisted on personal loyalty to himself above all and purged officials who put their duties to the Constitution and the law above their loyalty to him. In the wake of national disasters he told governors of states in need of federal support to “ask me nicely.” The unprecedented volume and magnitude of his constant lies overwhelmed fact-checkers and voters’ critical powers, pressing leaders and voters to make a fundamental choice between Trump or the truth. Since the 2020 election, Trump has sought to make support for his false claims that the election was stolen a litmus test for Republican leaders.

These aren’t the only grave issues with his administration, or necessarily the worst. (The worst of Trump’s actual policies might be the systematic family separations at the border, disrupting thousands of families with no plan to reunite them or even track them, along with his policy of deporting undocumented immigrants no matter how long they had been here, whether they arrived as children or even infants.) But they are among the ways in which Trump uniquely made himself an issue in elections and in government.

One unavoidable complication in this narrative for pro-lifers is the overturning of Roe v. Wade—a holy grail for the pro-life movement. From a pro-life perspective, there is no doubt that the overturning of Roe, in itself, is an unqualified good. No law or legal decision permitting the wrongful taking of human life has any legal or moral validity. I also agree with the many legal critics of Roe who found it poorly reasoned and without even nominal Constitutional validity—among the worst Supreme Court decisions of all time, along with Dred Scott, Buck v. Bell (the 1927 pro-eugenics decision that included Oliver Wendell Holmes’ infamous opinion that "three generations of imbeciles are enough”), and Korematsu (the 1944 decision upholding the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII).

The 2022 decision Dobbs v. Jackson, which overturned Roe, was fundamentally correctly decided in my view. This 5–4 decision depended on all three of President Trump’s Supreme Court nominees, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanagh, and Amy Coney Barrett. This means that it also depended on Senate Republicans first blocking President Obama’s nominee Merrick Garland for most of Obama’s last year in office and then rushing in Amy Coney Barrett during the final weeks of Trump’s term. It seems reasonable to me to charge Democrats with pioneering the politicization of the Supreme Court confirmation process with the nomination of Robert Bork—but the last nonpartisan confirmation process was for a Republican nominee, John Roberts, and since then Republicans have been the worst offenders.

In the process of getting the Court they wanted, Republicans engaged in chicanery constituting such a profound challenge to the legitimacy of the process that it would be hard to critique any Democratic response as clearly unjust, including packing the Court if they have the power to do so. (This would be, I think, an imprudent escalation, but not a clearly unjust one.) That’s before we get to health consequences of anti-abortion laws drafted without adequate attention to real-world medical realities. In a truly just society, I believe that unborn lives would be enjoy the same legal protections as all members of society. It doesn’t follow that every anti-abortion law makes society more just.

As elated as pro-lifers were and are about seeing Roe overturned, today many feel that Trump and the 2024 GOP have thrown the pro-life movement under the bus, leaving pro-lifers conflicted about whether to stick with Trump as the least bad option or to wash their hands of both parties this time around. Some pro-life Christian conservatives are again making arguments in favor of voting for Trump’s opponent, Kamala Harris.

My brief, in brief

As in 2016 and 2020, I will not be endorsing any candidates now or in the future. Trump, though, remains a unique figure on the national stage, with unique consequences, and it seems to me reasonable and prudent to share and argue my opinion accordingly.

In case it isn’t already clear, I believe that the defeat of Trump in 2024 is in the best interests, not only of the country, but also of the Republican Party, the pro-life movement, and American democracy. I make that argument in the essay linked below.

Read next: A referendum on elections: Why defeating Trump is the best move for the US and the GOP

I do not have to always agree with you, or with everything you say (well, if I could, we'd be the same person, wouldn't we?), to appreciate your monumental thoughtfulness and expressiveness. Plus the whole excellent-writing thing.

This was brilliant. You covered all the bases, which I have never seen any one else do.