No one Gospel gives us all seven of the “last words of Christ” on the cross. In the Passion from John’s Gospel, just proclaimed, we get three: “Woman, behold your Son”; “I thirst”; “It is finished.” Perhaps we still have echoing in our ears, from Palm Sunday, the most haunting of the seven last words, both from Mark’s Gospel and from the Responsorial Psalm: “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” (or “forsaken me?”).

That’s Psalm 22, but the spirit of the lament runs through any number of psalms. “How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever? How long will you hide your face from me?” (Psalm 13:1) “Lord, where is your steadfast love of old?” (Psalm 89:49) “My tears have been my food day and night … As with a deadly wound in my body, my adversaries taunt me, while they say to me continually, ‘Where is your God?’”

Where is God? Where is God when we suffer? When people we love are in pain? When the world makes no sense? When we cry out in need and help is not forthcoming? The theologian and the apologist leap to answer these questions, rightly enough—but we don’t need answers, we need help. We need God. Where is he when we need him most?

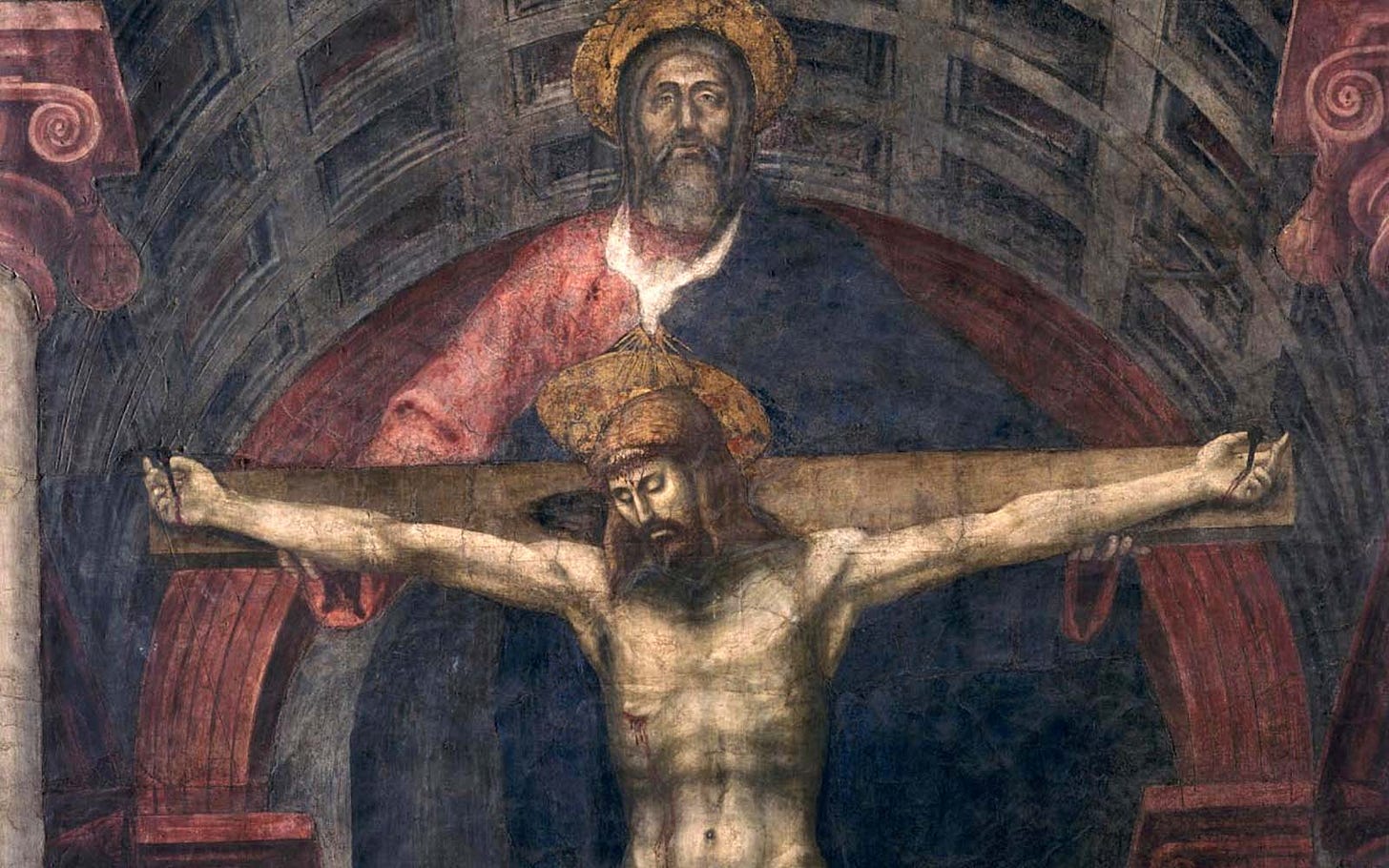

On this day, Good Friday, nailed to the wood of the Cross, our Lord Jesus makes this eminently human question his own. He shares not only our suffering but our sense of cosmic aloneness. In the daring words of the Catholic writer G.K. Chesterton: “When the world shook and the sun was wiped out of heaven, it was not at the crucifixion, but at the cry from the cross: the cry which confessed that God was forsaken of God.…” a cry at which “God seemed for an instant to be an atheist.”

Perhaps Chesterton overstates his point. If Jesus does make our sense of abandonment his own, he does so—like the psalmists—in the form of a prayer. The question is not “Where is God?” (or “Where is your God?”) but “God, where are you?” Even if we struggle with this question, if we do it this way, in prayer to God, that’s where we find the crucified Lord alongside us in our suffering and abandonment.

Which is to say, we are not abandoned. In making our question his own, Jesus provides the beginnings of an answer. Where is God when we suffer? Suffering with us. When our loved ones are in pain, Jesus suffers with them and with us. Jesus is crucified in Ukraine, in Gaza, in Sudan. He suffers in hospitals, in psych wards, in rehab, and in your room and mine when life is overwhelming.

In and through this divine solidarity, we believe, God is accomplishing something called redemption: the overcoming of evil, the transfiguration of suffering, the swallowing up of death itself. But it begins with divine solidarity: Emmanuel, God with us, in our suffering. God is never closer to us than when he feels most absent. And the prayer that seems to stop at the ceiling and go unheard in heaven is the prayer that is dearest to the Father’s heart.