Password insanity: my personal approach revealed

[how I generate and remember unique passwords for every system I log into]

Passwords are hardly the vanguard of online security that they once were, what with biometrics, smartphone credentialing, and other approaches. Still, they aren’t going away any time soon. There are a few major approaches to passwords:1

First, of course, is the noob default: Use something simple and repeat it everywhere (password1; your significant other’s birthday; your kids’ names; etc.). This is a dumb approach, but lots of people still do it!2

For those who want to level up a bit, one option is creating an easy-to-remember formula: for example, starting with boilerplate stock elements reused each time, but mixing in select characters from the name of the website.3 This is an okay, easy-to-remember approach that I’ve used in the past.

There’s the xkcd approach widely known as “correct horse battery staple,” which has been criticized for using common words, not to mention how do you associate each random word string with the right account?! This one was not well thought through. (We expect better, xkcd!)

Many seriously security-minded people use unmemorizably complex passwords and keep track of them all with a password tracking application. This is a fine approach—unless the password tracking app is compromised!

And then there’s the insane thing I do … which may not work for anyone but me!

I have no fear publicly revealing my password generation method, which I use to generate unique, fairly unbreakably complex passwords for every system I log into. That’s because my method is utterly dependent on the user’s mental landscape; your mental landscape is different from mine, and the mental paths you would follow—if you can use my method at all!—will be nothing like mine. Even if you know me pretty well, there is essentially zero chance that you will be able to reconstruct any of my passwords, or even get on the right track.

To use my method, you need a somewhat literary mind and a good head for quotes and phrases. You also have to have fixed landmarks in your mental landscape that you can reliably return to again and again. The trick is finding the right landmark for each account.

Yahoo

Here’s an example for an account I don’t have: a Yahoo account. Yahoo. What does Yahoo make me think of? What’s my landmark?

Easy peasy. Yahoo immediately makes me think of the 2000 time-bending thriller Frequency.4 Yahoo will always make me think of Frequency; it is a fixed landmark in my mind. (You can’t rely on ephemeral assocations based on something that happened to you yesterday or last week; it has to be a fixture in your mind.) That’s not necessarily a great example, because Yahoo will make a lot of people think of Frequency, and I like to rely on more personal assocations. Still, for the purposes of this demonstration, that might be all the better.

The next step is picking a movie quote from Frequency that I can also reliably return to again and again—with caveats. The quote has to be the right length; it should involve unusual words; it should be an obscure quote; and ideally it will be linked in the dialogue to Yahoo.

Perhaps the first movie quote from Frequency I think of is “I’m still here Chief.”5 This is too short, too obvious, made of common words, and, crucially, not linked in the dialogue to Yahoo. I know that even if I forget my password and I’m trying to retrack my footsteps, I’ll reject this one every time.

“It’s a magic word, like abracadabra”6 is longer, and “abracadabra” is an unusual word. But that’s not the exact quotation, and that could trip me up when I’m trying to retrack my steps. (The exact quotation is “It’s a magic word. It’s like … like abracadabra, but even better.” Meh.)

Hey, you know what works? “Shoulda, woulda, coulda, pal.”7 That’s pretty solid, and I know I can zero in on it every time, within seconds.

Then I just append a stock numeric/special character prefix or suffix that I use to complicate all my passwords, and I’m done. So my Yahoo password might be something like shouldawouldacouldaPal$98 (capitalizing the P in “pal” as the outstanding word in the quote).

Not necessarily a great example, but I promise my associations for Google, Facebook, and AT&T are far more obscure and personal to me!8

This approach always works for me,9 and I never forget a password10—or, if I do forget them, I can always recreate them by following the same mental pathways.11

Tumblr

Let’s try another one for another a site I don’t use: Tumblr.

