A referendum on elections: Why defeating Trump is the best move for the US and the GOP

[LONGREAD: Of all reasons to oppose either candidate, the dangers specific to Trump are the battle most likely to be significantly won—or lost—in 2024]

See also Reflections on voting as a pro-lifer: Preamble to a Trump polemic

“I think of voting as a chess move, not a valentine.” I’ve seen both left-leaning and right-leaning Catholic friends on social media quote variations on this line from writer Rebecca Solnit—an indication of the conflict that many voters feel in almost any election, including this year’s presidential contest between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris. Few voters ever feel entirely reconciled to either party or its candidates, even if they consider one so much worse than the other as to be no contest.

The virtues of the chess metaphor for voting go beyond this obvious point. Among other things, the consequences of a chess move are usually beyond the power of any human being to fully foresee. Given a sufficiently developed game, every player at every turn is presented with challenges that may be similar to situations they’ve seen in other games, but are never exactly the same. Good players look to improve their position in concrete ways and rely on intuition for the rest.

Likewise, no one can foresee all that will follow for good or for ill based on the outcome of any election. There are scenarios of varying levels of plausibility, for good or ill, for both sets of outcomes, but the most plausible extrapolations aren’t always what actually happens. Still, we try to make the best choices we can based on the issues we consider most important, or most importantly in play.

As a faithful Catholic, I well understand why many US Catholics and other Christians have long considered the Republican Party to be the only game in town (see my previous piece). I’m not here to tell anyone who to vote for, nor am I here to rehearse all the pros or cons of either candidate—an effort for which I would need at least a book.

My brief here is more modest: I want to try to persuade conservative-leaning voters who are at least conflicted or ambivalent about Trump that the defeat of Trump in 2024 is in the best interests, not only of the country and American democracy, but also of the Republican Party and the pro-life movement. By implication, I also contend that Catholics and other Christians can, and I believe should, oppose Trump’s candidacy and make their voting decision accordingly.

I’m not forgetting that Harris stands for many issues that I strongly oppose—issues, I would add, that are bigger than Harris or Trump; bigger, in fact, than the next presidential administration. A Harris administration may well be effective in some ways I oppose (while also doubtless doing things I support), and a second Trump administration may well accomplish some good things (along with things I oppose, some of which Trump has already promised). This is where complexity and unpredictability outrun the scope of this essay. What beliefs and intuitions I have regarding the likely sum total of good and evil resulting from Harris or Trump as president, I will not argue them here; this is not an essay about everything!

In passing, for what it’s worth, I believe that Trump’s bullying, lying, ignorance, and corruption have done more to alienate persuadable Americans from causes I care about, including the pro-life cause, than any Democratic president could have done. Indeed, part of the reason Trump is now distancing himself and the party he leads from pro-life principles is that he doubtless knows he left the pro-life movement weaker than he found it. I believe, too, that embracing Trump has damaged the credibility of US churches generally and is helping to drive American flight from religious affiliation. I believe that when Christians try in desperation to seize the reins of power at any cost, by any means necessary, we experience the debilitating antithesis of the ancient Christian writer Tertullian’s boast that “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.” The Church today is no longer young David, but Saul’s armor still suits us ill.

None of that, though, is my argument in this essay. These are beliefs and intuitions, too difficult to argue in a compelling way to anyone not inclined to see it. (Also out of scope: the opinions of unconflicted Trump supporters who believe that their man is a virtuous patriot selflessly seeking to serve the country, or who consider the 2020 election probably or definitely stolen. I can only do so much in one piece, even one this long.)

My case in this piece is focused on just one defining aspect of the problem of Donald Trump and Trumpism: namely, his sustained pattern of vigorously undermining multiple US elections, both

by falsely denouncing them as “rigged” and “corrupt” before they happen and/or “stolen” after they happen, and

by his own efforts and those of his allies and supporters to develop methods and tools for thwarting election outcomes.

This is far from the only serious problem with Trump, but it’s the one I will argue here.

Trump’s years-long, norm-shattering campaign of election denial and election-thwarting efforts—a set of tactics I’ll discuss at length, for the sake of brevity calling them “anti-electionism”—has significantly changed both how Republican voters think and how other Republican leaders and candidates act, doing serious harm to Republican culture across the board, and thus to American democracy. Crucially, Trump is at the center of this harm, as neither Harris nor any single Democrat is at the center of harm that might reasonably be foreseen from the Democratic Party. Trump’s defeat or victory in 2024, therefore, has the potential to significantly discredit, or decisively vindicate, his methods in a way that Harris’s victory or defeat is unlikely to be similarly decisive regarding any Democratic issue or concern.

This is the crux of my argument: There is no similarly important battle that is as likely to be significantly won or lost in this election cycle as the battle over Trumpian anti-electionism. Effectively, as much as any election has ever been a referendum on anything, the 2024 election is a referendum on elections: on whether we want functional elections or dysfunctional election denialism and election-thwarting tactics. It is not a referendum on the platforms of either party or any planks thereof (issues too large and too deeply rooted in opposing cultures for a referendum in any one election). To extend the chess metaphor, this election is about whether we want to try to play chess by the rules at all.

To be able to fight for anything else, including life issues, we need reasonably functional democracy—like we had before Trump. Trumpism in the GOP is a direct and grave threat to functional democracy: not the only threat, but the one most in play in the 2024 election.

Let’s look at how we got where we are.

The “old normal” and the origins of Trumpian anti-electionism

Back in 2012, when it became clear that President Barack Obama had won reelection, Mitt Romney did what all losing presidential candidates of both major parties had done for decades: After making a concession phone call to the winner, he made a gracious concession speech congratulating his opponent on his victory, affirming his faith in American democracy, and emphasizing the importance of acknowledging the leader chosen by American voters.

Meanwhile, the chairman of the Republican National Committee—a man with the improbably patrician name of Reince Priebus—called for a “full autopsy of what happened, what we did well and what we didn’t do well, what we can do better in the next year.” Priebus later said that he wanted the “autopsy” to be “honest” and “raw.” The resulting 100-page document, called the “Growth & Opportunity Project,” offered a number of criticisms of the way the GOP had been engaging on the national level that the report said was marginalizing the party and cutting itself off from people who agreed on some issues but not others. The party had become far too synonymous with rich white men, the report said, and needed to work harder to reach out to women and minorities and to pursue greater diversity within the GOP. It also needed to show concern for poorer Americans and embrace immigration reform.

