Resurrection and praying with the body

Homily for Wednesday of the Fourth Week of Lent, 2024

Note: This homily was preached at Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church in West Orange, NJ, during a Saint Joseph novena.

“The devil always sends errors into the world in pairs—pairs of opposites.”

So wrote C.S. Lewis in Mere Christianity. I think he’s onto something.

For instance, there are two mistakes that we can make as Catholic Christians thinking about our faith in relation to the beliefs of others around us. On the one hand, we may fail to recognize and appreciate how much we have in common with people of other religious persuasions and how close we are in many ways. On the other hand, we may fail to recognize and appreciate what is distinctive and unique in our own faith.

For example, belief in some kind of afterlife remains widespread in American culture, despite declining religious practice and adherence. Not necessarily belief in heaven, let alone hell or purgatory, but something after death. Among those who do believe in some kind of heaven, it’s widely thought that most or even all people go there—much as Pope Francis recently expressed the hopeful idea that hell might be empty, and as Pope Benedict XVI, in his encyclical on hope, Spe Salvi, supposed that at least the “great majority” of people remain fundamentally open to divine truth and love, even if their path to heaven involves a process, in the life to come, of purgation, of cleansing.

We can appreciate this sense shared by many non-Catholics that death is not the end, along with (in my opinion at least) the shared hope that eternal happiness may be far more widely available than has often been thought in Christian history. On the other hand, for too many Catholics, generic ideas about “life after death” and even “heaven” have eclipsed the distinctively Christian hope at the heart of today’s Gospel. Hope that is inseparable, first, from faith in Jesus himself, and, second, from the hope inherited from our Jewish brothers and sisters regarding resurrection of the body—a hope that, for Jesus’ followers, took on a radically new significance on the third day after Jesus’ death by crucifixion.

Amen, amen, I say to you, the hour is coming and is now here when the dead will hear the voice of the Son of God, and those who hear will live.

Now these words read as spiritual metaphor: Those who are dead in sin, spiritually dead, will hear Jesus’ voice and receive spiritual life. But then Jesus goes on to double down in more realistic language:

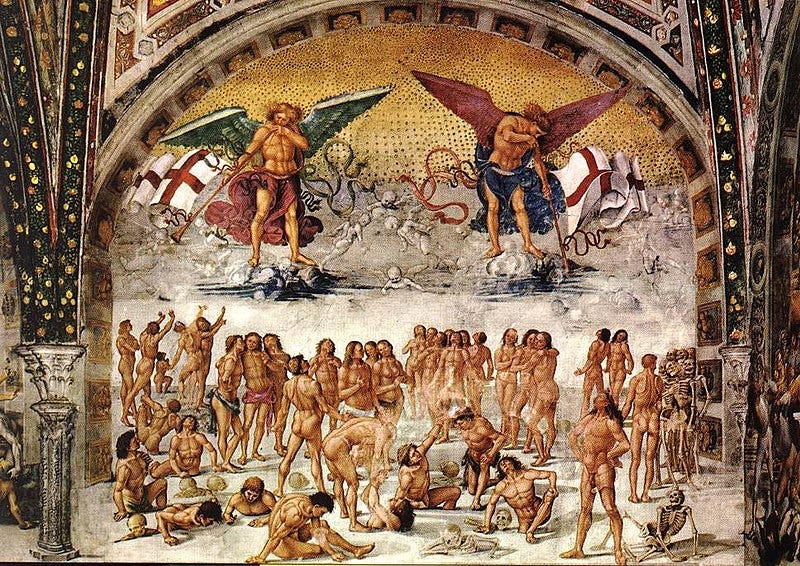

Do not be amazed at this, because the hour is coming [notice he doesn’t add “and is now here”] in which all who are in the tombs will hear his voice and will come out, those who have done good deeds to the resurrection of life, but those who have done wicked deeds to the resurrection of condemnation.