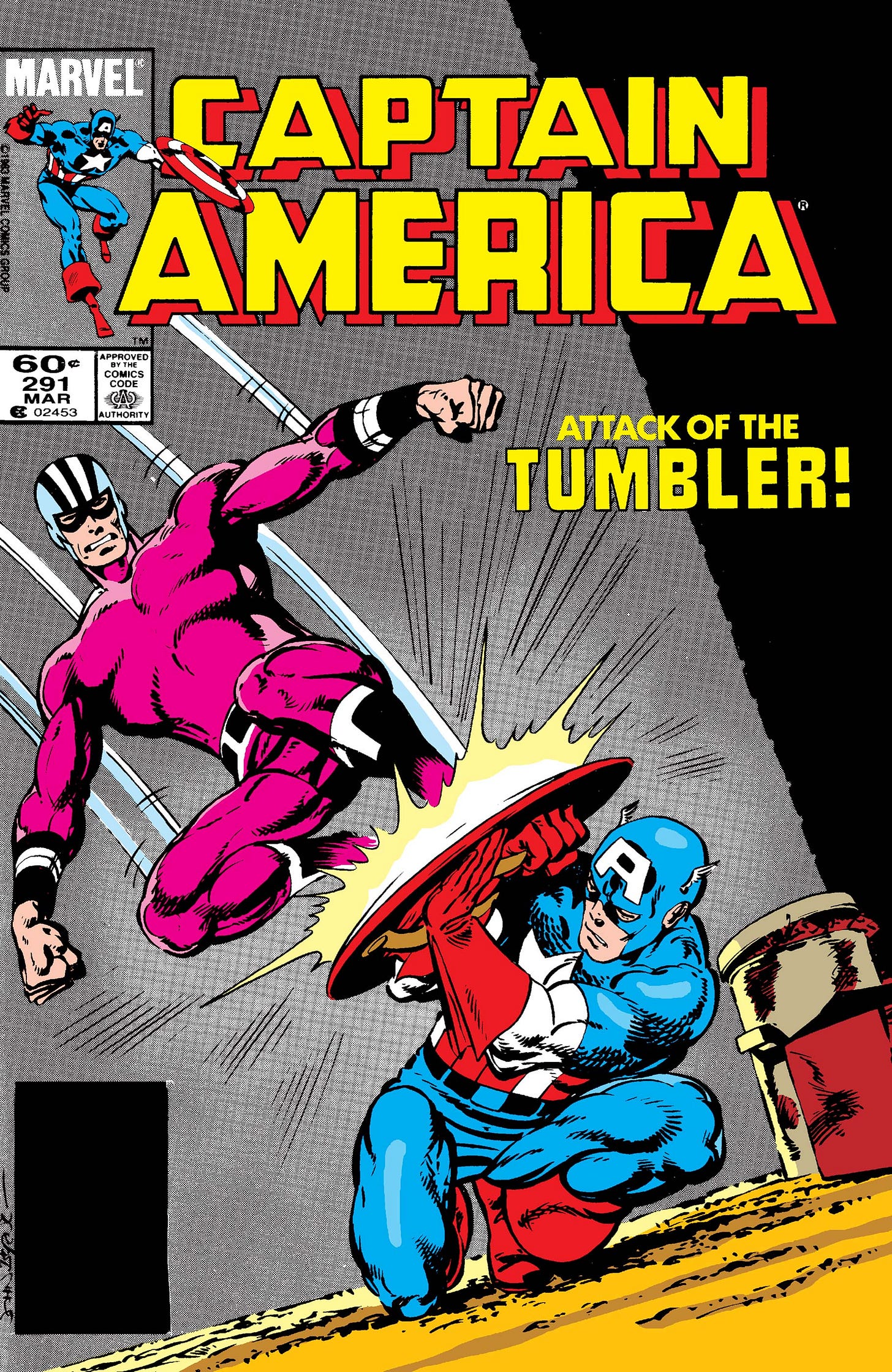

First, I quickly and easily reject the Tumbler-Batmobile in Batman Begins (ohyouwouldntbeinterestedinThat$98).12 Way too obvious!

The Tumbler villain in Marvel Comics is far more obscure, but still not personal enough—and anyway I can’t think of any interesting quotes in connection with that character. I love a good comics quote, but this character got no lines that stand out to me.