In short, Republicans in 2012 had no problem forthrightly acknowledging that they had lost an election, and even that losing two consecutive elections was a reality check that Republicans needed to take responsibility and adjust course in order to do better. This was, in principle, a responsible, appropriate way for a major political party to respond to repeated losses in the polls. (How candidly self-critical the report actually was, and to what extent the GOP sought to follow its recommendations, are of course separate questions.)

In acknowledging electoral defeat and fully supporting the peaceful transition of power (in this case from a first term to a second term), Republicans were doing what was expected and what had overwhelmingly happened in all modern US elections. (What about 2000? I’m glad you asked! Stay tuned.)

At the same time, in 2012 there was another voice—not yet nearly so prominent in GOP circles as it would soon become—with a very different message.

Although he had endorsed John McCain in 2008, Donald Trump also initially defended President Obama, whom he called “a champion” and “a strong guy” who “knows what he wants, and this is what we need.” As late as September 2010, Trump credited Obama with saving America from a depression. Less than two weeks later, Trump suggested that he was thinking about running for president against Obama in 2012. In April 2011 Trump went on Fox News to call Obama America’s “worst president ever.”

Trump wound up not running against Obama in 2012, though he did all he could to undermine Obama by pushing the birtherism conspiracy theory that Obama hadn’t really been born in Hawaii and thus was supposedly ineligible to serve as president. When Obama again won both the electoral vote and the popular vote (this time by nearly five million ballots), Trump went ballistic on Twitter. From his election-night tweetstorm:

“The electoral college is a disaster for a democracy.”

“We can’t let this happen. We should march on Washington and stop this travesty. Our nation is totally divided!”

“Lets fight like hell and stop this great and disgusting injustice! The world is laughing at us.”

“This election is a total sham and a travesty. We are not a democracy!”

“Our country is now in serious and unprecedented trouble...like never before.”

“Our nation is a once great nation divided!”

“He lost the popular vote by a lot and won the election. We should have a revolution in this country!”

“More votes equals a loss … revolution!”

Although comparatively few people were paying attention at the time, this pattern would become familiar over the next decade:

repetition of factually false election-outcome claims, as if reiterating a lie enough times makes it true

attacks on the validity of the election outcome

attacks on the institutions of American democracy

claims of an unprecedented crisis; allegations that other nations are “laughing” at the US

calls for direct action to thwart the outcome of a legitimate election, up to and including repeated calls for “revolution”

Unlike the responses from Romney and Priebus, Trump’s angry, reality-denying, would-be revolutionary response to the 2012 Republican defeat was not the way that any major political figure at that time would speak. In 2012, the peaceful transition of power after an election was taken for granted by the leadership of both parties as an essential hallmark of a healthy democracy, a fixture of US politics taken for granted by all Americans.

All of that would change in the decade to come.

What we need and where we are

Among the most basic requirements for a reasonably functional democracy is a well-founded confidence in the election process. A healthy democracy is one in which citizens can and should have significant and appropriate belief that the following are true:

Qualified citizens who wish to exercise the right to vote will be able to do so.

Ballots are collected in a secure manner and reliably counted and certified, so that the certified results reflect, to highly accurate degrees, the actual numbers of legitimate votes cast, without significant distortion either from miscounting of legitimate votes or addition of fraudulent votes.

Election outcomes will be reliably followed by the peaceful transition of power, whether from one political party to another or from one administration or term to another.

Without all of these conditions—and substantial confidence in them by a healthy majority of citizens—democracy is compromised and potentially at risk.

Americans have not always had healthy democracy. Elections in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, particularly at state and local levels, were vulnerable to election fraud and theft. Even at the national level, the 1876 presidential contest between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel J. Tilden, in the wake of the Civil War, was marred by rampant tampering on both sides, with pro-segregation Democrats seeking to suppress the Black vote through intimidation and progressive Republicans engaging in ballot-box stuffing, repeat voting, and discarding of Democratic ballots. Into the twentieth century, women were not permitted to vote until 1920 and Black Americans were not guaranteed the right to vote until the mid-1960s.

Today, of course, we tend to think of ballot box stuffing and the like as charges leveled by Republicans against Democrats, and of suppression of minority votes as charges leveled by Democrats against Republicans. Party labels and alignments aside, we can speak broadly throughout American history of concerns about election security on the political right (i.e., guarding against fraudulent ballots and subversion of the counting process) and of concerns about free and fair access to voting on the political left (i.e., guarding against citizens being unjustly excluded or deterred from voting). These varying concerns accord with the general tendency on the left to think of justice primarily in terms of pursuing fairness while the right tends to think of justice primarily in terms of maintaining order. (Both principles are of course per se valid; we need both order and fairness!)

Distrust in government and institutions generally is nothing new for Americans. The world in which I grew up was shaped by political and social unrest in the 1960s and 1970s, assassinations of leaders from JFK to MLK, the Vietnam War and the Pentagon Papers, and the Watergate scandal. Public officials have widely been seen as selfish and unconcerned about average Americans—attitudes that have waxed and waned over the decades, often varying with the party in power at the moment. In particular, American confidence in election integrity across the country tends to rise or fall somewhat among voters depending on whether their party won or lost the last election.

Still, according to polls, in recent decades most Americans have viewed elections with more confidence than not—until, that is, the last four years, when election confidence levels among Republicans crashed to all-time lows, for reasons having nothing whatsoever to do with reality.

From the Bush administration through Obama’s two terms and into the 2016 election, Gallup polling found that Republican confidence in proper casting and counting of ballots never dropped below 55 percent, even spiking to 77 percent ahead of the 2018 midterms with Trump in office. In 2020, though, Republican election confidence plummeted to a record low of 44 percent, and sank even further in the 2022 midterms to just 40 percent. (Among Democrats, by contrast, Gallup found that election confidence levels never dropped below 57 percent.)

