1. What is racism? Forming a Catholic perspective

[First in a series, not just for Catholics, but perhaps of particular interest to Catholics and other Christians]

People have been asking me lately if I’ve seen Am I Racist?, the new movie featuring Catholic pundit and provocateur Matt Walsh (I haven’t), or if I plan to see it (probably not; certainly not anytime soon). Right now even movies I want to see are falling by the wayside due to my teaching commitments—and frankly what little exposure I’ve had to Walsh has been more than enough to motivate me to try to avoid him.

At the same time, for various reasons, race and racism have been topics of renewed discussion and public attention in recent months. I’m no expert in this area, but for many years I’ve tried to learn what I could from people with experiences and expertise different from mine, significantly including Black Catholic scholars, clergy, public speakers, and ordinary Massgoers.1 I’ve sought to do this within the framework of the Catholic intellectual tradition, relating what I’ve learned to Catholic social teaching and Catholic anthropology (areas in which, as a Catholic deacon with a couple of seminary degrees, I do have a certain competence). Along the way, I’ve worked on compiling an account of what I think I’ve learned—an account I think I’m now ready to start to share, in serial form and still very much a work in progress. (The title phrase “forming a Catholic perspective” is meant to suggest this sense of ongoing effort in dialogue with other perspectives.)

For what it’s worth, I think the Walsh movie title asks the wrong question. The question in the first place is not “Am I racist?” but “What is racism?”—and this entails a range of other questions:

Is racism simple or complex? One thing or many?

Where does it come from? What are its roots? How is it perpetuated?

Is racism a perennial human problem or a product of particular historical and cultural circumstances? How is it related to other forms of bias, prejudice, or bigotry?

How do we recognize racism? What does resistance look like? What does complicity look like?

It’s easy to assume we know the answers to questions like these, but common ideas on this subject can be misleading and derail conversations before they get started.

One thing I’ve learned is that it’s important to be aware that how we perceive such matters varies considerably with our experiences, background, interests, and blind spots. For example, my perspective is shaped by my experiences as a White American Catholic deacon who has lived most of his life in northern New Jersey. As it happens, I have served for many years in (and attended for decades) a parish in a poor Newark-area neighborhood with a diverse population of parishioners, including a large Hispanic community, Africans and African-Americans, Filipinos, and others. (Since Haitian immigrants have been in the news, I’ll mention that we once had a sizable Haitian community, with Masses in Creole, though they’ve since migrated to another parish.) I think I’ve learned quite a bit from these and other experiences. Still, I recognize that nothing I’ve learned gives me much insight into the experiences of, say, a Korean-American Pentecostal living in Texas, an Inuit Catholic in northern Quebec, a Siddi Muslim (of African descent) in Pakistan, or a Tibetan Buddhist in China.

My reading, learning, and thinking about this topic has naturally focused on the forms of racism that are most familiar to me. In these writings, then, I will focus mainly on racism in a Western and especially American historical and cultural context. In particular I will write about the role of slavery in European and American history, the American legacy of White supremacy and anti-Black racism, and the part played by the Catholic Church in this history. This is not meant to imply that racism is uniquely Western or Christian or vice versa, or that racism in America is worse than in all other countries. Nor is it to minimize racism or bigotry against other minorities. I’m just trying to write what I know, relatively speaking, and not what I don’t.

The problem starts with disagreeing about where the problem starts

If there’s anything virtually all Americans agree on regarding racism, at least in theory, it’s that racism (whatever it is) is a very bad thing. If there’s anything else that most Americans are sure of, it’s probably that they personally are not culpable in it! (This is part of the problem with the title of the Walsh film: The very words “racism” and “racist” have become so odious that labeling a person, or even a remark or action, as “racist” can be perceived as more offensive and more taboo than doing or saying actually racist things. Even literal neo-Nazis and KKK members often deny being “racist,” to say nothing of those whose racial attitudes or blind spots are more subtle.)

