More than 35 years ago, as a cartooning student at the School of Visual Arts, I created a number of small-press comic books for a cartooning class co-taught by Will Eisner (best known for the Spirit and A Contract With God) and André LeBlanc (a longtime Eisner assistant also known for his work on the 1979 graphic novel The Picture Bible). Having made a thing here at Dailies & Sundays of commenting on and critiquing the work of others, it’s only fair that I present my own work for scrutiny!

For Easter Week, then, here is an Easter-themed comic I did in college in 1989.

Since my small-press comics were reproduced via photocopier and assembled by hand, the original presentation was black and white.1 In those days, when I did work in color, I typically used Japanese colored pencils that I got from a classmate. About a decade later, for my freelance cartooning work I started using markers, with corrections and special effects done in Photoshop: the approach I took here.2

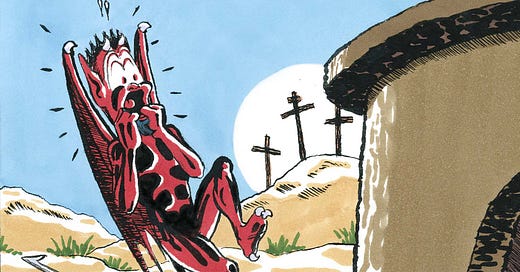

The theme of this comic, of course, is the defeat of death in the resurrection of Jesus—the conceit being Death personified as a battered, tattered Grim Reaper with his scythe cracked over his skull. This is naturally a terrible shock to Satan: seeing his virtually invincible right-hand man utterly defeated by Christus Victor, Christ the victorious champion.3

The theme of the triumph of good over evil was a recurring motif in my work at this time. At the time I was very proud of the conceit of this comic, and I still like the idea, though my feelings about it are today are a bit more complicated.

Let’s start with technique. To start with, I’m pleased to see that I got the most important call right: As so often, the most important creative choice was getting the correct “read,” with the panel elements arranged correctly from left to right. Here I made the right choice. The Devil is on the left, so we get his extreme, full-body reaction before we register what he’s reacting to—always a good dynamic in humor!—i.e., the figure of Death pummeled almost to a Beetle Bailey–like pulp, which is also funny, and adds to the humor of the Devil’s stricken reaction. It would have been easy, but mistaken, to arrange it the opposite way.

Of the two key figures, Satan is the more successful, I think. There’s some clear superhero comics influence in the torso and limbs,4 but with a highly cartoony level of exaggeration in the expression as well as the body language (clearly reflective of the massive influence on my work of Calvin & Hobbes’s Bill Watterson, with a little Tex Avery5 thrown in). I like the emanata around the Devil’s head (the bursty lines showing how freaked out he is), but the literal flying sweat beads6 are a clumsy over-complication: I should have stuck with one or the other, not both.

The Devil’s dropped pitchfork with its shadow helps to define the space around the figure, and—along with his tail twitching behind the sepulcher—establishes just how high he’s jumping. (On the other hand, the pitchfork tine “touching” the panel border is a mistake. It should either be clear of the panel border or clearly go behind it—or perhaps protrude into the hypothetical gutter space beyond the border.)

I worked hard on the figure of the Reaper, but I now think the end result is cluttered and hard to read. (Especially in the black-and-white original; the coloring definitely helps here!) I like the way the cloth drapes over the pelvis, but we really didn’t need to see the back of the rib cage showing under the left front side of the rib cage. The emanata around Death’s head (stars, a ringed planet, etc.7), indicating how stunned he is, are not well executed and partly lost against the boulder. At least most of the rest of the panel is clean, so it kind of resolves without too much trouble. I like how Death has a black eye and crisscrossed bandages on his skull!

Beyond the figure work, the rest of the composition, unfortunately, isn’t well thought out. Above all, it’s dominated by a single weird choice that now seems inexplicable to me. One of the most interesting and humbling things, to me, about revisiting my youthful creative endeavors (writing as well as drawing) is how little aware I was of the influences and inspirations that (obviously, I now see) shaped my work. In this case the first thing that jumps out at me is “Why on earth did I draw the sepulcher that way, with a slab for a roof and so forth?” And the answer, I’m afraid, is “Clearly my primary (subconscious!) influence in that regard—and I didn’t even use it as well as I could have—was the cartoon Stone-Age architecture of The Flintstones.”8

The stone used to seal the tomb, likewise, is simply a giant boulder rather than the disk-shaped stone usually pictured.9 As Watterson once ruefully remarked regarding an early tyrannosaur strip, “Obviously, I did no research whatsoever.”10

A few other quick notes:

The little kibitzer character on the lower left11 is named Orville. He is overtly (though again unconsciously!) reminescent of editorial cartoonist Pat Oliphant’s penguin Punk.12

My ink brushwork is okay as far as it goes. The hatching work (the textured penstrokes used to create shadow effects) is beginner’s work with little understanding. (I did better in some later cartoons I’ll share at some point.)