Regarding the 2020 election, a January 2021 Pew Research poll found that a whopping three-quarters of Trump voters believed that Trump definitely or probably won the 2020 election, with 40 percent saying they were sure of it. Only 7 percent of Trump voters were sure that Biden had really won. Subsequent polls have continued to find that large majorities of Republicans consider the 2020 election illegitimate. A 2023 Monmouth poll found that 68 percent of Republicans (not just Trump voters) said Biden won “due to voter fraud.”

Regarding the looming 2024 election, last year an Associated Press–NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll found that, compared to 71 percent of Democrats, an astonishingly low 22 percent of Republicans were highly confident that votes in would be counted accurately—down from 28 percent shortly before the 2020 election and 32 percent before the 2016 election.

These cratering numbers (from multiple polling organizations) are not normal, and do not correspond to reality: namely, that modern US elections are highly secure, voter fraud is vanishingly rare, and the 2020 election in particular was “the most secure in American history” (more on this later). Trump is not solely responsible for the dismal state of Republican confidence in US democracy; indeed, he is partly a symptom of it. Still, his pattern of sustained anti-electionism has contributed uniquely and mightily to the problem. (Trump defenders sometimes cite a small number of supposedly similar cases of prominent Democrats calling elections “stolen” or “illegitimate,” but, as we will see, there is no comparison—and this is reflected in the consistently higher levels of election confidence among Democratic voters.)

Trump hasn’t just shaped perceptions about elections among Republican voters. He has also profoundly transformed attitudes, rhetoric, and behavior regarding elections among Republican leaders. Prior to his presidency, top leaders of both parties generally adhered in public stances and statements to the expectation that election outcomes must be acknowledged, at least in theory and in principle, as the manifest expression of the will of the people. After Trump’s presidency, by contrast:

2020 election denialism has become well established among Republican leaders and candidates.

Republican leaders and candidates are also increasingly comfortable refusing to commit to accepting election outcomes, including in the 2024 presidential election.

Efforts to thwart election outcomes—including local officials who are prepared to obstruct certification of Democratic majority electoral outcomes—are no longer unthinkable. On the contrary, Republican efforts to discredit the 2024 election before it happens and to contest or thwart it if they lose are in full swing.

The Republican National Committee, co-chaired by Trump’s daughter-in-law Lara Trump, is questioning job seekers in battleground states on whether they believe the 2020 election was stolen.

In a word, Trump has fostered a new culture of political engagement on the right that blatantly puts party above democracy and rule of law. These trends are dangerous—and mutually reinforcing. A world in which large numbers of Republicans increasingly disbelieve in election integrity is a world in which more local Republican officials will be willing to work to subvert election outcomes. By the same token, election-thwarting efforts by Republican officials will tend to be construed by Republican voters (assuming that where there’s smoke there’s fire) as confirmation of Trumpian claims of voter fraud.

Test cases of the “old normal”: The 1960 and 2000 elections

A world with more than one major party that is committed to the smooth functioning of democratic elections—that expects its candidates to pledge to accept election results; that regularly tells voters the truth about elections; that upholds the peaceful, uncontroverted transition of power—is not an idealistic pipe dream. By and large, both parties met this standard for many years before Trump, and Democratic party leaders are still basically committed to the smooth functioning of democracy.

This is not because Democratic leaders are inherently more honest and virtuous or less corruptible than Republican leaders! Rather, so far as I can see, the smooth functioning of democracy has always been in the best interests of both parties, members of whom have historically benefitted from the system regardless of which party controlled the White House or either branch of Congress in any given year. Trying to defy or steal a modern election is tantamount to trying to break the system—and breaking the system is difficult, risky, and not in either party’s best interests. Because of this, it makes sense for the culture of power historically shared by both parties to promote this mutual interest in maintaining the system.

Consider how the system worked in the last couple of times genuinely ambiguous circumstances in a presidential election potentially threatened a constitutional crisis: in 1960 and in 2000. Via the National Constitutional Center website, from an article the Constitution and the peaceful transition of power entitled “Nothing less than a miracle”:

In 1960, John F. Kennedy, the Democratic senator from Massachusetts, and Richard Nixon, the Republican Vice President, were locked in a tight battle through Election Day. Overnight, the election was called for Kennedy by a comfortable Electoral College vote of 303 to 219, but a narrow margin of 112,000 in the popular vote. Rumors quickly spread that voting in Illinois and Texas had been manipulated by Kennedy forces; Nixon supporters urged their candidate to contest the results. But Nixon conceded peacefully, telling a friend that “our country cannot afford the agony of a constitutional crisis.”

And in 2000, George W. Bush, the Republican governor of Texas, narrowly led Al Gore, the Democratic Vice President, in Florida after the first results were tallied, thus triggering an automatic statewide recount. After a machine recount revealed an even narrower lead for Bush, a legal battle ensued over the scope and method of further hand recounts, with teams of opposing lawyers swarming the Sunshine State. The dispute ultimately reached the Supreme Court, which ruled the hand recounts unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment. Despite calls from his supporters to continue the fight, Gore conceded peacefully, saying, “While I strongly disagree with the Court's decision, I accept it.”

In Gore’s case, notably, although he appealed to the courts to support his recount efforts, he filed no lawsuits, cast no aspersions at election officials or judges, and made no allegations of corruption or election theft. (I can find no evidence of Florida election workers receiving death threats in 2000, in sharp contrast to election workers in the wake of the 2020 election.) In fact, on January 6, 2001, in a joint session of Congress to certify the electoral vote, when 20 Democratic representatives rose to file objections to the electoral votes in Florida (mostly members of the Congressional Black Caucus, as many rejected ballots came from largely Black communities), Gore ruled these objections out of order (on the legal grounds that none of them were co-sponsored by a senator).

In his self-deprecating concession speech, Gore quoted Stephen Douglas’s concession to Abraham Lincoln, making the words his own: “Partisan feeling must yield to patriotism. I’m with you, Mr. President, and God bless you.” He also called on all Americans to join him in supporting the new administration:

Just as we fight hard when the stakes are high, we close ranks and come together when the contest is done. And while there will be time enough to debate our continuing differences, now is the time to recognize that that which unites us is greater than that which divides us. While we yet hold and do not yield our opposing beliefs, there is a higher duty than the one we owe to political party. This is America and we put country before party; we will stand together behind our new president.