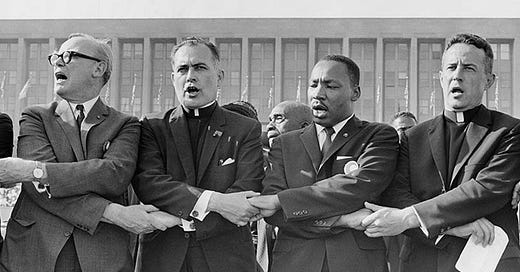

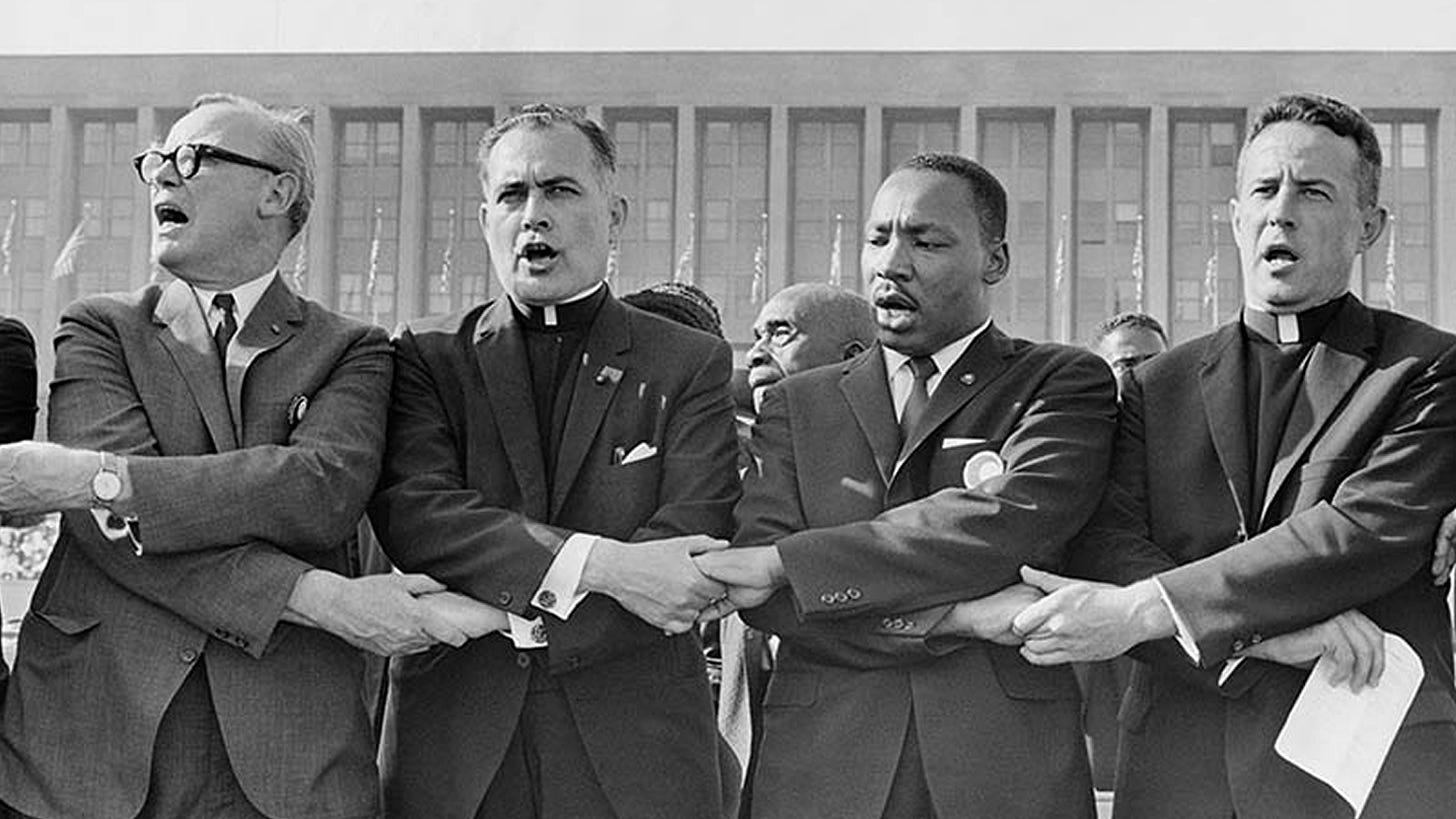

How big a problem is racism today in American society generally and in US churches in particular, including Catholic churches? What role should churches play in opposing racism? Perceptions among Americans, including American Catholics, differ sharply between people of color, particularly Black Americans, and the White majority. Notwithstanding churches like mine, Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous remark about 11 o’clock on Sunday morning being the most segregated hour in America still holds substantially true today, and this has implications for the relationship of US churches to issues of race.