What else is a tumbler? A drinking vessel, of course—but also, and better, a component in pin tumbler locks. That makes me think of scenes in movies or comic books where characters pick locks by somehow sensing, hearing or feeling the tumblers.

And now I know my quote, one I can come up with every single time, in seconds: BlindPeteusedtodothisallbytouch$98 (Silverado).13 That’s a good one! Almost makes me wish I had a Tumblr account.

Banks

Let’s play a game!

I’ll give you three imaginary passwords to real banks based on my method.

I’ll explain the first two passwords.

For the third bank, I won’t ask you to generate my password—that would be too tricky. Instead, I’ll give you the third password. All you have to do is tell me what the password means and why!

Ready? Let’s play!

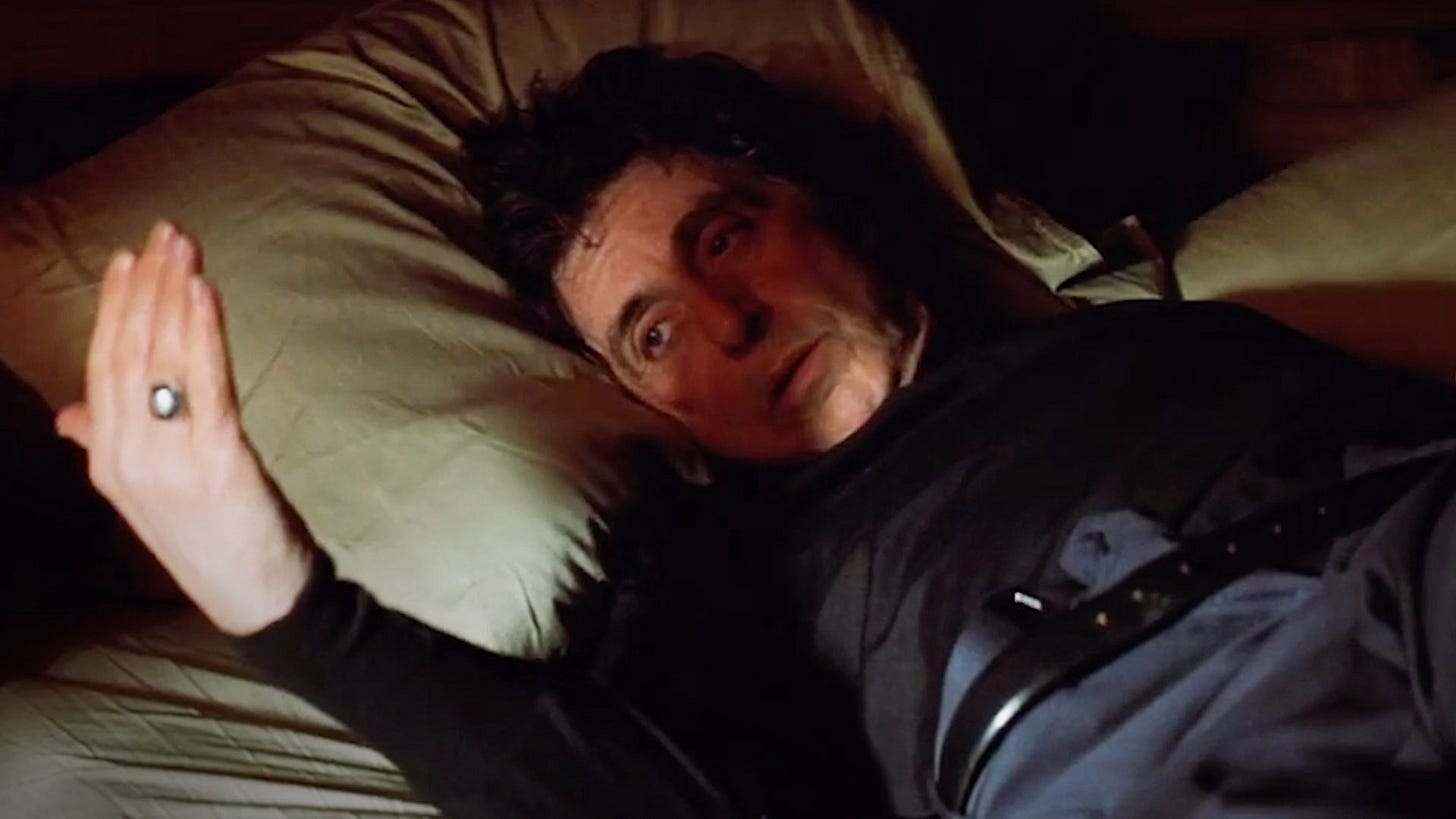

Bank 1: Citibank. First I think of the bank slogan: “The Citi Never Sleeps.” Never sleeping makes me think of insomnia, which of course makes me think of the 2002 film Insomnia.14 Then I think of the outstanding quotation in that movie connected to the idea of not sleeping: “A good cop can’t sleep because he’s missing a piece of the puzzle. And a bad cop can’t sleep because his conscience won’t let him.” That’s way too long even for an initialization, but I’ll take the initialization for the first half: Agccsbhmapotp$98. Initializations are great if you can come up with a long enough quotation!

Bank 2: Capital One. What’s their slogan? “What’s In Your Wallet?” What does that make us think of? Come on, Tolkien fans, obviously The Hobbit’s “Riddles in the Dark”: “What has it got in its pocketses?” And so the answer, which is too short to initialize this time, is HandsesKnifeStringornothing$98.15 This is outstanding, partly because “handses” isn’t a standard word, and because Gollum’s responses are scattered amid narration and Bilbo’s responses, and it isn’t a direct quotation from the book, but I can still recreate it every time.

What fun!