The concession speech is an important ritual of the peaceful transition of power in modern US politics. In the apt words of historian and political theorist Paul Corcoran, a concessions speech is “an institutionalized public speech act integral to democratic life and the legitimacy of authority.” It embodies the commitment of both major parties to the democratic process and helps guide supporters to accept unwelcome election outcomes.

I have no brief for either Nixon or Gore as great politicians or men of great character. What I can say is this: At singularly challenging moments in ambiguous election processes, both men recognized what was expected and required of a public servant who puts country before party and party before self, and they rose to the challenge. That is the old normal. That’s how the system should work.

Other losing presidential candidates, both Republican and Democratic, have likewise cleared the bar set (somewhat lower) for them. Hillary Clinton, in 2016, cleared the bar in her own concession speech—which, given the uniquely ungracious and problematic character of her opponent, possibly rivaled Gore’s in its level of difficulty. Among other things, Clinton said she hoped Trump would “be a successful president for all Americans,” and said to her followers:

I still believe in America and I always will. And if you do, then we must accept this result and then look to the future. Donald Trump is going to be our president. We owe him an open mind and the chance to lead.

It is true that Gore and especially Clinton, years later, made disgruntled and unwise (if isolated) comments about these elections. Gore said in 2002 that he believed he would have won “if everyone in Florida who tried to vote had had his or her vote counted properly,” though he again reiterated, “But I respect the rule of law, so it is what it is.” More damagingly, speaking as secretary of state in 2009 in the context of election corruption in Nigeria, Clinton said, “In 2000, our presidential election came down to one state where the brother of the man running for President was the governor of the state. So we have our problems too.” In 2019 Clinton called Trump “an illegitimate president” in connection with allegations of tactics like “voter suppression and voter purging.”

I am not saying that the Democratic record of publicly upholding the integrity of every election is perfect. But there is no comparison to Trump’s sustained, reality-defying campaign against the integrity of the democratic process in one election after another—or, in 2020 and 2021, his attempts to reverse the 2020 election outcome.

Trump’s inability to accept even the one election he actually won

It should be obvious to anyone with eyes to see that the bar of graciousness in defeat, of putting country before party and party before self, is a bar that Trump is incapable even of aspiring to clear, let alone clearing. Not only that, even in victory Trump was unable, in 2016, to clear the far lower bar of acknowledging the validity of election results that gave him an electoral college win—because he couldn’t accept losing the popular vote by nearly three million ballots!

Already ahead of Election Day 2016, Trump’s attacks on the election as “rigged” had an enormous impact on voter perceptions. An October 2016 POLITICO/Morning Consult poll found that a whopping 73 percent of Republican voters were concerned that the 2016 election might be “stolen” from Trump. During the campaign Trump repeatedly indicated that he would accept the election results “if I win” and called the election “rigged” against him—language that President Obama rightly warned against:

That is dangerous. Because when you try to sow the seeds of doubt in people’s minds about the legitimacy of the elections, that undermines our democracy. Then you’re doing the work of our adversaries for them.

A number of Republicans supporting the old normal likewise criticized Trump’s preemptive defiance. House Speaker Paul Ryan stated, “Our democracy relies on confidence in election results, and the speaker is fully confident the states will carry out this election with integrity.” John McCain, who had practiced what he preached in his own outstanding 2008 concession speech, said:

I didn’t like the outcome of the 2008 election. But I had a duty to concede, and I did so without reluctance. A concession isn’t just an exercise in graciousness. It is an act of respect for the will of the American people, a respect that is every American leader’s first responsibility.

Trump fired back:

Of course there is large scale voter fraud happening on and before election day. Why do Republican leaders deny what is going on? So naive!

In the end, Trump couldn’t even live up to his self-serving “pledge” to accept the election results “if I win.” His loss of the popular vote triggered the reality-defying election-denialist streak first seen in 2012, marking perhaps the first time in American history to date that a candidate in any major race resentfully alleged massive voter fraud despite winning the election. It began, as Trump’s claims often did, on Twitter:

In addition to winning the Electoral College in a landslide, I won the popular vote if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally

Serious voter fraud in Virginia, New Hampshire and California - so why isn’t the media reporting on this? Serious bias - big problem!

Actually, it probably began on the radio show of conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, who claimed without evidence that three million undocumented immigrants had voted in the 2016 election. (Trump later inflated this to three to five million in his first official meeting with congressional leaders in January 2017.) Trump had appeared on Jones’s show during the campaign and praised his work. (Jones has advanced numerous odious conspiracy theories, the ugliest of which was the claim that school shootings like Sandy Hook Elementary were hoaxes, that no children were killed, and that grieving parents were “actors.” His lies resulted in years of harassment and death threats against families of children killed in school shootings. Jones was successfully sued for a $1.5 billion settlement for his unconscionable lies, and his assets have been ordered to be sold to settle his debts.)

At that time Trump’s pattern of election denialism was still considered unacceptable enough that some Republican leaders took exception. For example, Lindsey Graham scolded Trump for undermining American confidence in our democratic system:

To continue to suggest that the 2016 election was conducted in a fashion that millions of people voted illegally undermines faith in our democracy. It’s not coming from a candidate for the office, it’s coming from the man who holds the office. So I am begging the president, share with us the information you have about this or please stop saying it.

During the 2016 campaign, more responsible Republicans had talked hopefully about “holding Trump accountable” as president. Yet any hopes of whipping Trump into more presidential behavior backfired spectacularly: Instead, Trump quickly began to remake the Republican party in his own image, changing popular thinking about what was acceptable and possible through his willingness to defy norms and do things previously considered unthinkable and unacceptable.

On a side note, even before the 2016 election, during the primaries, Trump falsely claimed that his loss in the Iowa caucuses to Ted Cruz was due to fraud:

Ted Cruz didn’t win Iowa, he stole it. That is why all of the polls were so wrong and why he got far more votes than anticipated. Bad!

Based on the fraud committed by Senator Ted Cruz during the Iowa Caucus, either a new election should take place or Cruz results nullified.

No loss is too small for Trump to resent and lie about! This may seem trivial, but 10,000 little lies pave the way for the big lie.