The first time I addressed this topic as a deacon in a significant way was the year after my 2016 ordination, in the wake of the 2017 Unite the Right neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the violence that left one White counter-protester dead (and led to years of controversy over President Donald Trump’s infamous “very fine people” comment). The readings that Sunday happened to be united by a running theme of the universality of grace and charity, implicitly invoking the unity of the human race. On social media I suggested that homilists seize this opportunity to address the topic of racism in the light of the gospel (a suggestion I wasn’t alone in making).

In my homily that Sunday, I tried, as I always do, to bring together the teaching of scripture and of Church authorities in relation to the pressing circumstances of the moment without injecting my own opinions. Among other things, I quoted from a 1979 pastoral letter on racism, Brothers and Sisters to Us, from the U.S. Catholic bishops:

Racism is not merely one sin among many; it is a radical evil that divides the human family and denies the new creation of a redeemed world. To struggle against it demands an equally radical transformation, in our own minds and hearts as well as in the structure of our society.

The letter also describes, I noted, how the enduring legacy of racism

permeates our society’s structures and resides in the hearts of many among the majority. Because it is less blatant, this subtle form of racism is in some respects even more dangerous—harder to combat and easier to ignore.

I pointed out that the bishops acknowledged, with striking self-critical harshness, their own historical failures to address the “radical evil” of racism in timely and appropriate ways:

How great, therefore, is that sin of racism which weakens the Church's witness as the universal sign of unity among all peoples! How great the scandal given by racist Catholics who make the Body of Christ, the Church, a sign of racial oppression! Yet all too often the Church in our country has been for many a “white Church,” a racist institution.

Responses to this homily (and subsequent ones similar in theme) were mixed in ways that were unusual, yet not unpredictable. I got pushback, complaints, and even critical emails, all from church members with skin tones in one range—and approving nods, smiles, and handshakes, all from parishioners with skin tones in another range. All ostensibly brothers and sisters in Christ, sitting side by side in the pews; all receiving the precious Body and Blood of the Lord during Communion: yet experiencing the world in significantly different ways based in large part on their skin color.

In June 2020 a Pew study found that while a majority of Black Christians consider it important to hear topics like racism discussed from the pulpit, a majority of White Christians either consider it unimportant or think it shouldn’t be done at all. Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) founder and CEO Robert P. Jones has found that White Christians are consistently more likely than their nonreligious neighbors to be skeptical and dismissive of the role of racism in ongoing social problems. For example, a 2018 PRRI poll found that White Christians, including White Catholics, were nearly twice as likely as religiously unaffiliated White people to view the killings of Black men by police as isolated incidents rather than part of a pattern of how Black men are treated by police. As you can imagine, these differences in perspectives and priorities can be demoralizing and alienating for African-American Christians who may face more resistance on the subject of racism from fellow Christians who are White than their unchurched White neighbors!

Notes from Catholic teaching

Racism or bigotry of the most overt and explicit kind is relatively easy to recognize and condemn. In principle, if someone comes right out and directly claims that White people are genetically superior to minority racial groups, or advocates policies explicitly discriminating against minorities, most Americans would agree that such views are abhorrent. Likewise, if someone is hostile or demeaning toward a given demographic explicitly because of their skin color, this would, in principle, be widely recognized as bigoted and undesirable behavior.

But racism in its various manifestations and effects is far more complex and pervasive than these relatively rare behaviors. For Catholics, it’s worth noting that the last three popes have all urged that racism be taken seriously as an persistent and insidious danger—one more versatile and harder to eradicate than might be supposed. In 1999, during a pastoral visit to the United States, Pope St. John Paul II declared (emphasis added):

As the new millennium approaches, there remains another great challenge facing … the whole country: to put an end to every form of racism, a plague which your Bishops have called one of the most persistent and destructive evils of the nation.

In 2008 Pope Benedict XVI warned about “disturbing new forms of racism … being manifested in various countries.” And in 2020 Pope Francis wrote in his encyclical Frateli Tutti (“All Brothers”):

Racism is a virus that quickly mutates and, instead of disappearing, goes into hiding, and lurks in waiting.… [Racism] retreats underground only to keep reemerging. Instances of racism continue to shame us, for they show that our supposed social progress is not as real or definitive as we think.