Okay, challenge round! Bank 3: JPMorgan-Chase. The slogan I’m going with is “Chase: What Matters Most.” What matters most? To make it sporting, I’ll pick a password based on an association that is not super personal: an initialization that is potentially decipherable by anyone with enough of cultural overlap with me, who can guess what “what matters most” might suggest to someone like me: SyftkoGahraattwbauy$98. You tell me what it means! If you want a hint, there are two in the last footnote.16

Does anyone else do anything like this?! What do you do (in general terms, of course, if you can mention it without compromising your accounts)?

Note: Whichever of these approaches you use, you should also use 2FA wherever possible.

A friend of mine who works in computer security says he would rather you use “password” as your password with 2FA than an unbreakably complex password that you change every 30 days without 2FA. See note 1.

For example, let’s say that you happen to love the 1969 Amazin’ Mets. (Why would I pick this example? See note 4.) Your password stock boilerplate might be amaZmet + 69# (capitalizing the Z just to be tricky). Now let’s say you’re creating a Substack password. Your formula might be to take the first six letters of the site name (Substack) and drop the third letter: su/sta. So your Substack password would be amaZmetsusta69#. Your Amazon password would be amaZmetamzon69#. Etc. Not super unbreakable, but easy for you to remember, and at least moderately difficult to crack. (See note 1 above!)

Early in Frequency, which is set in 1999, Noah Emmerich, playing the best friend of Jim Caviezel’s protagonist, laments having lacked the foresight to buy stock in Yahoo. Later, Caviezel has an opportunity to send a message back in time to his best friend as a child in 1969—resulting in a new timeline in which Emmerich pulls up in a Porsche with a vanity tag reading YAHOO 1. (The 1969 Mets figure prominently in Frequency. See note 3.)

“I’m still here Chief” is the message that Caviezel’s father Dennis Quaid in 1969 sends to his son in 1999, etching it with a soldering iron on the desk they share across time.

The message that Caviezel sends back in time to his best friend is that he (Caviezel) is Santa Claus and he’s going to give him the biggest Christmas present he’s ever gotten: a word he must remember for a long time. The word, of course, is “Yahoo,” and Caviezel tells him it’s “a magic word … like abracadabra, but even better.”