The 2020 election: War on democracy

In the 2018 midterms, Trump again leaned into unfounded election-fraud alarmism, both before and after the elections. By 2020, Trump had broken so many norms (among other things, repeatedly toying with the idea that he should get more than the constitutionally permitted eight years in office because the Russian election interference investigation supposedly “stole” two years from his first term), and attacked the integrity of US elections so relentlessly, that few people in either party even expected him to accept defeat, no matter how decisive the results might be.

In part because of the coronavirus pandemic, many states had changed their policies to increase voting by mail—a development Trump blasted amid an avalanche of misinformation: “This is going to be a fraud like you’ve never seen.” Once again Trump refused to pledge to accept the election results—this time as the incumbent refusing to commit to the peaceful transition of power. Other Republicans tried to resist this, as when Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell tweeted, “There will be an orderly transition just as there has been every four years since 1792.” Nebraska Senator Ben Sasse said more bluntly, “The president says crazy stuff. We’ve always had a peaceful transition of power. It’s not going to change.” (Sasse was correct about Trump’s propensity for crazy talk—a complex topic in itself, not so easily dismissed as many Trump supporters want it to be—but these optimistic predictions were far from fully borne out, and certainly Trump did everything in his power to thwart them.)

The 2020 election results were not close. Within a few days of the November 3 election, it was clear that Biden was the winner; within a week it was clear that he would win with 304 electoral votes to 232. While several states were still counting votes, the margin in the closest states was more than 10,000 votes—and Biden’s victory would not have been threatened by the hypothetical loss of even multiple close states.

Trump’s response to the 2020 election outcome was an all-out assault, using every tool at his disposal, on the legitimacy of the election—an assault that continues to this day. In a televised address, he lied, “If you count the legal votes, I easily win. If you count the illegal votes, they can try to steal the election from us…We won by historic numbers.” This was not campaign-trail rhetoric. This was the president of the United States, speaking from the White House, falsely telling the nation that he had won an election he had lost. Blasting alleged corruption and vulnerability in the system, he went on to say:

Even beyond our litigation, there’s tremendous amount of litigation generally because of how unfair this process was, and I predicted that. I’ve been talking about mail-in voting for a long time. It’s—it’s really destroyed our system.

It’s a corrupt system. And it makes people corrupt even if they aren’t by nature, but they become corrupt; it’s too easy. They want to find out how many votes they need, and then they seem to be able to find them. They wait and wait, and then they find them.

In reality, senior officials at multiple federal and state-level agencies overseeing election security—including Trump appointees, such as acting Homeland Security chief Chad Wolf and Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency director Christopher Krebs—agreed in a joint statement that the 2020 election was “the most secure in American history.” This statement came from the Election Infrastructure Government Coordinating Council (made up of officials from the Department of Homeland Security and the US Election Assistance Commission, state-level election officials, and representatives of the voting machine industry) and from the Election Infrastructure Sector Coordinating Executive Committee. Trump’s reaction included firing Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency director Krebs (via Twitter, as he often did these things).

Trump’s many false claims of election fraud were repeatedly refuted by his own officials, most notably by the Department of Justice’s Attorney General William Barr, another Trump appointee. Despite having been considered a reliable Trump ally who boosted Trump’s pre-election concerns about mail-in voting and in November 2020 approved an investigation into voting irregularities, Barr repeatedly repudiated Trump’s election denialism. (Despite Barr’s many post-election statements of opposition to Trump’s lies and his character, in April 2024 Barr endorsed Trump over Biden!)

In December 2020 Barr stated that the Justice Department had found no evidence of “fraud on a scale that could have effected a different outcome in the election.” In later January 6 hearings, Barr would resort to a thesaurus-level variety of descriptions of the claims from Trump’s legal team regarding election fraud: “completely bullshit,” “absolute rubbish,” “idiotic,” “bogus,” “stupid,” “crazy,” “crazy stuff,” “complete nonsense,” and “a great, great disservice to the country.” Barr also stated that if Trump actually believed the garbage he was spewing about the election, then he had become dangerously “detached from reality.” In a 2023 CNN interview he called Trump’s actions “nauseating” and “despicable,” even saying, “Someone who engaged in that kind of bullying about a process that is fundamental to our system and to our self-government shouldn’t be anywhere near the Oval Office.” He even said in another 2023 interview (again, regarding someone he recently endorsed over his rival at the time):

If you believe in his policies, what he’s advertising is his policies, he’s the last person who could actually execute them and achieve them. He does not have the discipline; he does not have the ability for strategic thinking and linear thinking or setting priorities or how to get things done in the system. It is a horror show when he is left to his own devices. You may want his policies, but Trump will not deliver Trump policies. He will deliver chaos and, if anything, lead to a backlash that will set his policies much further back than they otherwise would be.

(Sorry, that goes beyond the scope of my argument in this essay. Got carried away there.)

Stop the Steal: By hook, crook, and the kitchen sink

The 2020–2021 election outcome reversal effort was a multi-pronged effort subjecting the institutions of American democracy to the gravest test they have faced in modern times and possibly ever.

In addition to the massive propaganda campaign to persuade his followers and vulnerable Americans that the election was fatally compromised by massive election fraud involving a variety of groundless conspiracy theories—rigged voting machines, reams of ballots discarded or added, an international communist conspiracy, etc.—Trump marshaled a team of lawyers to file scores of groundless, frivolous lawsuits challenging massive election fraud, though this claim was seldom made in court and evidence was never presented.