Here Jesus reveals the ultimate reality from which the metaphor is drawn. It’s a lot like how in the next chapter, John 6, Jesus first calls himself “the bread that came down from heaven”—a spiritual metaphor; the Son of God in heaven is not bread, did not come down as bread, and was not incarnate as bread—but then he goes on to double down in more realistic language: “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life…My flesh is real food, and my blood is real drink.” The same move from spiritual metaphor to bodily reality—and for the same reason: Jesus came in the flesh to redeem our bodies as well as our souls.

Too many Catholics have a woefully truncated understanding of Catholic eschatology—that is, of Church teaching regarding the life to come. We often hear that Jesus died to “save our souls” and that our hope is that when we die “our souls go to heaven.” Which is not so much wrong as painfully incomplete—like thinking that marriage is the wedding reception! Like, you get married and then you go to this party where there’s music and cake and that’s what marriage is! (But wait…there’s more!)

Jesus came in the flesh to redeem our bodies as well as our souls. Through his birth from the body of the Virgin Mary. Through his bodily life on this planet, his daily work alongside Saint Joseph. Through his immersion in water at the hand of his cousin John the Baptist, the ritual meal he shared with his disciples before his arrest, and above all through the wood of the cross and the empty tomb, his bodily death and his bodily triumph over death. Through the sacraments that we receive in our bodies: the waters of our baptism, the true food and true drink offered to us in the Mass. It all culminates for us in our resurrection on the last day—or, if we choose to reject God’s gift, what Jesus calls the resurrection of condemnation. Body and soul together share in our relationship with God, or our refusal of it, in this life and the next.

In Christian life, the corporeal and material sphere cannot be disregarded, because in Jesus Christ it became the way of salvation. We could say that we should pray with the body too: the body enters into prayer.

We should pray with the body too: the body enters into prayer. This is a crucial insight, never more so than in 2024—“the Year of Prayer,” according to Pope Francis, in preparation for the coming Jubilee holy year of 2025. The Holy Father has asked us to devote this year, 2024, to “a great ‘symphony’ of prayer.” How can we do this? How can our bodies enter into a “great symphony of prayer” in 2024?

I want to briefly highlight three essential ways of praying “with the body too”: the liturgical way, the Lenten way, and the private way. These are not alternatives; we need all three.

First, we need to enter bodily into the liturgy, the celebration of the sacred mysteries. To bow and kneel and stand together; to hear with our ears and respond with our voices. To see with our eyes the body of Christ offered for us on the altar, and of course to taste, to receive into our bodies. (By the way, at the elevation, when the celebrant lifts up the host and the chalice, many people bow their heads and close their eyes—but the rubrics literally say the priest “shows” the host and the chalice “to the people.” We’re meant to see at that moment!) Of course without interior faith and devotion, these bodily actions by themselves are not prayer. But this doesn’t mean that interior prayer is all that matters, and not what you do with your body! Remember, the devil sends errors in pairs. Body and soul together pray in the liturgy when we seek to take part with our whole being.

Second, especially in Lent, prayer is joined to fasting and almsgiving. We seek to restrain bodily appetites while at the same time caring for the bodily needs of others. In a spirit of prayer—or else fasting is just dieting and almsgiving is just philanthropy. But if we seek God, fasting and almsgiving become part of our prayer.

Finally, daily private prayer is essential to our relationship with God, and our body is part of that as well. Like Jesus going off to deserted regions to pray, we need to seek out solitude and silence on a daily basis. Here again two things are true. We can pray while driving to the store or doing household chores—and we should—but it’s time set aside for God that anchors our prayer life. Time set aside to stop doing things, to sit down or kneel and give God your whole attention, minimizing external distractions (phones turned off or in “do not disturb” mode).

If we seek to pray “with the body too” in these three ways—the liturgical way, the Lenten way, and the private way—then we can begin to realize the Apostle Paul’s exhortation to “pray without ceasing” (1 Thessalonians 5:17) and, “whether we eat or drink, or whatever we do, to do all things to the glory of God” (cf. 1 Corinthians 10:31). Then we can work alongside Saint Joseph in making our daily labors part of our prayer.

Lord, teach us to pray “with the body too.” Amen.

I love your homily, and was delightfully surprised by the quote from Pope Benedict’s encyclical. A statement like that, coming from one so very conservative, brings me joy!