“Shoulda, woulda, coulda, pal” is Caviezel’s response to Emmerich’s initial lament about not buying Yahoo stock.

I don’t use my Twitter/X account any more, but I’m still proud of the associated quotation. Close family members might be able to guess the movie, but even they would struggle to find the exact quotation.

Almost always. I occasionally run into a brick wall where I can’t make an association, but this is rare.

I have been known to occasionally forget a password. Very occasionally. On occasion.

Almost always. I have rarely been known to outsmart myself and been obliged to go through some password recovery method. Even then, it has sometimes happened that, when I go to create the new password, the extra effort of trying to create a “new” password allows me to stumble upon my original password!

“Oh, you wouldn’t be interested in that” is Morgan Freeman’s smirking response to Christian Bale’s Bruce Wayne at the latter’s query about the Wayne Enterprises military prototype vehicle that becomes the Batmobile—after it’s been painted black, naturally.

Kevin Costner’s character says this as he picks the lock on the jail cell in Turley shortly before their prison escape.

I have never seen the 1997 Norwegian original.

The question is not a proper riddle, so Bilbo lets Gollum have three guesses, and Gollum slips in a fourth guess at the end. “Handses!” is almost right, but Bilbo took his hands out of his pocket just in time. “Knife!” could have been right, but Bilbo happened to have lost his. “String, or nothing!” was a pure shot in the dark. The actual answer, which Gollum almost might have been expected to guess correctly, was the magic ring.

Clue 1: It’s a Christian thing, and …

Clue 2: … it helps to be old enough to have some familiarity with the King James Version—or, as reader

points out in the comments, to have a background in church choir singing.

I think the XKCD approach is okay if done properly. The linked article assumes that users are thinking up with the words themselves, which is a terrible idea. (First rule of security: you do NOT have a good RNG in your brain.) If the words are *properly* randomly chosen from a list of 10,000 common words, using a computer or something like diceware (in which you roll physical dice to choose a word from a premade numerical list), there are 10^16 possibilities, roughly equal to a 9-character alphanumeric string, such as Gg6sPTrBb. This isn't *great* (I prefer at least 20 characters), but it's still better than Tr0ub4dor&3, let alone password123.

You can improve on this further with a larger word list. For one site, choosing random words from the entire online OED, I used to have a password consisting of a technical legal term followed by three dialectical words that I've never heard in real life. (My account on that site is long since deleted, but it still seems like a good idea not to say exactly what the words were. You'll have to take my word for it that it sounded funny.)

2FA has pitfalls that should be mentioned. For one thing, SMS (text messaging) is NOT secure; it can be intercepted relatively easily via SIM hijacking. A real 2FA app (e.g. Google Authenticator) is better, but my bank, for example, only allows 2FA via SMS and voice calls. That's security theater.

For another thing, there's a real tradeoff between security and accessibility. Phones get lost, or stolen, or broken, or have dead batteries, or don't have service in a particular area, etc. To require 2FA is to allow the possibility that you won't be able to get into your account in some unusual circumstance when you really need to. IMO, this tradeoff should be discussed honestly, and it shouldn't be assumed that everyone has a working phone on them at all times.

As for the system described here, it's impressive, but sounds to me like an insane amount of mental effort, to the degree that the nuisance of creating a new password would discourage me from signing up for any new sites. Personally, I'm very happy with Bitwarden, which, like all reputable password managers, uses end-to-end zero-knowledge encryption, meaning that if even if an attacker was able to exfiltrate data from Bitwarden's servers, they'd be unable to read any of it. Bitwarden does require 2FA when accessed from an unrecognized device, but allows email to be used as the second factor. This means that memorizing two passwords, one for Bitwarden and one for email, allows me to log in without my phone if need be.

I built a custom “module” approach that essentially hybridizes 3 (the XKCD approach) with 2 = building out a “security alphabet” of 26+ unique words that I can quickly associate with each letter of the alphabet, then string those words together (e.g. for CVS, spell out CabbageVacationSushi) and THEN tack on some slightly more default characters and numbers, etc.