In 2018 the USCCB released an updated pastoral letter on racism, Open Wide Your Hearts: The Enduring Call to Love. This letter comments on how racism can go undetected and unrecognized in those whom it affects:

Racism can often be found in our hearts—in many cases placed there unwillingly or unknowingly by our upbringing and culture. As such, it can lead to thoughts and actions that we do not even see as racist, but nonetheless flow from the same prejudicial root. Consciously or subconsciously, this attitude of superiority can be seen in how certain groups of people are vilified, called criminals, or are perceived as being unable to contribute to society, even unworthy of its benefits.

The letter also addresses the complex and much-misunderstood reality sometimes called systemic, institutional, or structural racism (emphasis added):

Racism can also be institutional, when practices or traditions are upheld that treat certain groups of people unjustly. The cumulative effects of personal sins of racism have led to social structures of injustice and violence that makes us all accomplices in racism.

This passage footnotes a passage in the Catechism of the Catholic Church which addresses the general topic of “structures of sin” or “social sin,” of which systemic racism would be a particular example (emphasis added):

Thus sin makes men accomplices of one another and causes concupiscence, violence, and injustice to reign among them. Sins give rise to social situations and institutions that are contrary to the divine goodness. “Structures of sin” are the expression and effect of personal sins. They lead their victims to do evil in their turn. In an analogous sense, they constitute a “social sin.” (Catechism of the Catholic Church #1869)

How does this work in practice? What are “structures of sin” or “social sin” in concrete terms? What do they look like? How do personal sins—for example, racist acts—contribute to such structures? Where does racism come from in the first place? Is it innate? Is it learned? How is it like other forms of bias or prejudice? How is it different?

Starting principles

Historians and sociologists continue to debate the origins of the concepts of race and racism, and whether some forms of ancient or medieval forms of bias and bigotry can be classified as racism or perhaps “proto-racism.” (In a similar way, scholars may distinguish more or less sharply between modern racialized antisemitism and medieval anti-Jewish bigotry—a topic I will revisit.) I have no intention of delving into such scholarly questions. For simplicity’s sake, I will use “racism” to mean something like “racism as we know it in a modern Western cultural context,” and in other contexts limit myself to terms like bias, bigotry, prejudice, ethnocentrism, and so forth.

Whatever conclusions anyone may reach about the history of the concepts of race and racism and how such terms should be defined, in general my thoughts in this area are grounded in two fundamental premises:

Unjust forms of bias, including ethnocentrism and prejudice, are perennial human failings deeply rooted in human nature. Active resistance to bias of these types is thus a perennial moral necessity. (More about this below.)

Racism (as we know it in a modern Western cultural context) is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon with roots both in perennial human dispositions and in a tangle of historical and cultural factors. Such factors include Western expansionism in the Age of Exploration and beyond; the scientific revolution; Africanized chattel slavery and the modern slave trade; and the enduring cultural, legal, and institutional structures originally developed to support and legitimize this form of slavery. Resistance to racism in this sense must reckon with these historical and cultural factors and their ongoing effects in our world. (More about this to come.)

Love, bias, and socialization

“No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin,” Nelson Mandela famously said, “or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.”

This is an uplifting sentiment, but Mandela’s glass-half-full positivity may tacitly acknowledge a more complex reality. Note that Mandela speaks of learning to hate, but being taught to love. The distinction matters, since, while it may be true that love “comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite,” it is also true that those who are not actively taught to love and esteem equally—intentionally socialized to value equally those who are different in various ways—can easily learn, by default, to hold in lower esteem those who are different, and to fall into prejudicial, discriminatory ways of thinking and acting.

Biased attitudes toward other groups are not inborn, but they are perennial and ubiquitous, found throughout history and all over the world. Quite apart from questions of historical inequities or systemic injustice, simply as a matter of constant human nature, the struggle against unjust attitudes and behavior toward other groups can never be won once and for all. For a glass-half-empty counterpoint to Mandela’s statement, we may think of the wry observation, credited in different forms to Hannah Arendt and Thomas Sowell, that civilized society is in every generation invaded by barbarians—otherwise known, of course, as children—and the work of civilizing the barbarians is never-ending.