In keeping with John 20:5–7, you can see Jesus’ grave clothes on the burial bench in the sepulcher. (Naturally the bench also is topped by a stone slab, because why wouldn’t it be.)

Oh, and of course the banner caption at the top should read “A.D. 33,” not “33 A.D.”! (I didn’t know this in 1989. I think today I would make it “Easter morning, A.D. 33.”)

Narratively, the conceit implies a prior event involving Jesus, in the act of rising from the dead, not only smashing the Reaper’s scythe over his head but also beating him to a fare-thee-well! The image of Jesus as a heroic warrior is an old one,13 and as congenial to Evangelical imagination in the 1980s14 as it is today. Death in Christian theology is of course an evil (“the last enemy,” in St. Paul’s phrase) and only a personification, but I’m still less comfortable with ascribing even metaphorical cartoon violence to Jesus than I once was.

Anyway. Despite its issues, I still like this cartoon and I’m still proud of it!

See more SDG art >

Below is the black and white original version. In coloring the image, I took the liberty of creating textures and lighting effects on the ground and the sepulcher as well as enhancing the texture of the stone. I also created a sunrise centering the crosses on the horizon. I now think it’s odd that in the original I put some grass at the base of the sepulchur but nowhere else, so I expanded on this in the color version. The little dust clouds under Satan’s heels are now a bit lost in the background grass, but I think it’s okay.

For this effort, I dug up my original, hand-inked artwork and had it scanned and printed; the coloring was done on a print. Historically I’ve found that standard-weight photocopy paper works better than higher-quality paper, because the marker bleed tends to create the smoothest look. In the past I’ve used alcohol-based Prismacolor markers, but very unhappily these have been discontinued. I bought some Japanese markers for this effort. I’m not entirely happy with them; it seems to me they don’t blend as well as my old Prismacolors, and I needed to smooth out the colors in Photoshop. I still like the textured look of marker work better than pure digital color.

For the heck of it, here’s the reverse side of the hand-colored original for this cartoon. You can see that the blending issues in the sky and especially the ground. With the sepulcher I was able to work quickly and smoothly enough to minimize this issue.

I was not yet Catholic in 1989 and not super familiar with various forms of atonement theory, so I might not have known the phrase Christus Victor—but it was a big idea in my thought nevertheless.

For some reason flying sweat beads are called plewds, a name popularized by Beetle Bailey cartoonist Mort Walker’s short 1980 book The Lexicon of Comicana. (Walker also popularized the general term emanata.)

Flintstones style architecture is, alas, more visually interesting than my sepulcher! The curved sides give the house below an appearance of being carved out of a boulder, whereas the resolutely straight vertical line outlining the exterior of the sepulcher makes it look like troweled concrete. The uneven lines of the Flintstones’ slab roof are more interesting than whatever the sepulcher roof is supposed to be. Not only did I do no research, I clearly put no thought whatsoever into it!

To say nothing of the square, cork-like sealing stones more common in Jesus’ day. Again, I didn’t even look at artwork common at the time.

In particular, Watterson faulted his early T-rex effort for the number of fingers, the alligator belly, and the dragging tail—“all wrong,” he wrote. Not entirely unlike my Flintstones sepulcher, Watterson was probably working from half-remembered illustrations and plastic models from his boyhood when we imagined T-rexes walking like Godzilla. (This was six years before Jurassic Park.)

This kind of character is an editorial cartooning convention called a dingbat. (This one doesn’t come from Walker’s book, but from cartoonist and cartooning theorist R. C. Harvey.)

See for example the warrior Christ in the early medieval poem The Dream of the Rood.

I was never a fan of Christian pop star Carman or his signature spoken-word song The Champion, which imagines redemption as a cosmic boxing match between Jesus and the Devil—but the sensibility behind the song was ubiquitous in my religious background culture.

I saw this comic and thought "Have I seen this gag before somewhere? Did Jesus beat up Death in an early 'Casey and Andy' strip?" So I looked it up, and boy was my memory wrong. :-D

https://galactanet.com/comic/view.php?strip=12

Many years ago I had a visual dictionary. It had a section on cartooning which featured a two-page spread single-panel cartoon with examples of all those conventional cartoon symbols along with labels for them -- done by Mort Walker. I had concluded that Walker made the whole thing up as a gag just for that dictionary because I had never seen those label-words ("plewds", "emanata", etc.) used or defined anywhere else until today.