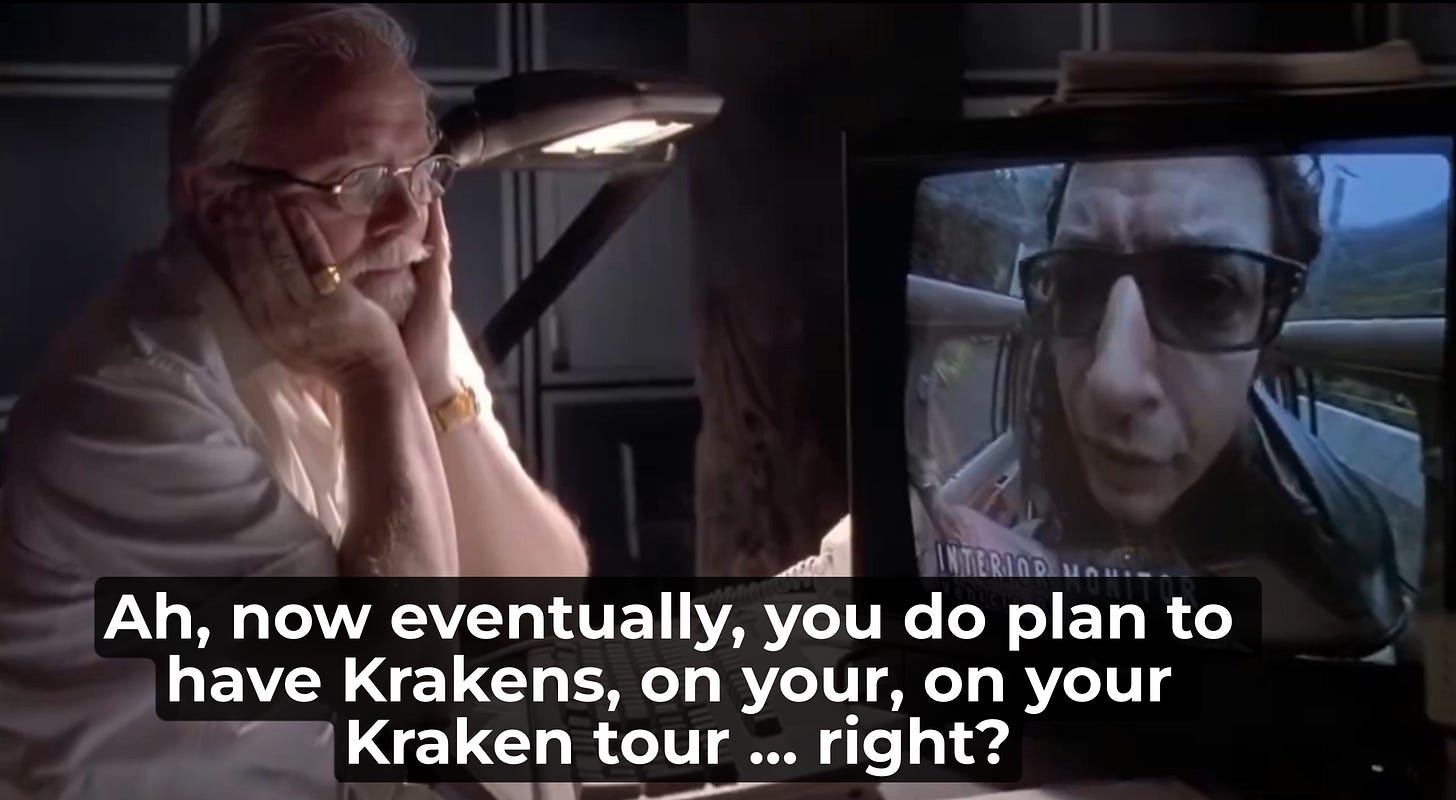

In all, the Trump team filed 62 lawsuits while promising Trump supporters that they had the goods to prove election fraud. “We have so much evidence,” Trump said. “They say, ‘Oh, he doesn't have the evidence.’ We have so much evidence, we don't know what to do with it.” Regarding specific allegations that Dominion voting machines had been rigged, Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani claimed, “We have proof that I can’t disclose yet.” Attorney Sidney Powell, displaying a penchant for colorful metaphors, said, “We have so much evidence, I feel like it’s coming in through a fire hose,” and famously promised, “I’m going to release the Kraken.” (A monster lawsuit? A monstrous amount of evidence? Whatever it was, the Kraken never materialized.)

This was all blowing smoke. In public Trump’s lawyers promised evidence of fraud, but in court, even arguing before Republican-appointed or Trump-appointed judges, election fraud was hardly ever mentioned. In fact, after weeks of failed legal shenanigans, in a lawsuit filed by Texas AG Ken Paxton, joined by the Trump campaign and 17 other Republican AGs, the Trump team argued that the observation that “no widespread voter fraud has been proven … misses the point. The constitutional issue is not whether voters committed fraud but whether state officials violated the law by systematically loosening the measures for ballot integrity so that fraud becomes undetectable.” “Undetectable,” of course, means not only does evidence not exist, it can’t exist! This strategy, too, went nowhere.

In the end, the entire legal effort was a complete wash. Not only did they prove no significant election fraud, they won no significant legal victory of any kind. Of all 62 lawsuits, Trump’s lawyers won only a single trivial, temporary victory, excluding a small number of Pennsylvania ballots cast by voters who tried to validate or “cure” their ballots with required identification after a three-day deadline. Since Biden won Pennsylvania by over 80,000 votes, it made no difference (and the decision was later overturned anyway by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court). That single case aside, every one of the Trump team’s lawsuits failed. Dozens were dismissed after a hearing of evidence on the merits by judges. Others were dropped for lack of evidence or for other reasons, often with judgments like “frivolous” and “without merit.”

Three lawyers involved in the effort—Sidney Powell, Kenneth Chesebro and Jenna Ellis—have pleaded guilty to charges connected with attempts to interfere in the Georgia election. Giuliani lost his law license in 2021 and in 2024 he was disbarred in the state of New York. He has been indicted in Arizona for his role in trying to overturn the 2020 election and successfully sued for defamation by Dominion Voting Systems and another voting company, Smartmatic, and by Georgia election workers, whom he was ordered to pay $148 million. (Giuliani, who has declared bankruptcy, whines that Trump still owes him $2 million, making him one of hundreds of people whom Trump has failed to pay over the years.)

Legal challenges were far from Trump’s only gambit. As of this week, Trump faces revised federal charges for his other efforts to try to thwart the outcome of the 2020 election.

One key tactic involved both public and private efforts to persuade election officials to alter, prevent, or delay vote count certifications both at the local and the national level. Fallout from this focus on election officials has included a massive increase in threats of violence and death against election workers. (Throughout late 2020, I heard Trump supporters say things like “We need to let the process play out” and “The president is entitled to pursue all avenues of inquiry,” apparently on the assumption that if he failed there was no harm done. Frivolous lawsuits and criminal efforts to pressure officials to subvert the election are one thing as long as everyone else does the right thing and no one gets hurt, but we are in very different territory when people just doing their jobs start getting death threats for not knuckling under to the president.)