The preference of many parents (particularly though not exclusively White parents) for “colorblind” parenting—rooted partially in the wishful idea that children are naturally egalitarians who simply won’t see or think about race or other differences or form prejudicial attitudes if they aren’t led astray by bad example—is misguided. Bias itself is not innate, but the tendency toward bias is, and its seeds begin to manifest strikingly early.

Preferring the familiar

Even before birth, babies manifest an innate tendency to prefer the familiar to the unfamiliar: for example, their mother’s voice to strange voices, and even the sound patterns of their mother’s language to that of unfamiliar languages. Children who are loved naturally love in return, though they also quickly begin not only to prefer familiar people and situations, but to manifest stress responses like anxiety and fear in the presence of the unfamiliar. (Stranger anxiety typically intensifies around six to eight months old.)

Babies begin to categorize people by factors like complexion, and to form preferences for familiar traits. A number of convergent studies have found that infants as young as three months prefer looking at faces from their own racial or ethnic group (that is, people who resemble the family members they see every day) to faces of other racial or ethnic groups.

This tendency to prefer the familiar and to distrust or fear the unfamiliar is natural and (within limits) healthy. Still, it easily gives rise to spontaneous forms of biased attitudes. C.S. Lewis in The Screwtape Letters notes how children easily assume that whatever is familiar to them is normative and whatever is not is somehow abnormal—how a child might feel, for example, that “the kind of fish-knives used in her father’s house were the proper or normal or ‘real’ kind, while those of neighboring families were ‘not real fish-knives’ at all.”

From a Catholic anthropology perspective, we may say that a) the special bonds of immediate and extended family, friends and neighbors, and other forms of kinship are natural and proper; b) anxiety about the unfamiliar is inevitable for fallen creatures in a fallen world; and c) biased attitudes toward those who are different are a very common, even ubiquitous result of the disordering effects of concupiscence. This kind of preference for the familiar over the unfamiliar is not racism, nor is every form of it unhealthy or unjust. It is, though, a contributing element to many unjust forms of bias, including racism.

Intergroup bias

The spontaneous individual tendency to prefer the familiar to the unfamiliar easily and naturally leads to cultures characterized by shared preferences for “us” and our ways of doing things over “them” and “their” ways of doing things—preferences sometimes called tribalism or, more technically, in-group/out-group bias or intergroup bias.

Not all forms of intergroup bias are unhealthy or unjust. Mild, tolerant forms of tribalism can coexist with respect and mutual esteem (for example, friendly sports-team rivalries and healthy patriotism). All too easily, though, intergroup bias gives rise to perennial, ubiquitous forms of unjust bias. These include ethnocentrism and chauvinism (assuming or asserting the superiority of one’s own group or culture), stereotyping and prejudice (negative assumptions about others based on their group), and bigotry and discrimination (intolerant attitudes or actions). Such forms of bias express themselves across almost every demographic divide known to humanity: men versus women, wealthy versus poor, educated versus illiterate, urban versus rural, age versus youth, etc.

None of these perennial forms of bias is equivalent to racism as we know it, though the same tendency toward intergroup bias contributes to and manifests in racism, and racism is compounded by other forms of bias, including classism.

Colorism

Another form of bias contributing to racism is colorism: any kind of preference or bias tied to skin tone, often though not always in the form of a social preference for lighter skin. One form of colorism, male preference for women with lighter skin, is globally widespread if not universal, and appears to have existed in antiquity. For example, ancient Greek and Egyptian art typically depicted women as lighter-skinned than men. The preference for lighter skin, particularly for lighter-skinned women, seems to be at least partly rooted in its association with wealth and privilege, since less well-off people spent more time working in the sun. An early passage in the Old Testament’s Song of Songs indicates as much:

I am very dark, but comely, O daughters of Jerusalem,

like the tents of Kedar, like the curtains of Solomon.

Do not gaze at me because I am swarthy,

because the sun has scorched me.

My mother’s sons were angry with me,

they made me keeper of the vineyards;

but, my own vineyard I have not kept! (Song of Songs 1:5–6)

Whatever allegorical or theological interpretations may apply or be applied to these words, the text envisions a young woman defending her complexion to “those who would mock her for her peasant’s suntan,” as the Hebrew scholar Robert Alter put it.2 The words “dark but comely” (or “dark but desirable” in Altman’s translation) imply that darker skin was considered less desirable.