After the canvassing board for Wayne County, Michigan, voted in favor of certifying local election results, Trump and RNC Chair Ronna McDaniel called the two Republican members urging them not to sign off on the results. Trump’s familiar litany from that phone call: “We’ve got to fight for our country … We can’t let these people take our country away from us. … Everybody knows Detroit is crooked as hell.” He also promised to get lawyers for the two canvassers. The next day the canvassers tried to rescind their votes, to no avail.

In Georgia, The State of Georgia v. Donald J. Trump, et al. is pending against Trump and 18 co-defendants, who are charged under racketeering laws with conspiring to “unlawfully change the outcome” of the election in Georgia. Central to the case is Trump pressuring Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to change the state's election results during an hour-long conference call on January 2, 2021: “What I want to do is this. I just want to find, uh, 11,780 votes, which is one more than we [need to tie], because we won the state.” This was after the votes had been recounted and twice certified. Trump also wrote to Raffensperger claiming that tens of thousands of ballots in DeKalb County were compromised, and that Raffensperger should “start the process of decertifying the election, or whatever the correct legal remedy is, and announce the true winner.” Trump and Giuliani also publicized baseless accusations against two poll workers, mother and daughter Ruby Freeman and Wandrea Moss, accusing them of election fraud. Raffensperger, Freeman, and Moss all received death threats, and the FBI warned Freeman and Moss that they would not be safe in their home.

Members of the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors, who certified Biden’s win in Arizona’s largest county, received multiple calls from Trump, Giuliani, Powell and others in late December and early January. Some of these calls involved attempts to raise baseless questions about counting accuracy. GOP chairman Clint Hickman got two calls from Trump himself, which Hickman, aware of election tampering phone calls to Georgia officials, allowed to go to voicemail. (Hickman said, “I had seen what occurred in Georgia and I was like, ‘I want no part of this madness and the only way I enter into this is I call the president back.’”)

Still another tactic, in which Trump may or may not eventually be charged, was the fake electors plot involving Republican officials in seven states working to create fraudulent documents falsely certifying that Trump had won those states, with Vice President Mike Pence playing a key role in replacing real electors with fake ones or disqualifying entire states from the final electoral count, allowing Trump to be named the winner.

Trump also pressured the Justice Department to falsely declare the 2020 election “corrupt.” Neither Barr nor his successor, Jeffrey Rosen, were willing to cooperate. Trump then tried to elevate a willing official, Jeffrey Clark, to acting attorney general, but backed down in the face of threats of mass resignations by top Justice Department leaders and White House officials.

The January 6th attack on the Capitol—a topic too vast to fold into the end of an essay this long—was the last-ditch gambit to prevent the certification of Biden as the winner. When that failed, Trump briefly lost his nerve and, fearing legal consequences, gave a tortured, scripted concession speech deploring the violence and finally promising “a smooth, orderly and seamless transition of power.” After this initial loss of nerve, Trump later walked back his condemnation of January 6 violence (just as he did in the wake of the Unite the Right rally) and began rehabilitating the attackers.

Rationality vs. drama

Despite all indications to the contrary, many of the Trump faithful continued to believe until January 20, 2021 that Trump would somehow triumph and that Biden would not be sworn in. (Even after January 20, some true believers couldn’t accept that Biden was really president, and bizarre conspiracy theories spread to keep the myth of Trump’s victory on life support.)

Ultimately, every one of Trump’s diverse array of election-thwarting efforts in 2020 and 2021 failed. The system did work—and for the most part it continues to work. That may seem encouraging, but there are two all-important catches. First, while Trump wasn’t able to reverse the 2020 election, the damage to beliefs among Republican voters and behavior among GOP leaders is done, and ongoing. Second, if you keep throwing enough stuff at the wall for long enough, eventually something is bound to stick.

Just because zero Trump-appointed judges handed him victories in 2020 and zero election officials successfully prevented certification of votes doesn’t mean the same thing will happen every time. Outrageous verdicts aren’t the norm, but they do happen. One significant such verdict would be enough to provide a fig leaf for a lot of anti-electionism to come. A small number of well-positioned county or state election officials refusing to certify election results (whether out of allegiance to Trump or buckling in the face of death threats) could be enough to lead to a constitutional crisis. Plan ahead, get enough loyalists in the right positions, and you won’t have to worry about being contradicted by your own officials or facing threats of mass resignations the next time you want the Justice Department to declare an election “corrupt.”

One of the least appreciated lines of defense protecting modern US elections has always been the norms and conventions followed by leaders of both parties who didn’t want to break the system. That line of defense is now compromised, and we may be only starting to learn how robust or vulnerable remaining lines of defense may be.

Trying to break the system has never been in the best interests of either party, rationally speaking—but the thinking in the GOP at present is not rational, because Trump has been doing their thinking for them. His perspective and priorities are entirely different from traditional party leadership and have nothing to do with the long-term interests of either party.

Trump’s willingness to defy norms and do what was previously considered unthinkable is dramatic, and Trump is all about drama. The single most significant factor in Trump’s success in life has always been his instincts for self-marketing and ratings. His “winner” aura was always his most reliable asset, no matter how many businesses he bankrupted or how many millions he cost investors. He is now in the process of ruining the GOP, but as long as his poll numbers are high enough, few GOP leaders will care to take the hit of resisting him for the good of the party, and many will just want to share in the glory while it lasts.

How anti-electionism succeeds or fails

These dangerous trends are not necessarily irreversible.

Trump has already been preemptively declaring the 2024 election rigged and maintaining that the Democrats can win only by cheating. (This week he went to the blasphemous extreme of declaring that he would even win deep-blue California “if Jesus came down and was the vote counter … in other words, if we had an honest vote counter, a really honest vote counter”). If he loses again in November, he will of course forever insist that it was “stolen.” For a while he may try whatever means of fighting the loss may be at his disposal as the out-of-power candidate—including relying on Republican county officials who are prepared to obstruct certification of unwanted results. Election confidence among Republican voters may well sink even lower than it has to date.

Despite this, if Trump is truly defeated, it will very probably spell the end of Trump’s national political career and likely at least begin the process of weakening Trumpist/MAGA influence in the GOP.

Trump is a charismatic figure with a cultlike personal following; there is currently no evidence of any similarly charismatic successor. (Few people will make or circulate messianic memes about JD Vance!) If Trump is defeated again, his already-tattered “winner” aura will fade further—particularly if, as seems likely, his legal and financial woes continue to catch up with him and his ability to communicate effectively continues to deteriorate. At that point, he will be a two-time loser who never won a popular election and who has always failed as a known quantity. His following may never die, but it will probably irreversibly begin to decline.

While Trumpist provocateurs like Lauren Boebert, Marjorie Taylor Greene, and Matt Gaetz will MAGA on, post-2020 experience suggests that GOP leaders who tried to stay out of the way of Trump and his followers, and even those who opportunistically went along for the ride as long as Trump was powerful and effective, will be on the lookout for ways to chart a post-Trumpian course for the GOP. Voices of dissent criticizing the harmful effects of Trumpism on the party will become more common. There are no guarantees, of course, but a post-Trumpian and even Trump-critical new chapter for the GOP might open the door for a gradual return to pro-democratic, election-affirming norms and an increasingly functional Republican party.

What happens, on the other hand, if Trump wins again in November? For his followers and the vast majority of Republican leaders, it will be a resounding vindication of Trump’s methods and his message—above all his response to his 2020 defeat. It will establish decisively that Trumpian anti-electionism is not only not a disqualifying strike against a candidate, but is a savvy response to defeat, and is rewarded with loyalty, support, and victory. It will revitalize the MAGA movement as the life and future of the GOP and weaken any remaining Republican elements of resistance to Trumpism.

A Trump victory will virtually guarantee that, whatever the next four years holds, the best-case scenario we can reasonably hope for in 2028 is a GOP candidate like Vance running with loud pre-election warnings about election fraud, vowing that they will win if the election is fair and lose only if it is stolen. Even if Democrats win in 2028, 2020’s stop-the-steal election-thwarting efforts will almost certainly look like a dress rehearsal for the election reversal project MAGA activists will have spent eight years preparing. Anti-electionism will also spread at the state and local level.

If this happens—if Trumpian anti-electionism continue to spread among Republicans, threatening election outcomes and being rewarded by voters—it is all too likely that frustrated Democrats will eventually begin to respond by tolerating and even encouraging discreditable tactics on their side to twist election outcomes in their own desired directions. How could they not? At this point, if not well before, America will face a constitutional crisis unlike anything we have ever seen.

As terrifying as these prospects are, a certain kind of Trump supporter may actually relish them, even invoking notions of “civil war.” Whether or not it ever comes to violence, I can think of no more plausible path to the failure of the American experiment—certainly no such path as likely to turn on the outcome of the 2024 election—than the proliferation of anti-electionism.

A post-Trumpian world

A well-known saying holds that “You go to war with the army you have.” It’s a good saying, but an important caveat is that there are indispensable rules even in war. If the army you have has developed a penchant for routinely ignoring and flouting the most fundamental rules, then, given a reasonable chance of getting a better army in the long run, it may be well worth losing a battle for that chance.

A chance. That’s all we have to go on. These are all probabilities. As I noted at the outset, the most probable outcome isn’t necessarily one that happens. It could be that the institutions of American democracy are strong enough, even if Trump wins a second term, to fend off a third round of presidential anti-electionism in 2028, and that the GOP will eventually normalize on its own. I’d like to think that’s true, but I also hope it isn’t put to the test, in the same way that I hope I don’t have to find out if my airbags deploy in a crash.

Conversely, perhaps the GOP is already too compromised to recover from anti-electionism even if Trump is defeated in 2024. Perhaps the GOP is caught in an irresistible downward spiral of conspiracy theories and ruthless power-grabbing. I hope that isn’t true, and I hope we see it proved untrue—but even if it is true, I would argue that this would make it all the more necessary to defeat the GOP at every turn in the hope of something better eventually taking its place.

Certainly giving up on the hope of return to normal democracy—accepting a “new normal” of election denialism and election-thwarting, potentially even spreading to both parties—cannot be a price we are willing to pay to try to get things done (or to try to prevent things from getting done). No matter how grave the policy considerations, sabotaging democracy and relying on the greater ruthlessness of one party to seize power can only be what the protagonist of one of my favorite movies called “a short route to chaos.” You can’t keep playing chess with people who for whom cheating is a major component of their play.

I don’t believe a world with more than one major party that is committed to functional elections is too much to hope for. In 2024, defeating Trump is a more plausible bid for a world with a post-Trumpian GOP, a post-Trumpian world, than any other voting choice in relation to any other likely better world.

See also Reflections on voting as a pro-lifer: Preamble to a Trump polemic

Thank you for this article. I can appreciate what you said about Trump. I did vote for him twice. However, you bringing up all the shenanigans he did running last time in 2020 and his divisive and inflammatory language as president from day 1. In addition to his ramblings and irrational tweets, he made throughout his presidency, really made me sick to my stomach and it's why I'm angry at the Republicans for putting us in this position. However, Harris is such a bad candidate, her incompetence and her lack of knowledge of just basic things is disheartening on a whole other level of danger to our country and the common good. On top of her horrible position on abortion which is the only issue she has a clear stance on (other than hating Trump).

My vote doesn't count very much living in the state of California., where the results in this state are a given for Harris, so i'm not sure if i'm even going to bother voting for a president this time around. I'm thinking I'll just focusing on Senate and local races.

The USCCB stated abortion and euthanasia are pre-eminent threats “because they directly attack life itself, the most fundamental good and condition for all others”; Cardinal Ratzinger countered “proportionate reasons.” Would you agree that such a threat/reason is only proportionate, if it a. attacks life itself, or b. is a more fundamental good? My friends who vote Democrat roughly use a., citing closed borders, for example, as an attack on life proportionate to abortion. Are you arguing b.: that a vote against Trump is necessary to preserve a two-party system, a good upon which the right to life depends?