A more racially charged instance of colorism in the Old Testament appears to be at work in Numbers 12, which recounts how Moses’ siblings Miriam and Aaron spoke against Moses because of his foreign wife, a Cushite or Ethiopian, i.e., a black-skinned African. While Numbers 12 doesn’t explicitly connect the criticism with skin color, it is striking that the punishment God chooses for Miriam is turning her skin leprous—“as white as snow,” the text explicitly specifies (Numbers 12:10).

Indications of colorism also appear in a number of Hindu scriptures. The Shiva Purana relates how the dark-skinned goddess Parvati became angry when her husband Shiva (himself dark-skinned) jokingly rebuked her for her skin color, leading Parvati to resolve to lighten her skin color or cease to exist. Shiva is alarmed at having offended his wife, but Parvati will not be assuaged, pointing out that Shiva’s bias is common: “Dark complexion is hated by good men. You too disapprove of it.”

Parvati then undergoes severe penance to obtain fair complexion from Brahma. Brahma tries to explain that her exertions are unnecessary, but she is adamant: “Of what avail is this talk? I wish to get rid of my dark complexion through legitimate remedies and obtain white color.” While assuring her that her wish alone was sufficient to change her skin color, Brahma grants her request, and Parvati sheds her “outer skin,” becoming white. Whatever the attitude of the Shiva Purana toward Parvati’s efforts, her remark that “dark complexion is hated by good men” surely indicates real social attitudes existing at the time.

Examples of racially charged colorism can also be found in Islamic tradition, notably around two early Muslims: Bilal ibn Rabah, a former slave and one of Muhammad’s most loyal followers, and the more controversial, controverted figure of Abdullah ibn Saba’, said to have had an exaggerated reverence for Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law Ali.

Both Bilal ibn Rabah and Abdullah ibn Saba’ were mockingly labeled ibn al-sawda, “son of the black woman.”3 “What do I have to do with the vile, black man?” Ali is said to have remarked of his misguided disciple. In addition to his dark-skinned mother, Abdulla ibn Saba’ is said to have had a Yemeni Jewish father—both biographical details possibly invented to discredit him and the religious ideas associated with him.

But when Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, one of Muhammad’s first followers, derided Bilal ibn Rabah as “son of the black woman,” Muhammad is said to have rebuked Abu Dharr for his misguided attitude. It is interesting that in many of these examples, including the two from the Old Testament, colorism is both attested and also in some way critiqued. This suggests that while colorism may be perennial, so is the moral insight that colorism is unjust.

More to come.

A few resources for further reading:

Documents of the Catholic Church: Brothers and Sisters to Us: Pastoral Letter on Racism (U.S. bishops, 1979); For the Love of One Another (Bishops’ Committee on Black Catholics, U.S. bishops, 1989); The Church and Racism: Towards a More Fraternal Society (Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, 1998); Open Wide Our Hearts: The Enduring Call to Love Pastoral Letter Against Racism (U.S. bishops, 2018); Contribution to World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, 2021).

Catholic scholarship: Davis, Cyprian, The History of Black Catholics in the United States (Crossroad, 1990); Grimes, Katie, Fugitive Saints: Catholicism and the Politics of Slavery (Fortress Press, 2017); Massingale, Bryan N., Racial Justice and the Catholic Church (Orbis Books, 2010); Maxwell, John Francis, Slavery and the Catholic Church (Barry Rose Publishers, 1975); Swarns, Rachel L., The 272: The Families Who Were Enslaved and Sold to Build the American Catholic Church (Random House, 2023).

I also recommend Gloria Purvis’s six-part 2022 video series for Word on Fire, Racism, Human Dignity, and the Catholic Church in America, and my own 2020 interview with Catholic speaker Damon Clarke Owens for the National Catholic Register, “A Conversation About Race With Damon Clarke Owens.”

Alter, Robert, The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary, Vol. 3 – The Writings: Ketuvim (W.W. Norton & Company, 2018), Introduction (Song of Songs).

Anthony, Sean, The Caliph and the Heretic: Ibn Saba and the Origins of Shiism (Brill Academic Pub, 2011), 65, 73.